How Mario's miniaturized adventure helped to sell me on the Game Boy and make it a permanent fixture in my life.

You could say that I was a kid who had very narrow tastes. I only watched sitcoms and action-adventure series like The A-Team, Airwolf and V. I only listened to popular songs. I only read books about monsters. When it came to cuisine, I never ventured beyond pizza and Chinese food. And whenever we'd go to a diner, I'd always order the same damn things: a bowl of soup with either a bacon burger or chicken in the basket.

I just didn't like taking risks. So I would always play it safe and thus dismiss anything that was outside my interests.

It was the same way with video games: I wasn't keen on playing any game that didn't fit into one of my three favorite genres: action, platforming or puzzle. I knew what I liked and was content to subsist on such forever. As far as I was concerned, everything else could pound sand.

One of the best examples of my stupidly unadventurous practices was the way with which I'd engage with any issue of Nintendo Power. In every instance, I'd skim through its 116-plus pages and do so only with the intent of locating game titles and subjects with which I was already familiar. And that's all I'd read about. I'd basically ignore the other 75% of the magazine's content and be done with it in minutes.

You have to admit, dear reader: That was a really dumb way for me to use a product for which I was paying $15 a year.

And my willing obliviousness was one of the big reasons why I wound up disregarding so many great games and so many amazing treasures like the original Game Boy, of which I was barely aware despite its being plastered all over the magazine's pages for more than a year!

In those days, that's how I treated the Game Boy: I didn't acknowledge images of it, I didn't read about it, and I certainly never thought about it. Really, I had absolutely no interest in Nintendo's new "portable game system." Based on what little I'd gleaned about the Game Boy, I'd decided that there was no place in my home for such a device! "I don't need some super-small, battery-powered, back-and-white-screened, dumbed-down NES!" I told myself.

"Hmph," I'd say, dismissively, anytime I'd see an image of the Game Boy. I'd just wave it away and then quickly flip over to a Double Dragon preview or the Classified Information section.

So, as you could imagine, I was a feeling a bit apathetic when I woke up on Christmas Day of 1990 and found a Game Boy sitting under our tree. I knew that I never asked for a Game Boy, so all I could do was wonder why my parents thought to buy me one. I wondered, also, how they even came to know of such a thing as Game Boy (of course, it was still a hot toy at the time, and holiday-focused parents were always aware of the items that were currently popular with the kids).

Now, you might think that my facial expression conveyed something along the lines of "I didn't want this thing!", but it actually didn't. Rather, it was more along the lines of a hesitant "I'm not so sure about this one, guys." They didn't read anything into it because, really, looking tentative was the norm for me; it's about what they expected.

I wasn't mad or even annoyed that I got a toy I didn't ask for, no. I was just kinda indifferent. My first thought was, "Well, I guess I got this thing now."

Yet in the following minutes, my feelings rapidly evolved: As I was engaging in the process of opening the Game Boy's box and removing it from its plastic wrapping, my feelings of apathy started to fade away, and soon feelings of excitement started to creep in. And when I held the Game Boy in my hands for the very first time, a feeling of elation washed over me, and suddenly I realized just how cool this "console-in-your-pocket" concept truly was.

In that moment, I knew that I'd made a serious mistake in disregarding the Game Boy. I was completely wrong. I did need this device in my life. It was the coolest thing ever, and I was thrilled to own it.

What made this whole event even more exciting was the generous number of games I got in addition. There were four in all: the humble pack-in game, Tetris; The Amazing Spider-Man; Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Fall of the Foot Clan; and another little game you might have heard of.

Its name was Super Mario Land.

After all of the gift-giving was completed and my parents headed upstairs to prepare for the day-long activities, I decided to try out my new Game Boy right there in our living room. I remember that room fondly: It had a mirror wall, blue carpeting, a white-colored veneer-stone-faced fireplace, a piano, and an azure-colored corner couch that wrapped around and furnished its entire northeast portion. I recall how calming and comforting it was (truly I have great nostalgia for my childhood abode and the unique atmosphere that each room was able to create).

Though, I had a little trouble seeing the Game Boy's screen because the living room was the only room that didn't have ceiling lights, and its only source of illumination was the large window on the room's opposite side; the problem was that the entire window was shaded, so the only thing the room received from it was faint refracted sunlight--the type that obviously wasn't radiant enough to make the Game Boy's screen more visible. So what I had to do, instead, was move from one part of the couch to another and keep finding the areas whose faint lighting was, at the time, most adequate.

Of course, I immediately gravitated toward Super Mario Land because it was the most familiar property (and a platformer!). I have to say, though, that I was a little confused by what its box art depicted. The image had Mario fleeing from a whole bunch of strange, un-Super Mario Bros.-like characters: a sphinx, a robed demon, a winged rock creature, and a cat piloting a spaceship. Also, there were two other likenesses of Mario depicted on that box, and, curiously, they were piloting a plane and a submarine, respectively.

"This is a traditional Super Mario game, isn't it?" I silently questioned, with a significant amount of concern, as I examined the box's art. "It's still about breaking blocks with your head and shooting enemies with fireballs, right?"

I mean, that box gave off such a weird vibe, man--one that was very different from the type exuded by console-game box art (even the strangest ones). As I continued to examine it, I couldn't help but get the feeling that something was amiss here.

My very first session with Super Mario Land made a quick shift from comforting to completely jarring.

It started out just fine: When the title screen came into view, I saw what one would expect to see on the starting screen of a Super Mario game. It depicted Mario, our beloved hero, and Super Mario-type things like hills, clouds and even a mushroom. Thus it gave the impression that Super Mario Land was indeed a traditional Super Mario Bros. game.

But soon after the action came into view, things took a turn for the bizarre.

In its opening moments, Super Mario Land certainly looked like a Super Mario Bros. game, yeah; and it was obvious to me that its rudimentary, basic-looking visuals were meant to evoke memories of Super Mario Bros., after which it this game was clearly styled. But then there was every other aspect of the game--elements that, surprisingly, were working aggressively to create a tone and an atmosphere that were far removed from those that Super Mario Bros.'s visual and musical elements were able to generate. It was as if the designers were trying to take Super Mario Bros. and turn into something that felt oddly contrasting.

You could still squash Goombas (or what looked like Goombas), bounce off of enemies, and go down certain pipes, yeah, but now, for some reason, tossed fireballs would continuously rebound off of surfaces and do so for what seemed like indefinite periods of time, and Koopa Troopers (or, again, what looked like Koopa Troopers) would explode after being stomped! There were Bullet Bills flying through the air, as expected, but now they were instead being fired out from cannons that were emerging from pipes! There were enemies like giant flies and spear-carrying bees--enemy types I just didn't associate with classic-style Super Mario Bros. games. And when I grabbed a Starman, it played not the classic Super Mario Bros. Starman ditty but instead the ... "Can-Can" tune from those Shoprite commercials?!

"This is all just friggin' weird!" I thought.

The more I saw of Super Mario Land, the more clear it became to me that it had absolutely no desire to closely adhere to Super Mario Bros.'s standard conventions. It was eager to develop its own unique personality, I realized, and it was willing to bend as many rules as it had to to meet that goal.

So it just kept continuing to differentiate itself in unusual ways: Its underground bonus areas had bouncy, quirky-sounding music rather than the quiet, mysterious-sounding music you'd expect to hear in a Super Mario Bros.-styled game. The rebounding fireballs were somehow able to collect coins. There were hidden elevator-type platforms, and not beanstalks, that gave you access to high-up places. And, most intriguingly, it had unique bosses! It wasn't Bowser waiting for me at the end of World 1, no, but instead that large sphinx I saw on the game's box cover! And that was really exciting to me for some reason. (Though, it was a thematically similar battle: You could win by taking out the boss with fireballs and then hitting the switch to raise the gate, or by deftly maneuvering your way past the boss and hitting the switch, doing which would bring the battle to a sudden end.)

In fact, there wasn't even the faintest hint of Bowser's presence, and after a while, I became certain that he wasn't even in this game. And that, alone, was quite a big swerve.

At first, its controls seemed to function identically to Super Mario Bros.'s, though my experimenting with them revealed that, no, they really didn't; rather, its basic movement controls were comparably stiff, and Mario's jumps would lose momentum the instant I ceased holding forward on the d-pad. The jumping controls' rigidity rendered the most difficult platforming sequences--mainly any of those that featured moving platforms--so much more tense because of how they required me to tactically halt and then suddenly redirect Mario's jumps. And this was tough for me because Super Mario Bros.'s jumping controls were so ingrained in my mind; I was used to jumps that had sustained momentum and predictable, modulable arcs.

And the game's hit-detection was tough to figure. Sometimes Mario would take damage for what looked like non-contact, and other times he'd pass through enemies and somehow come away unscathed. So when I'd jump toward an oncoming pack of enemies, I was never sure how it would work out for me.

From a mechanical standpoint, Super Mario Land just didn't feel as polished as Super Mario Bros. It was comparatively rough around the edges.

Though, there were areas in which Super Mario Land was actually superior to Super Mario Bros. Its background displays, for example, were so much more appealing. They were similarly minimalistic, yes, but their imagery was more fun to look at and examine; they were populated by all sorts of eye-catching etchings and little depictions like distant mountains, totem poles, bamboo trees, silly hieroglyphics, and other renderings that were so much more interesting than Super Mario Bros.'s comparatively unimaginative clouds, bushes and fences.

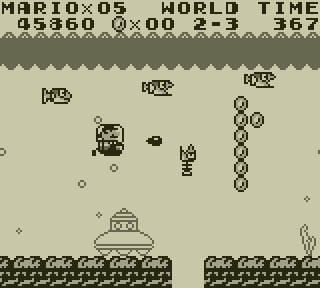

Also, it had more variety to its gameplay. Most notably, it had scrolling-shoot-'em-up-type stages! The final stage of World 2 was one of them. It was an underwater stage but not one of those that required you to carefully swim your way around Cheep-Cheeps and Bloobers, no; rather, it was one in which you piloted a submarine (the one Mario was piloting on the box art!) and blasted things! As you scrolled along, you could shoot all of the aquatic enemies and the floating blocks and do so while freely moving about the screen! "Not even Super Mario Bros. 3 had anything like this!" I thought to myself.

Plus, like I said, Super Mario Land had unique bosses. Whenever you'd make it to the endpoint of a world's final stage, you'd run into one from a group of eclectic boss creatures. And each of the battles was uniquely engaging. Such battles could entail engaging with a stone creature by platforming of the blocks he was throwing at you or using your special craft to target and mow down a mobile seahorse.

And Super Mario Land also had much more in the way of music! Each stage type had its own musical theme. And each of those themes was a delightful little composition that was able to evoke a specific emotion from me. (Though, at the time, I wasn't sure if the composer intended for his or her music to be that deep. I mean, this was a "Game Boy game" after all! Something so bite-sized couldn't have the power to do something as heavy as "evoke emotions," could it?")

But the biggest contrast, still, was how the game felt. Though, I didn't know how to describe that difference; I couldn't identify what, exactly, was making Super Mario Land feel so tonally distant.

"Seriously--what's going on with this game?" I continued to wonder. "Why does it feel so different?"

I decided that the best way to make sense out of all of this was to read the manual. There had to be something in there that explained why this game felt so different, I thought.

Though, in reading the manual, all I discovered was that the game's weirdness had infected that part of the package, too. Reading through it only left me feeling more confused. And I was left with several more questions, like: "What's this 'Sarasaland,' and is it even connected to the Mushroom Kingdom?" "Who the hell is 'Daisy,' and how can she be the 'princess' when Princess Toadstool already holds that title?" "Why do all of the enemies have such odd-sounding names? And why did they change the names of those whose identities have long since been established?" "Why have popular foes like Lakitu, Spiny and Buzzy Beetle been replaced by robots, spiders and dead fish?" "And was this game even made by the same people?"

So I learned nothing. I still had no idea why all of these changes were made, and I was no closer to knowing who or what was actually behind the creation of this game.

Though, don't get the wrong idea, reader: I wasn't mad about any of this, no. To the contrary: I was highly intrigued by Super Mario Land's weirdness; I found it to be very alluring. And I couldn't wait to further immerse myself in the game and spend more time examining its weird elements and drinking them in. And this surprised me because I went in believing that a Game Boy game's content could never be so interesting. Like I said before: In the previous months, I'd dismissed the Game Boy as something "lesser." I kept telling myself that Game Boy games were inherently inferior products.

So I was really surprised that the first Game Boy game I'd ever played was able to evoke such strong emotions.

Super Mario Land was a winner. Indeed it was the star of the show that day, and after I finished my first session with it, I walked away feeling strangely enamored not only with it but also with the platform that gave it life.

The next day, I played Super Mario Land to completion, and I came away from the experience with the same type of contemplative, impassioned feelings that enveloped me after I completed Super Mario Bros. for the first time. I spent the next few hours reflecting on the experience and thinking about its tonal differences--about why I was so fascinated with its weirdness. And I continued to do as much for years in following.

I wasn't bothered by the fact that it was a much shorter game than Super Mario Bros., no (it took me a mere half hour to beat it). I didn't mind that it was very brief when compared to your average console game. I mean, it was a Game Boy game after all! (In many ways, I still perceived portable games to be "lesser.")

I didn't think that its final boss, Tatanga, was quite as memorable a foe as luminaries Bowser and Wart, no, but I could still appreciate that the designers thought to include such an odd character. Because let me tell you: A game this weird demanded the appearance of a cat flying a projectile-firing spaceship. It wouldn't have been Super Mario Land without such a thing.

So in the end, I couldn't have been happier with how my Christmas holiday went.

From that point on, I took my Game Boy and my small collection of games with me everywhere I went. Though, as I quickly learned, there were certain issues that a Game Boy owner had to deal with. First there was the transporting issue: How does one carry around so much hardware at one time and do so neatly? Throwing all of it into a plastic bag just wasn't a good answer; plastic bags tore easily, and when you'd carry them, the items within would shift about and smack into each other and scratch each other up.

Then there was the lighting issue and specifically, "How the hell am I going to play this thing in the car during the nighttime hours?!" How Nintendo overlooked such a thing as backlighting was a total mystery (only to my younger self, of course).

Fortunately, my parents were aware of these issues, and they had the answers. For my 13th birthday, they bought me some Game Boy peripherals: a combo pack that included a magnifier and a light projector; and square, black carrying case that was advertised to hold eight games and a few accessories (by the end, I managed to stuff in about, oh, 23 games plus a link cable).

For much of that early period, though, I didn't need to find space for Super Mario Land because it basically glued to the system's cartridge slot. I played it a bunch.

In the first year or so, Super Mario Land was my go-to road game. Whenever we were on a long trip, whether it was to see friends in Long Island or visit family in New Jersey, I'd always make sure to play it to completion. And anytime our group would travel to Atlantic City, specifically, I'd always make it my mission to beat Super Mario Land before we reached the halfway point--the Exit 100 rest stop, which is where we'd all meet up for lunch. We'd hang out at Kenny Rogers Roasters, the chain that currently dominated New York- and New Jersey-area rest stops.

Those were fun times, I tell you.

The more I played Super Mario Land, the more I appreciated its divergent qualities. The shoot-'em-up stages, though something of a startling deviation, were nicely sewn in and well-executed, I thought; they were a nice break from the standard jump-and-stomp action. I was never a big fan of shooters, no, but I found Mario's brand of flight-based combat to be genuinely fun--easy in difficulty, sure, but nonetheless enjoyable. It was a nice contrast to the bullet-hell-type action that would so frustrate me whenever I'd play arcade shooters (the biggest offenders).

I liked how a stage's upbeat musical accompaniment would suddenly give way to a harrowing boss theme whose alarming tone would serve to greatly increase the intensity-level. Super Mario Bros. certainly didn't have anything like that. No--when Bowser's chamber would come into view, nothing would change; the stage theme proper would simply continue to play, and thus there was no raising-of-the-stakes feel. For that reason, Bowser fights seemed boring in comparison to the ones Super Mario Land offered.

This was just one example of how Super Mario Land's exotic-sounding music helped to separate it from its console cousins and do so in a very significant way.

Then there was World 2's initial stage theme, which I considered to be the game's best piece. I loved this theme because it was wonderfully enchanting and because it had the power to evoke from me strong emotions--conflicting feelings of joyful merriment and wistfulness. And I knew what that meant; I understood what the music was telling me. It was saying, "This is a special time in gaming history and in your life. Please use these moments to fondly reminisce about the old days and enthusiastically wonder about the future."

Whenever I think about Super Mario Land, that World 2 theme is always the first thing that comes to mind. Immediately it starts playing in my head. And when it does, I remember how powerful a piece it is. Never has a tune said so much about the time-period from which it came--about the atmosphere and the spirit of the era.

I say this not to undercut the power of its other musical pieces, no. I adore all of them, too, and do so for similar reasons. I mean, I could never forget the strangely mysterious, chilling Easton Kingdom--the game's recurring cave theme--or the strikingly-enigmatic-though-maddeningly-catchy Chai Kingdom, whose wonderful Asian-sounding strains masterfully define World 4's environments and activities and furthermore encapsulate the entire Super Mario Land experience.

Of course, I can also never forget the game's highly evocative, utterly unforgettable credits theme and what it meant to me. It was a simple-yet-amazingly-stirring tune that was so satisfyingly crowning that it was worth playing through the entirety of Super Mario Land just to hear it.

And after the rocket ship left the screen and the words "The End" flashed, I'd let the credits theme play for an additional ten-plus minutes (or at least until we reached the next toll booth, at which point I'd turn the sound down or switch off the Game Boy because I was afraid that the booth's attendant might see me swaying in rhythm to dinky 8-bit video-game music and think that I was a freak or something), and in that span, I'd lose myself to the music and allow for its equal-parts-inspiring-and-melancholic melody to work its magic and thus provide shape and color to all of the nostalgic images that were currently populating my thoughts.

Really, I wasn't surprised to learn that Super Mario Land and Metroid shared the same composer (Hip Tanaka). It made sense because Metroid, too, was a game whose music could evoke from me contrasting and conflicting emotions and therein inspire me to wonder about the messages it was sending. And, also, it helped to explain why Super Mario Land felt so tonally different. Hip Tanaka was the reason!

I should have known.

Originally I felt as though Nintendo's decision not to fully localize Super Mario Land was peculiar and even a little lazy, but now, after coming to view the game's eagerly disregarding of convention as an important aspect of its personality, I was actually glad that the company didn't fully localize it. The enemies and places retaining their original Japanese names helped to lend the game such a wonderfully "foreign" feel--one that went a long way toward helping it to stand out from the traditional Super Mario games.

So while in reality it actually was Goombas and Koopa Troopers that I was stomping, the simple name discrepancies were enough to make me think that maybe I wasn't--that maybe these enemies were instead members of oddball subspecies or distant cousins of their well-known comrades, and they were the types of characters that could only exist in a weird place like Sarasaland.

And then there were strikingly distinct enemies like the fearsome Pionpi--a relentless zombie-like robed menace that doggedly hopped its way around the Chai Kingdom with its arms extended forward. Stomping it would only temporarily immobilize it--cause it to briefly enter into a compressed state. The only way to truly kill it was to strike it with superballs (a weapon that, naturally, was Super Mario Land's requisite substitute for fireballs). The presence of such enemies helped to further amplify the game's disparate, foreign-feeling vibe.

Super Mario Land's atypical enemies and exotic settings also inspired me to wonder about the world beyond the game--namely about Japan and its cultural obsession with weirdness and about how said obsession was reflected in this game. I'd examine World 3's backgrounds and their curious-looking stone sculptures (originally, because I knew nothing about the world, I called them "George Washington heads," though I later learned that they were instead Moai, which were associated with Easter Island--a place with which Japan, for some reason, is obsessed) and wonder about what it was that inspired the designers to look beyond the traditional and instead populate their game with imagery that was so strange and unusual.

Inspiring wonder seemed to be the designers' goal. That's what I thought when it became clear to me that Super Mario Land, oddly, had an underlying alien theme to it. I'm talking about any of those instances when I'd look to the background and see a hovering UFO with a ladder leading up into it. I could never come up with a solid theory for why those UFOs were there (my most plausible theory was that all of Sarasaland's enemies were actually "alien invaders")! Though, these days, I lean more toward what Jeremy Parish posited--that, actually, the UFOs were what Mario used to travel from world to world (and, again, Mario piloting UFOs would be just the type of randomly weird thing that Super Mario Land would do).

We'll probably never know for sure. And, really, I hope that we never do. It's more fun to wonder, I say.

For about a half decade in following, I continued to derive a consistent level of enjoyment from Super Mario Land. In the first few years, the enjoyment came via all of the time I spent joyfully playing it during our many long drives, and later on, it came from my playing it on the Super Game Boy, which appealed to me because it allowed for me to play beloved Game Boy games like Super Mario Land on my TV. And truthfully, I never wanted to move on from it. I had to do so because my SNES went directly into the closet once the N64 took over my life, and my Game Boy died because I stupidly left the batteries in for too long; they corroded and thus destroyed the battery terminal.

So, I'm sad to say, I was cut off from Super Mario Land for multiple years. I didn't get the chance to play it again until the year 2000--until the dawn of emulation. I was happy to have access to it, yeah, but I couldn't deny that playing it on an emulator just wasn't the same. Something important was missing: the gaming-in-the-palm-of-your-hands part of the experience. And since I'd recently become highly partial to portable devices, I found myself yearning to recapture a Super Mario Land experience that was as close to the original as possible.

Thankfully I got my wish: On June 6th, 2011, Nintendo introduced the 3DS Virtual Console, and one of the first titles available was Super Mario Land! I purchased it right away (even though I had an aversion to buying games I already owned--even if my copies were broken--because doing so made me feel like a sap). I was aware of its "flaws" (it had stiff controls and indecipherable hitboxes, and it was really short in length), yeah, but, really, I never gave any serious thought to such things. I liked it for what it was, and I was happy to be reunited with it. And that evening, I had a lovely time running, jumping and stomping my way through Super Mario Land and revisiting the strange and unusual Sarasaland, to which I hadn't been in ten long years.

And in that half hour or so, Super Mario Land worked its magic on me. It transported me back in time and in doing so reminded me of the days when there were few things more important to me than playing video games and thinking about their wonderfully weird worlds. And of course, the trip was helped along by World 2's emotionally rich theme music, which, in those moments, had never been more powerful.

I'm happy that I got one other opportunity: My having access to a portable version of Super Mario Land allowed for me to replicate my old routine. During the summer of 2012, I took my 3DS with me when I drove upstate to visit my father. And in the interest of creating an ideal Game Boy experience, I made sure to give Super Mario Land a play during sundown and specifically in the dining area of my father's huge backyard, which is surrounded by woodland and also the soft, soothing sounds of nature. And I tell you: Playing Super Mario Land somewhere other than home--in a place separated from it by hundreds of miles of road--felt oh-so-right, and I hope that I get the chance to do it again sometime in the future.

When I first played Super Mario Land back in 1990, I thought of it as just a "Nintendo property" because I was under the assumption that every game released by the company was produced by one monolithic group (a group whose members had funny names like "Miyahon" and "Ten Ten"). I didn't know that Nintendo had separate development groups or that some fellow named "Yokoi" was doing his own thing and trying to connect with players in a very different, very profound way. All I knew was that Super Mario Land looked like other Super Mario games, yes, but somehow felt worlds apart.

I got that sense because Gunpei Yokoi, creator of the Game Boy, and his band of outlaws accomplished something for which they had a knack: deviating from the norm and creating amazingly unique worlds whose unconventional, thought-provoking themes inspired players to wonder. And because their group, R&D1, did this so successfully, we came to form long-lasting emotional connections with its games.

And those connections, I'm sure, will live on forevermore.

No comments:

Post a Comment