Keeping with those beloved arcade values.

The strangest thing was happening: During these, the early months of 1989, my NES collection was growing rapidly, yet I, the owner of the console, could hardly claim to be playing a significant role in the expansion effort; if anything, I'd purchased maybe one or two games in the period spanning from January to May. Instead, it continued to be that my brother, James, was the main driver of this expansion.

That James was showing himself to be far more adventurous than me wasn't out of the ordinary, no; really, that's how it had always been. Rather, I found his behavior to be odd because concurrently he wasn't displaying even the faintest perceivable interest in the console, and I couldn't recall a single instance where he had sampled an NES game for more than a few minutes. Furthermore, never once did I get any sense that he was familiar with or cared at all about the scene. Yet there he was actively broadening my game library and constantly introducing me to new games, most of which fit into the categories of (a) those that were largely unfamiliar to me and (b) those I'd have been predisposed to dismiss on sight. And never did he provide explanation for why he was buying these games or why he thought I'd be interested in playing them.

Weird, huh?

Honestly, though, I had no objection to what he was doing. In fact, I was rather happy about it. Having access to a large pool of NES games made me feel as though I was now highly active in the scene--that I was now a legitimate member of a longstanding club!

These games represented the first wave; they were the ones I'd forever associate with my brother and particularly with his buying sprees, which brought into my life so many of the favorites that I might have otherwise completely missed--so many of those that I fondly remember for how they contributed to my development as a gaming enthusiast.

I tell you, man: Thank goodness James was there to fill in my blind spots.

The first of these new arrivals was a little game called Trojan.

Naturally I'd never heard or read anything about it. Though, as I was a student of classical mythology, the title, itself, was instantly familiar to me. It suggested something obvious: "A game called 'Trojan,'" I immediately thought, "probably entails subject-matter related to ancient Greece and specifically the Trojan War, in which Greece and Troy engaged in a ten-year conflict!" However, my faith in that theory was promptly shot to pieces as I focused in on the game's box cover, whose cyberpunk-style artwork indicated nothing of the sort; rather, it featured a conspicuous rendering of two futuristic-looking figures. The one in the foreground (the protagonist, I assumed) was a crazy-eyed punker who could be seen brandishing a gleaming sword and a well-worn shield, and he had apparently crashed through a wall en route to confronting a bald axe-wielding barbarian. Standing behind the protagonist--surveying the scene--was a frightening figure whose menacing red eyes coldly stared out from a roughly hewn metal helmet ("That guy resembles Shredder," I famously noted).

I couldn't recall seeing anything like it. It had always been that video-game box art was binary in nature, the depictions normally either cartoony or realistic-looking, with blown-up pixel art considered to be the most radical departure. But Trojan's visuals clearly stood outside of that paradigm. Gauging them, I could only describe its renderings as "completely abstract."

"What could this game be?" I wondered. Certainly it wasn't related to any Greek mythology I'd ever read about. There were no classical-looking Trojan warriors (those donned in Corinthian helmets, red capes and brown tunics) or Spartans to be found on this cover.

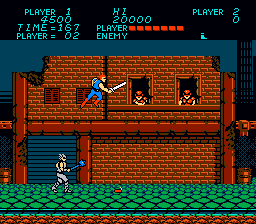

So I popped it in the NES and gave it a look. And, well, it was immediately evident to me that the in-game visuals, too, bore little resemblance to their supposed inspiration. There were no coliseums, pillared temples or other products of ancient-Greek architecture to be seen; rather, Trojan's action was situated in what appeared to be a modern-world setting (a greatly deteriorated modern world, at least). "Really, this isn't anything I haven't seen before," I thought, initially, as I watched the demo play. "Why would they give such a loaded name to a game that's observably standard in presentation?"

Still, I wasn't too disappointed. I was, after all, a big fan of arcade-style action games--particularly those that featured fast movement and interesting combat mechanics--and Trojan's demo hinted that it was certainly of that variety.

And indeed it was: In the early moments, Trojan showed itself to feature briskly paced, satisfying action. I took to it instantly. Though, I did have a little trouble adapting to its controls, which were unique if not somewhat quirky. For one, this was the first side-scrolling action game I played where both the A and B buttons had action commands assigned to them; one prompted the hero to swing his sword, and the other prompted him to hold out his shield (I thought it was really cool how you could apply directional input to the latter and in addition hold the shield vertically or diagonally upward!). The problem was that I'd often confuse the two when the action grew hectic. Also, as a consequence of this design choice, the developers had little option but to assign jumping to up on the d-pad--a scheme I almost never found desirable. As a Commodore 64 player, I had years of experience in controlling jumps in this manner, yes, but I couldn't say that I'd ever become fully comfortable with doing so; but since I had every intention on sticking with Trojan, which was proving to be a lot of fun, I put in every effort to adapt.

Considering all the trouble I used to have with those types of multi-input games, I think of it as kind of a miracle that I became so well-acclimated to Trojan's controls in such a short period of time. Could it have been, I wonder, that I was evolving as a player? Or was it that Trojan's press-up-to-jump mechanic was simply superior to Bruce Lee, Zorro and Trolls & Tribulations'--the first time they were done "correctly"? I don't know; for all of the ruminating I've done over the matter, I've never been able to come up with an explanation with which I feel comfortable. I just settle upon the idea of it being "a combination of both suggestions."

Trojan, I'd soon discover, wasn't simply a "standard action game," which I initially suspected it to be. It had some welcome surprises--a couple of notably cool differentiating features. There was, for instance, the disarmed-mode mechanic, which would activate whenever the hero (to whom I always referred as "Trojan") used his shield to block a knife-tossing enemy's secondary hatchet projectile; the hatchet's overpowering force would knock away the hero's weapons and leave him unarmed, forcing him to rely on Kung Fu Master-style martial arts (mainly upright, crouching and flying varieties of punches and kicks) until he could locate and retrieve his weapons! In reality, the time spent in disarmed mode was pretty short-lived, since the weapons would reappear once you advanced a mere one or two screens, but still those were important seconds; they're what helped to establish that Trojan's action had another dimension to it--a second, more-challenging mode of play that was baked into the main game. Also, it was always fun to kick knights in the face!

And then there were the boss battles, which required that I apply actual strategy in place of my usual tactic of "get up in the boss' face and flail maniacally." In contrast to those experienced in Ninja Gaiden, Double Dragon and the aforementioned Kung Fu Master, Trojan's boss battles harshly punished such impulsive behavior; it demanded, instead, that players read an opponent's movement, work around his defenses, and find available openings. This was off-putting to me at first, since I didn't immediately understand what the designers were going for and kept getting destroyed in seconds, but once I caught on and discovered how to work within the system--to show patience and employ evade-and-counter tactics--I found this mode of combat to be genuinely rewarding. So much of the fun I had in my earliest experiences with the game was based around my interactions with these bosses and figuring out how to effectively assail them.

Before playing it, I would never have guessed that Trojan, which as far as I knew held no relevance or distinction, would be the game successfully sell me on the idea strategy-based combat. Funny that.

Trojan's quickly became some of my favorite boss characters. I liked everything about them: how they looked, how they animated, and how they performed. They seemed so wonderfully expressive to me, their movements and facial features giving the appearance that they were reveling in their evil actions (and you like to see the bad guys take joy in their work--you know?). The only problem was that I didn't know any of their names, since I lost the manual before I had the chance to read it. I didn't learn of their names until I saw the game's credit's sequence wherein each boss was identified as it took a curtain call (the manual, which I found a few months later, identified some of them differently, the names and descriptions so generic that it was clear that the localization team never actually played the game). In the interim, my friends and I made up our own names for them. We called Goblin "Jack," for instance, and determined that the Mamushis should be called "The Great Goudini Brothers."

Don't ask, man. I have no clue.

But what really grabbed me was Trojan's graphical presentation. I simply loved how it went about depicting its world. In particular, I was enamored with the background visuals in its first two city levels. It was always that my eyes were drawn to the buildings that populated their backgrounds--to the distant cityscape whose formation resembled the one belonging to the aesthetically pleasing Manhattan backdrop as I observed it whenever I was riding with my father along the highway at dawn. I'd had a fondness for the depiction of cityscapes for as long as I could remember, and this one was an instant favorite.

And those buildings became an even greater source of interest once I learned about the game's post-apocalyptic nature. That's when their presence truly began to send my imagination into overdrive--when I felt inspired to wonder about the state of those buildings, which I'd imagined had been abandoned for decades. "When was the last time anyone visited one of these buildings?" I'd wonder as I gazed at them. "And how desperate and lonely would it be for any survivors who were still hiding out or taking refuge in one those skyscrapers?"

I mean, sure--those buildings were nothing more than a few simple, crudely drawn rectangles plastered across a single-color dark-blue background, but to me they were the most valuable of renderings; they allowed for me to add some of my own personal context--to form a connection with the game through my interpreting of its world. To an 11-year-old, that was the power of 8-bit games: They could make even the most rudimentary visuals seem wondrous.

In closer view were the battered, dilapidated structures that served as a vestige of a once-active civilization. There, along the streets, stood shops, garages and tenements that bore deep wounds but still found function, their upper-level's paneless windows now a perfect vantage point for the enemy force's dynamite-tossing baddies. I became enchanted by these buildings--by the setting they created--the moment I laid eyes on them. Immediately they produced an air of relatability; as I surveyed them, I was reminded of all of the nostalgically aged storefronts and tenements I'd see whenever I'd walk the streets of Brooklyn. Their presence imbued Trojan with a sense of atmosphere that inspired me to think about a game in a way I never had before. In ruminating about this opening scene, I'd often wonder about what it would be like if I could somehow transport myself into Trojan's world and see it in person--see if it truly was a match for the Brooklyn streets as I viewed them from the side opposite.

The second level featured altogether-similar background imagery, yes, but its opening portion included a unique visual that I'd never forget--one that would become the most memorable of my youth: a fenced-in backlot that served as the final resting place for a broken-down Volkswagen Beetle. It was such a remarkably faithful rendering (for an 8-bit game) that I couldn't help but be fascinated by it. And once I became aware that Trojan's was a post-apocalyptic setting, I became further enamored with the visual because of what it now represented--how this ramshackle Beetle, alone, told the whole story of when, exactly, civilization came to an end (early 80s, judging by the car's build). I loved Trojan's approach to world-building--how its designers chose to set their game in the ravaged-yet-mostly-preserved 80s-style urban environs rather than the otherwise-standard, highly cliched desert wastelands and metallic ruins. You know--what was common for video games.

Though, once I advanced to the second pair of levels (each level was but a single "block" in a two-part "stage"), it became apparent to me that Trojan had no intention of sticking to a "ravaged city" theme. Stage 2's mountainy environments told me that ensuing levels would seek contrast, which I found to be disappointing, since I was eager to see how they'd expand upon the theme--to see what other type of reminiscent urban settings they could craft. In time, however, I came to appreciate the variance in setting; the following levels lacked for similarly relatable associative qualities, true, but I couldn't deny that their visuals, too, were able to speak to me, albeit in different ways. These spaces--the bleak, inhospitable mountain ranges, sewer systems and stone fortresses--were packed with the types of graphical touches that really got my imagination stirring; as I'd inspect them, I'd think about all of the potential ways in which these facilities could have been repurposed by the mutant hordes and how their kind might have operated within them. "What types of creatures would come to inhabit these spaces if humans ever decided to dump this 'Earth' place in favor of something better?" I'd wonder. "And how would they function?"

But most of that came later on, when we grew competent enough to advance far into the game. In our earliest experiences, wherein Trojan was looking to be one of the most monstrously difficult action games we'd ever played, we spent most of our time traversing and re-traversing the first couple of stages. It was here where most of our lasting memories of the game were recorded; it was the sights and sounds therein that became our favorites.

In particular, we were always sure to drop down into the optional sewer areas, whose oddly mysterious aura we couldn't resist. There were two reasons they resonated with us: The first was that they contained concealed items and power-ups (like health-replenishing hearts, strength and speed boosters, and points bonuses awarded for releasing rats), uncovering which required a strange method of jumping all about and randomly swinging the sword. It was such a weird thing for a game to demand; recalling our separate histories, none of us could think of any other game wherein you had to strike seemingly-purely-decoratory background tiles in order to reveal hidden items.

Of greater impact were their visual and aural qualities. The sewers' memorably mysterious atmosphere was generated mostly by their backgrounds--by their brickwork, whose eerily luminescent green hue on its own suggested that these neglected conduits were actually still teeming with life, the majority of it probably unseen--and their ominous-sounding musical theme, which worked to evoke feelings of unease and create the sense that evil entities would soon reveal themselves and pounce. I mean, we knew that actually nothing was going to happen--that once the mini-boss had been dispatched we'd be able to move about unmolested--but still the atmosphere's conveyance was powerful enough to fill our heads with the idea there were twisted creatures lurking somewhere between those cracks.

That's how Trojan went about informing the player about the state of its world: It would populate its backgrounds and textures with intriguing visual indicators and therein invite him or her to wonder about how the environment in question was being utilized by its new masters--about how they functioned now that they'd been repurposed. And I was the type to spend hours filling in the blanks: Whenever I'd gaze upon or think about, say, the unrecognizable machinery in the enemy's vertical bases, I'd imagine scenes wherein those who survived the fallout--those who became deranged mutants--maniacally toiled about their claimed territory as they installed all new types of technologically advanced apparatuses (thermal generators, multi-paneled hatches, man-sized chutes, motion-activated lifts, and other sci-fi-lookin' mechanisms) invented for the express purpose of exhibiting their superiority to the former occupants, the lowly humans. Yet the game also communicated that the rebuilding effort was still in a very early phase--that the emerging civilization at this point was still primal in nature--by arming its foes with comparatively primitive weapons like clubs, swords, crossbows and dynamite.

This made for a fascinating dichotomy, I thought. The old was being used to defend the new. For the enemy, victory via the ancient sword meant eventual domination via the city-leveling laser cannon.

I just really liked thinking about Trojan's world, man. It wasn't a place I'd ever want to live in, no, but it was sure fun to wonder about!

It helped that the soundtrack was pitch-perfect. As you descended ever-deeper into enemy territory--into the depths of Hell, itself--the music would gradually shed any heroic-sounding strains and continue to grow more urgent and menacing; it would endeavor to further color your perception of its increasingly dire set pieces and therein guide your emotions. So by the time you hit the final stretch, the oppressive halls of Achilles' catacomb fortress, you'd really feel as though pressure was bearing down on you--feel that some evil force would promptly engulf you if you stopped pushing forward for even a single second.

Trojan's music did a great job of conveying to you both the heroic and desperate aspects of its hero's journey. It was fitting for a dystopic world of struggling humans and mutant aggressors. That's why Trojan's was one of my favorite NES soundtracks. I still think highly of it. Seriously--I'd put it in the top 20. If the game weren't so overlooked, there would probably be many more people expressing the same sentiment.

Furthermore, Trojan's soundtrack is especially relevant to me because it introduced me to what I'd come to know affectionately as "Capcom music." From then on, thanks to Trojan's power of implantation, I could instinctually tell that I was playing a Capcom game simply by gauging the music's style of instrumentation; I could positively identify a game as a Capcom property merely by listening to a single stage theme. This was Trojan's most formative contribution.

Indeed Trojan's soundtrack prepared me for what was to come and insofar provided me my first true access to Capcom's unmistakable, legendary catalog of musical scores. This was a scrumptious first taste of it!

Above all, Trojan was just plain fun to play! What it offered was exactly what I was looking for in an arcade-style game: fast-moving, satisfying action; a spirit of inventiveness; and manageable length (if you know what you're doing, you can plow through it in about ten minutes). At that point, in early 1989, it was the first time I played an NES game and thought to myself, "This reminds me of an actual arcade game!" Trojan's were true arcade values.

There was an obvious reason for that, of course, though I wouldn't become of aware of it--or of Trojan's true origin--until sever years later, when it came to my attention (probably via a Gamefaqs search) that Trojan wasn't an NES original but rather a port of a coin-op game of the same name! To my great surprise, I learned that Trojan actually debuted in arcades way back in 1986, back when Capcom was but an upstart. I was especially amazed that I'd somehow never heard of it. I mean, as an arcade-goer, I was quite familiar with the company's earliest works--with well-known titles like 1942, Section Z, Commando and Ghosts 'n Goblins--yet I had no knowledge of the concurrently appearing Trojan (nor did my brother or any of his closest friends), which somehow managed to completely slip under my radar. Thinking back on those early days, I couldn't even recall encountering a cabinet bearing that name. Apparently, according to the reviews I was reading, it was of middling quality and not really worth arcade-goers' time, which I was sad to learn; though, I still wished that I had a gotten a chance to play it at least once, if not simply to have a grasp on its "historical" significance.

Still, as far as I was concerned, Trojan would always be more closely associated with the NES. For certain, it would recognize it as being way more foundational to Nintendo's console than to the 1986 arcade scene.

Truly Trojan was one of our favorites. In those early years of my NES ownership, my friends and I would seize upon any available opportunity to pop it in and give it a quick run-through--maybe set a goal of earning a better completion time or clearing the game without suffering a single death. That's how we'd fill those 15- to 20-minute periods when we were waiting for the Chinese food to arrive or looking to fill time leading up to our scheduled trip to the batting cages. That was Trojan's role--one it played commendably; it could always be counted upon to fill a gap and therein provide us precious minutes-worth of fun and entertainment.

In the recent months, I've been focusing my attention on the arcade original, which is, well ... certainly something. There are pretty striking differences: For one, it's brutally tough--more so than even the conventionally difficult arcade game. Hell--it makes the NES version look like a Sesame Street game. Two specific technical issues render it downright unfair: (1) There are absolutely no invincibility frames, so the aggressive enemies, which are constantly sandwiching you, can rapidly pound you into submission before you can even begin the process of counteracting. And (2), for reasons I'm not knowledgeable enough to explain, damage-values aren't nailed down, which means that enemy attacks inflict seemingly-arbitrary damage; so a club strike can sometimes clear away one health unit, other times two or three, and occasionally all eight at once. If you can imagine a scenario wherein you pump a quarter into the arcade machine and lose all three of your lives in a span of about ten seconds, then, well, you will have pretty much formed a solid conceptualization of the Trojan experience.

Its other troublesome issues include unforgiving checkpoints, the placement of which often demands that you continue to re-traverse some of the most monstrously difficult stage portions, and a lack of hitbox consistency that works to render the game's strategy-based combat system largely pointless; knowing the bosses' tendencies and vulnerabilities means nothing when half the time your well-timed, calculated strikes fail to even register. The latter issue is especially inconvenient when you're tasked with taking down two bosses at the same time; really, doing so is a near-impossibility when the nightmarishly unassailable Iron Arm is either one or both of them. Don't be misled by your experiences with the NES game, in which the process of reading bosses and counterattacking is easy to learn: If while playing arcade Trojan you hope to reliably take down bosses, you'll have to possess godlike skill--absolute-top-level reaction time and mashing ability. For those not so gifted, Trojan will likely prove itself to be unbeatable, its offer of unlimited continues nothing more than an empty gesture.

Oh, and it's an 80s-era Capcom arcade game, so naturally you'll have to run through it twice if you want to see the true ending. As if that's something anyone would want to do.

Sure--it's a lot prettier than the NES version, and its controls feel much smoother, but it finds itself lacking in the most important area: fun factor. When I play it, I rarely find myself having a good time; more often than not, arcade Trojan's action shows itself to be an exercise in extreme frustration.

It's no wonder I never saw it in arcades. I mean, I can't imagine that many patrons were lining up to spend dollars at a time to play an ostensibly spiteful game that appeared to making up its rules on the fly. (To be fair, though, the game's rough, unpolished nature probably speaks more of Capcom's programmers still being rather young and inexperienced, so I don't want to go as far as to imply that they were trying to cheat people out of their money.)

Having now played both versions, I can state definitively that Trojan's is another case where a home-console port is superior to an arcade original. In achieving that status, the NES version joins a select group of distinguished, highly preferred home-console conversions--of exemplars like Rygar, Ninja Gaiden and Bionic Commando. Also, it shows the gaming world what arcade Trojan could have been had its creators been able to iron out the technical kinks--that had it been polished up a bit, it might have stuck around longer and earned itself the rank of "arcade classic." It speaks of a better fate for the Trojan IP.

Too bad it didn't work out.

Still, discussions of quality aside, I've always loved the idea of two different versions of a game existing--of there being two different expressions of a designer's vision. I've always enjoyed comparing the separate versions of games and discovering where one or the other has a clear advantage. Where Trojan is concerned, there are a couple of noteworthy differences: I find the arcade version to be more visually engrossing with its finely drawn city- and mountainscapes, scrolling backgrounds, and multitude of distinctly rendered buildings (each shop has its own name and set of displays!) and structures. It features smoother controls, as mentioned, and its action moves at a brisker pace. Its music has that classic metallic quality that functions so well to distinguish it as a product of those beloved arcades--of an era I adored so much. And it's a fully formed version of the game; that is, its system board lacks the storage limits that would require, say, its ninth and tenth levels to be condensed into one.

The NES version is more technically sound (save for some largely inconsequential screen glitching) and certainly more playable. Its music, I feel, is superior in terms of instrumentation and tone, its darker edge doing more to stir emotions and inspire the type of mental renderings that are more appropriately descriptive of a world that finds itself in a desperate state. Despite its missing an entire level, this version still feels more fleshed out thanks to addition of the sewer areas into which you can descend and flail around to procure exclusive power-ups, like the boots that allow you to jump three-times higher and therein effectively assail perched enemies (in the arcade version, you can only do this by utilizing the sporadically appearing "jump" pads). And it features some other significant additions, like the exclusive catacomb boss King Shriek, whose inclusion helps to pad out the boss roster and, if only marginally so, reduce the feeling of repetition as generated by the game's repeated recycling of bosses; also, his wall-shattering breakout animation, which entails dislodged bricks being thrown all over the place, is something to behold. I appreciate, too, the manner in which the designers broke off the Achilles battle into its own self-contained stage--how they meant for the newly implemented introductory sequence and the isolated setting to provide this fight a greater sense of culmination.

Also of some relevance is the exclusive one-on-one combat mode, which represents Capcom's first foray into the fighting-game genre, which it would later revolutionize. Here, in its infancy, it functions as a curiosity--as a merely "interesting" extra that's worth checking out once or twice. Back in the day, we'd play it occasionally--usually for a couple of minutes--and extract from it what we could; at the least, we all enjoyed listening to the cool battle theme as we hyperactively flailed about.

The NES version wins hands down, of course, and remains the one to which I'll continue to default. But that's not to say that the arcade version has no place in my life. No--I find value in it. I recognize that it has some endearing qualities. That's why I continue to keep it near: I want it to remain close because (a) it reminds me of how much I love old arcade games--how they look and sound--and (b) its markedly ambitious elements (those mentioned above) so strongly resonate with me.

But that NES version, man--that's the one I'll always adore most. How can I not? It is, after all, a game around which so many cherished gaming memories have been formed. It's a game whose world inspires me to imagine. It's a game that has provided past and present versions of me a reliably entertaining, short-but-sweet action experience whenever there's been a desire for one.

And that's how I feel about Trojan, the humble little NES game that came out of nowhere and provided me my first truly tantalizing glimpse into the world of Capcom. Call it my formal introduction to the company that would soon win over my soul--to the company that would soon become a burgeoning force in the industry and eventually a king. I'm happy to have been there during run-up--to have witnessed the development phase--when games like Trojan were laying down the foundation. It's part of how we're connected; it's the process through which Capcom and I grew up together.

Now, I get that Trojan isn't exactly highly regarded by the gaming community. Whenever its name comes up in conversation (either on podcasts or message boards), it's often dismissed as being "mediocre" or "forgettable." And I admit that it has a number of flaws: There are a lot of noticeable rendering issues (screen flashes and visual glitches). It continuously recycles the same six bosses. It's missing an entire level, and the compensatory "merged stage" is largely devoid of action. And a somewhat-embarrassing design flaw rears its head whenever it so happens that all of the currently present minor enemies spawned from the screen's left side; since trailing enemies (specifically the omnipresent club-wielding knights) are unable to make contact with an in-motion Trojan, any instance of double-backspawning will allow for you to freely cruise through the rest of the level.

But I maintain that none of this points to Trojan being mediocre. What it says is that people don't give it a fair chance because from the outside it appears to be a lesser title. Really, it isn't; it's actually pretty solid.

Quite simply, Trojan is what it is: an early NES product that embodies the spirit of mid-80s console gaming and wonderfully demonstrates the type of simple fun it had to offer. That's to say that Trojan's is a true 8-bit arcade-style experience.

Certainly it's an essential piece of my gaming library. I return to it frequently because it serves me on multiple fronts: It's fun to look at and listen to. Its action always satisfies my itch. And it never fails to remind me of good times with friends.

For those reasons, Trojan will remain in my heart forever.

Trojan is a game I've seen in advertisements and second-hand shops my entire life, but I didn't even know what the gameplay looked liked until very recently. Nobody ever talks about this game.

ReplyDeleteFortunately, it's quite easy to find. Looks like I'll have to become better acquainted.