How "anything" became the only thing that could alter the course of history.

It all goes back to my painful experiences with the original Castlevania.

No matter how many attempts I made, I just couldn't do it. I couldn't beat the game's fourth stage. Its bosses, Frankenstein and Igor, seemed to be unbeatable. And all I could do was become increasingly dispirited.

I'd played through and beaten punishing action games in the past, sure, but none of them prepared me for this type of challenge. Most of them were comprised largely of obstacle- and puzzle-based challenges, and the closest thing they had to an end-boss was Bruce Lee's "devil"--a completely immobile projectile-spitting demon that you could beat simply by sprinting forward. So at this point in my life, I was new to the idea of "super-tough end-stage" bosses.

I wasn't pissed because of the number of thrashings I'd taken, no, but because of the way in which each battle was playing out. It was the same thing over and over again: I'd somehow get Frankenstein and Igor down to one remaining health unit, and then, out of nowhere, I'd be conveniently struck and killed by a fireball whose trajectory seemed to be determined more by CPU clairvoyance than by actual calculation. "Now how the hell did the game know that I'd be in that spot at that moment?!" I'd shout in exasperation.

Those types of deaths were soul-crushing.

I'd never felt that way before. I'd felt discouraged, sure. I'd felt frustrated by games whose challenges were extremely demanding. But I'd never been beaten down like this. I'd never been repeatedly denied victory, in the most painful fashion, by bosses whose movements and attacks were so random that I couldn't possibly read them or react to them in time.

That Frankenstein and Igor battle soured me on the entire game, and as I was in the process of angrily switching off my NES and yanking out the cartridge, the only thing I could think was "I never want to see Castlevania again!"

It was a heartbreaking way for my Castlevania experience to end. And I say that because I was in love with the game's subject-matter and setting and thus desired to experience it in full, but I couldn't do so because one of its elements was making it feel impenetrable. Instead, I was content to completely abandon it.

That awful experience colored my judgment to such a great degree that I wouldn't even let myself entertain the notion of purchasing Castlevania II: Simon's Quest even though my first impression of it was very positive--even though I was fascinated with its divergent qualities and enamored with its visuals and setting.

No sir--I was done with the Castlevania series, and there wasn't anything out there that was going to change my mind!

But then something unexpected happened--something that altered the course of my gaming history and did so in the most profound way.

It's a story I've recounted a few times before: It was the winter of 1990 and a time when I was out of options. I'd played all of my favorite games to death, and I couldn't find anything else to play because I had no interest in any of the other games that were currently on the market or any of the games that were listed in Nintendo Power's upcoming-releases ("Pak Watch") section. I was desperate for something new, but I just couldn't settle on anything. I wasn't sure what I wanted.

That's when the gears went into motion.

So one day, my brother, James, and his friends decided to head on over to one of the local electronics stores and buy themselves some games (James was no doubt planning to empty out a few bargain bins and scoop up a whole bunch of NES games he'd never actually play). Before leaving, James came upstairs, walked on over to the den, and asked me, "Are there any games you want me to pick up for you while I'm at the store?" Having nothing in mind but still desperate for a new game, I decided to leave it to chance; I handed him the $40 and told him to "just get anything," trusting his judgement in light of the numerous previous instances in which he had acquainted me with the kinds of games I would ordinarily ignore or overlook and therein helped me discover those that would go on to become some of my favorites.

I don't know whether to call it a random act of fate or divine intervention by the gaming gods, but something steered James toward Castlevania III: Dracula's Curse. And that's the game he decided to buy. It was a recent release, so he (or one of his friends) assumed that (a) I hadn't heard of it and (b) I'd have a natural interest in it because it was a "new game" (because, of course, "new game" was synonymous with "good game").

Though, I had, in fact, heard about it (in the previous months, I'd seen Castlevania III: Dracula's Curse advertisements prominently displayed in just about every store I went to), and, no, I didn't have any interest in it. That's why I was annoyed when James came into my den and presented it to me. "Why would I want to play a sequel to a game that just plain abused me?" I thought to myself when I saw its box.

I wasn't going to return Dracula's Curse, no, but I also had no intention of giving it any serious attention. I was only going to sample it and do so because I was obligated to--because I'd spent real money on it, and because I owed to my brother, who was nice enough to include me in his latest game-hunting effort, to at least spend a half an hour or so with it.

So I went up to my room and dispassionately inserted Dracula's Curse into my NES. I had no idea what was awaiting me, but I was prepared for the worst.

That's probably why I was so caught off guard by the game's intro, which was surprisingly interesting. It was presented in such an innovative way: Its imagery and text were displayed on the individual cells of what appeared to be an "antique" film reel! This, I felt, was a very appropriate presentation for a game (and a series) whose story was set in a much-earlier age.

Also, I was struck by the intro's accompanying musical theme--a profoundly melancholic tune that added so much gravity and weight to the story that was being communicated; this tune and the darkly shaded imagery combined to create an atmosphere that was remarkably grim- and somber-feeling, which was a striking tonal change from Castlevania, whose story, contrastingly, had a non-serious-monster-movie vibe to it.

The intro told me that Dracula's forces had ravaged most of Europe, as they were apt to do, and that the previously banished Trevor Belmont was called upon to counter the threat. And I was surprised by this backstory because it was so dark and bleak in nature. I just didn't think that the Castlevania series took its subject-matter that seriously. I thought it was all about goofy-fun monster-hunts.

From what this intro was telling me, though, Castlevania's world had way more depth and complexity to it than I imagined.

I took all of this as a sign that Dracula's Curse was something different--something wonderfully divergent. "Maybe I made a mistake in overlooking this game," I thought.

And what I saw in the first few seconds was very encouraging: The praying Trevor, in reaction to a powerful lightning strike, stood up, turned toward the camera, majestically flipped his cape over his shoulder, and then struck a pose that said, "This is going to be epic!"

Though, as soon as I took control of the action, I became aware of a very disappointing fact: Dracula's Curse looked and played exactly like Castlevania (which I would have known had I taken even as much as a glance at Nintendo Power previews)! It had the same presentation, the same controls, the same gameplay formula, and, apparently, the same weapons and items. And Trevor was simply Simon Belmont with long hair and a headband; he sported the exact same color-scheme, and his movements and animations were identical to Simon's!

Dracula's Curse, it appeared, was one big copy-paste job! Upon realizing this, all I could do was groan.

All of this felt so cheap to me because Super Mario Bros. 3 had just demonstrated how you could return to your roots and do so while dramatically changing things up. Dracula's Curse's creators apparently missed that lesson and instead settled for replicating the original work down to the last pixel. The Mega Man series' developers also recycled hero sprites and animations, sure, but they at least had an excuse for doing so: The hero was the exact same guy! Trevor, though, was not Simon Belmont and shouldn't have looked like him.

"What gives?" I silently questioned.

Looking for answers, I turned to the game's manual. And as I skimmed through it, I learned that, indeed, Dracula's Curse was mechanically identical to Castlevania, and it contained all of the same weapons and items. There were also some mentions of "alternate routes" and "ally helpers," but I gave no attention to such things; I wasn't that invested in the game. All I wanted to do was confirm whether or not Dracula's Curse was a total retread of Castlevania. And it was looking as though it was.

Though, as I continued playing into the first stage, I started to notice that there were some significant differences. The most obvious was the tonal difference. Much like the intro, the stage's music and visuals were darker and bleaker in character; they painted a picture of a depressive, dilapidated world that was running short on hope.

The game's imagery had a lot to say: The nearest background plane was populated with wrecked buildings and ruins that were slowly being enveloped by the vegetation that would soon become their only exterior; and the distant plane was dominated by the silhouettes of decayed arches, pillars and bridges. I couldn't help but gaze at this imagery and think about the messages it was sending.

The stage's musical theme, too, was doing some heavy lifting. It was a strikingly haunting tune whose combination of mesmerizingly complex, intertwined note strings and a powerfully moody-sounding bassline provided the game's world some very real emotional depth. Its was an evocative symphony that gave me valuable insight into the nature of said world.

I couldn't deny that Dracula's Curse looked and sounded amazing. And that was based on what I'd seen and heard in just its very first segment (I hadn't even passed through the first door)!

In the segments beyond, the visual feast continued. First I climbed my way up a church whose walls were adorned with stained-glass windows that were so detailed that you could identify each of the angelic figures that appeared in their separate frames. Then I traversed the town limits, which gave view to a residential area (or what was left of it) and all of its ravaged abandoned homes, whose depressively brown-hued exterior walls spoke of the method of destruction. And, finally, I passed through a dreary, neglected graveyard whose dilapidated structures and horribly decayed zombie inhabitants served as the perfect symbol of the fate that had befallen the land.

Oh, and the graveyard's background was populated by an awesomely menacing, darkly shaded mountainscape (my favorite!), the inclusion of which immediately made Dracula's Curse worthy of my stamp of approval!

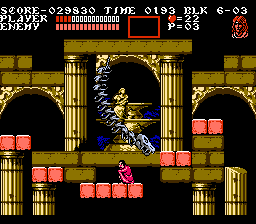

This visually and aurally impressive opening stage culminated in a nicely scripted boss battle against the Skull Knight. It wasn't a particularly difficult boss battle, no, but the design of it--the depth of its structuring--told me a lot about the craftsmanship that went into the making of Dracula's Curse. There was a lot to it: In the lead-in to the battle, the Skull Knight suddenly formed from what looked like a lifeless heap of bones. After it finished constructing itself, it proceeded to chase me about the battlefield and do with a surprising amount of mobility. Throughout the battle, it reflexively blocked my whip-strikes with its shield. And when its health was fully depleted, it died spectacularly; it screamed in agony before being engulfed by flames!

The NES wasn't known to have strong voice-sample output (NES games' voice samples were usually some combination of scratchy, compressed and garbled), but somehow Dracula's Curse's creators managed to program in highly audible, convincing-sounding death throes! "These cats really went the extra mile!" I thought to myself.

My sense, now, was that Dracula's Curse was clearly a next-level game. It was pulling off technical feats that seemed to be far beyond what the NES' hardware was actually capable of producing! I mean, this was the same console that was previously incapable of fully reproducing a simple game like arcade Donkey Kong (because of storage and memory limitations, an entire stage had to be cut). But now, suddenly, it could produce high-end-looking games that could convincingly pass as next-generation-console launch title?! "Konami's developers have to be wizards!" I thought. (I was of course oblivious to the existence of expansion chips.)

I was astonished by Dracula's Curse's visual quality. It was one of the best-looking video games I'd ever seen. Certainly it was a big step up from Castlevania, whose background visuals were nicely rendered, sure, but they were often utilitarian and sometimes sloppy- and incoherent-looking. Dracula's Curse's visuals, in comparison, were consistently distinct-looking and in every instance cleanly rendered, richly detailed, and easily identifiable. They were in their own league.

On the whole, though, I remained skeptical of Dracula's Curse. What I'd seen to that point was assuring, yes, but still I had a major concern. Mainly, I was worried about the opening stage's length and content and what both of them portended; I took it as an ominous sign that the stage was entirely too long and that Medusa heads, hunchbacks and bone pillars were showing up so early on in the game. Their mere presence suggested that Dracula's Curse's difficulty would be high from the start. "If Castlevania's most-troublesome enemies are showing up this early in the game," I wondered, "then what type of new, even-more-nightmarishly-awful creatures could be waiting for me in the later stages?"

All I could think was "How much worse can this get?" and "How soon am I going to run into this game's 'Frankenstein and Igor'--the impenetrable wall on which I'll only be able to beat my head?"

Still, I couldn't deny that I was very intrigued by what Dracula's Curse had shown me. I wasn't sure that I possessed the skill necessary to play through and beat it, no, but I saw no reason to let that feeling stop me from exploring it further.

So I played on. And after I completed the first stage, I was given a choice between two separate paths: One led to a clock tower, and the other led to a woodsy area. I recalled that the manual mentioned something about this; it spoke of "alternate routes" and having to make choices. At the time, I didn't give much thought to the concept. "It probably doesn't add much to the game," I figured. But now, when I was seeing it in practice, I was genuinely interested in finding out how it worked.

Though, again, I was concerned about one of the options and what it portended. "A clock tower this early, though?" I questioned in a nervous way. "Wasn't the clock tower Castlevania's toughest stage?!"

I decided to go there anyway--mostly to see if my fears were founded.

And once again, what I was seeing and hearing made me temporarily forget my fear. Immediately I was captured by its enchanting, evocative musical theme; it was a stirring-yet-sobering piece that inspired me to think about the game's world and wonder about how it fell into such a despaired state. I was hypnotized, also, by the clock tower's imagery and especially by the amount of activity that was occurring. Its backgrounds were filled with animation; everywhere I looked, I could see (a) gears and cogs of all shapes and sizes spinning dutifully and (b) series of chain-linked pulleys orchestrating wonderful symphonies of movement.

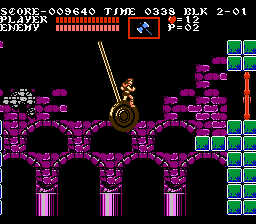

This was a far cry from what I saw in Castlevania's clock tower, which in comparison was disappointingly static and lifeless; its gears were motionless, and those placed on the sprite layer were nothing more than simple platforms. Dracula's Curse's gears, though, were incredibly lively and highly functional. I was able to walk and traverse upon large turning gears, of both the vertically-positioned and flat-laying varieties, and ride along their surfaces; and I was also able to hop onto and ride giant swinging pendulums whose animations impressed me so much that all I could do was observe them and wonder, "How in the world did the designers do that?"

I only had one issue with the stage: I wasn't happy about the fact that it was swarming with Medusa heads, which were serving to make the nerve-wracking platforming challenges more harrowing than they needed to be. The upside, though, was that my constant interactions with them were helping me to become more adept at reading their movements and responding to them. (The training that took place here would prove to be a monumentally important aspect of my Castlevania history.)

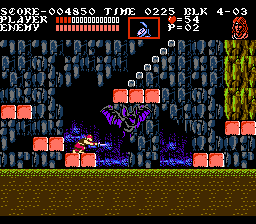

My long climb up the brilliantly designed clock tower culminated with a battle against the wall- and ceiling-crawling Nasty Grant (who I initially thought was a "giant hunchback"). And when I defeated him, I was introduced to the game's "ally" system: Grant, after transforming into a human (who I also thought strongly resembled the series' hunchback enemy), requested that I allow him to join me in my mission! I accepted his offer, of course, and eagerly prepared to move on to the next stage.

And that stage was ... the clock tower?! Again?!

Evidently, yes. It appeared that I now had to descend down the same tower I just climbed and re-traverse all of the same rooms--only now in reverse! "That's wild!" I thought to myself, having never seen anything like this in a game. Traveling back to a starting point in a stage-based action game was so unorthodox yet so cool. I was fascinated by the idea.

Along the way, I made sure to test out Grant's abilities. I couldn't keep him active the entire time because he was just too physically weak and took too much damage, but in the periods when I was using him, I had great fun experimenting with his unique wall- and ceiling-crawling abilities (not so much, though, in the moments when I plunged to my death because of unfortunate corner-crossing control hiccups). I couldn't help but marvel at these abilities; they were so amazingly inventive and so "advanced"-feeling; they did so much to reinforce the notion that Dracula's Curse was a "next-level game." And the best part was that I could use them to climb over walls and create my own shortcuts! Also, because I was now descending, I could heedlessly drop down vertical passages and thus skip over large stretches of the stage!

Talk about fun!

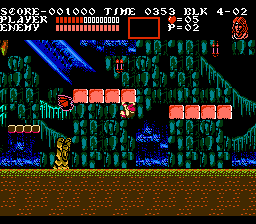

And the stage's background imagery was super-detailed, especially in the opening segment, which displayed two layers of impressively rendered, strikingly-well-shaded trees and between-spaces that were rife with creepily twisting foliage and other intriguingly designed objects that did well to create visual depth and evoke feelings of wonder.

I was enchanted by the forest's background visuals. I focused on them the entire time I was there.

The stage's middle portion featured another one of the designers' awe-inspiring visual effects: a fog that was formed from multiple layers worth of scrolling objects. The fog covered the background and foreground layers, and so it was able to exert its spooky influence everywhere. It worked to partially obscure the action that was occurring on the sprite layer as well as the lightning bolts that were intermittently ripping across the sky. I was amazed that the NES could pull off such an effect.

Strangely, though, there was no boss waiting for me at the stage's endpoint (back then, this was unheard of). Rather, there was only a door. When I passed through it, I was immediately taken back to the map screen and asked to select between two paths: a high road and a low road. I decided to take the high road because its luminous statues were more welcoming-looking than the lower road's dreary-looking marsh.

What struck me as odd was that the high road appeared to be not a new stage but instead an extension of the forest stage; it contained the same type of woodsy environments, and it recycled the fog effect (which was used here, I think, to represent a flowing river). I didn't know what that meant. "Is this a new stage or not?" I wondered. (And I'd continue to wonder about it for decades. For whatever reason, I just wasn't able to fully grasp how certain elements of Dracula's Curse's alternate-routes system worked.)

I was quite surprised by what happened after I defeated the stage's boss--the hammer-wielding Cyclops: One of the statues in the background suddenly sprang to life and revealed itself to be human; he was a man (I thought) named "Sypha," and he requested that I allow him to join me in my mission. I was surprised by this because I assumed, after what happened with Grant, that only bosses would become allies. So I saw this as a complete curveball.

I agreed to accept "his" help, and I thought to myself, "Oh cool--now I have two uniquely performing allies at my side!" Unfortunately, though, the game had other ideas: The moment Sypha joined the party, Grant left it. It turned out that you could only have one ally at a time. I was disappointed by this because I was hoping to abuse Grant's climbing ability!

At the start, I wasn't especially happy with my choice because Sypha was just as physically weak as Grant and had none of his agility. He seemed like a huge downgrade. Though, I was soon given reason to believe that it was in fact in my best interest to have him at my side. The magically gifted Sypha, I learned, was actually a beast. I became aware of such in the Haunted Ship of Fool's opening area, after I obtained a fire spell; I watched on as the spell's fiery blast absolutely tore through the irritating Dhurons and all other undead scourges. The spell was a killer weapon; it had great range and was more powerful than even Trevor's fully powered whip.

And in that moment, I thought to myself, "This ally system is brilliant!" Every helper, it seemed, could contribute something unique and wonderful. And now I couldn't wait to find out what the next ally character would bring to the table! I was hoping that there were more than three of them--that the manual, for the sake of surprise, was refraining from mentioning additional allies.

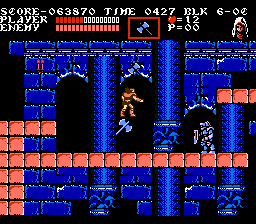

It was hard not to notice, though, that Dracula's Curse's difficulty was quickly ramping up. The minor enemies were becoming craftier (and more apt to knock me into death pits), mid-bosses were being thrown into the mix, and the game was now introducing platforming challenges that required me to jump up to blocks that were placed three tiles over and one tile higher than the ones on which I was currently standing. So basically I now needed to execute pixel-perfect jumps--something I was never great at.

In my earliest sessions with Dracula's Curse, I had a strong tendency to come up short on such jumps. I'd usually psyche myself out and either jump too late or just walk into the pit. It was a mental hurdle that I wasn't quick to overcome. Ordinarily these issues would have turned me off to a Castlevania-titled game, but here, on this day, they didn't. Dracula's Curse was introducing the types of challenges I feared, yeah, but still I wasn't deterred. I felt capable because I had Sypha and her deadly spells at my command.

Without realizing it, I'd become deeply engrossed in Dracula's Curse. Its gorgeous visuals, incredibly evocative music, cool graphical effects, and amazingly wondrous atmosphere had immersed me in ways that few others could. I was enamored with the game's stage environments and all of the imagery that helped to define them. I couldn't stop thinking about the clock-tower gears that spun ceaselessly and did so for a not-clearly-defined-and-thus-mysterious purpose (seriously--why do video-game clock towers always have 1,000-plus gears that seem to do nothing?); the darkened evergreens that spoke of the forest's size, scope and influence and helped it to generate its rich atmosphere; and the lightning bolts whose ferocity made it seem as though the world, itself, was a hostile force.

I was impressed by everything that Dracula's Curse was showing me. It was clearly a top-level video game. And by the time this first session came to a close, I'd made up my mind: I was going to continue playing Dracula's Curse.

And in the following days, I played through and completed Castlevania III: Dracula's Curse. It was a mighty struggle. It took me several hours and a great many attempts to successfully clear the game's most difficult segments and stages. I was almost broken by those like the towers' bone-dragon-infested vertical rooms and Castlevania's painfully long penultimate stage, which was comprised of a combination of every one of the game's most insidious action sequences and platforming challenges; and, to make it worse, it was home to the ultra-tough Doppelganger boss, which would beat me down every time.

I was so incapable of dealing with Doppelganger that I had to resort to using a cheap tactic that I read about in Nintendo Power: The Doppelganger was vulnerable whenever it was morphing, so you could easily take it down by continuously switching between allies and sneaking in hits while it was still stuck in its transition phase.

But the point was that I beat Dracula's Curse and overcame its challenge. I was driven to do so because the game was just too good. It was the product of pure ambition, and for that reason, I felt that as though I'd be robbing myself of a monumental gaming experience if I didn't see it through to the end. And that's what I would have done had I given up when things got tough. I would have sadly abandoned one of the best video games ever made.

I loved Dracula's Curse so much that I returned to it many times in the following weeks and months. Though, in that early period, I wasn't very adventurous. I tended to gravitate toward the easiest route--the one that took me through the Haunted Ship of Fools and subsequently placed me on the shortest, most linear path the castle. I'd always make sure to visit the clock tower and pick up Grant (mostly because I loved the clock tower stage), yeah, but then I'm promptly dump him for Sypha (who, it turned out, was a woman!), who was more valuable to me because of how she could destroy bosses.

My original thinking was that I didn't need to explore any of the alternate routes because the one I was taking was already offering me a satisfying amount of gaming content (and, to be honest, I was a bit intimidated by the alternate routes because of what I'd read about them in Nintendo Power; apparently they contained most of the game's most-challenging stages). Though, because I was really interested in finding out who Alucard was and how he performed, I decided that it was actually in my best interest to take the lower route and find out what it held.

It was just unfortunate that Alucard wasn't as amazing as Nintendo Power made him out to be. His fireball attack, even when it was it fully powered and thus three-directional, was pathetically weak, and, in most instances, it couldn't even one-hit a basic skeleton; and it was completely useless against bosses. It was cool that he could transform into a bat and fly over obstacles (trouble spots like the cavern sections that were crowded with those headache-inducing mummy men) and help me to access shortcuts, sure, but this ability didn't compensate for his offensive futility; it wasn't going to help me take down tough bosses.

Grant wasn't exactly an offensive powerhouse, no, but he could at least wield sub-weapons. Alucard, sadly, could only use the stopwatch!

All I could do was wonder, "How can this guy possibly help me beat Dracula?"

Still, it was worth taking the lower route because its stages contained more in the way of wondrous environments, wonderfully haunting music, and impressive sequences.

One of the most memorable stages was the sunken city. It was annoyingly lengthy and frustratingly difficult (mostly because it was infested with skeledragons), yes, but what occurred in its second half was super-impressive: While fleeing the scene, the Bone Dragon King boss crashed through a dam and thus caused massive flooding. So now I was required to chase down the Bone Dragon King and do so while outracing the rising water! And when I reached the stage's end, I had to finish him off while trying not to drown! It was an exciting sequence, I thought, and I continued to feel that way even during my 40th attempt to clear it.

Though, conversely, I absolutely hated the mountain-range stage--particularly its second half, whose opening platforming segment could only be described as the most painfully tedious game of Tetris you could ever play. Seriously--all you did was jump back and forth for several minutes and wait for blocks to fall into place. The block-pattern was predictable enough (at least until you reached the segment's top portion, at which point the pattern would inexplicably change), but still I kept finding new and inventive ways to jump into blocks and thus get knocked into pits (this was happening because I was simply too impatient).

This is where Alucard actually proved to be valuable. Eventually I realized that I could use his bat ability to simply fly up and around this entire mess! The only problem was that I could only employ this tactic if I reached this segment with a lot of hearts in the tank and an adequate amount of health (I tended to crash into blocks while flying upward). If I had 5 hearts or less, though, this was a non-option, and I'd have no choice but to patiently wait for the blocks to pile up. And few things in gaming were as boring as that.

And that wasn't even the worst of it. What followed was a series of excessively long, brutally difficult action segments that culminated in a fight against a trio of bosses: a the Mummies, the Cyclops and the Leviathan (which, I thought, bore an uncanny resemblance to Castlevania Dracula's second form). It was a complete marathon, and I'd be lucky if I had more than four bars of health when I reached the bosses.

My desperate desire to avoid traversing these segments was a big reason why I favored the upper route. And if the trade-off was that I wouldn't be seeing Alucard very often, then oh well.

Though, still, I had a strong appreciation for everything that bottom route contained; I saw it as pure gravy--a wonderfully enriching topping added to already-deeply-satisfying dish. I was already a huge fan of Dracula's Curse, yeah, but now, after experiencing even more of its amazing content and loving the majority of it, I couldn't think of it as anything less than an all-time-favorite.

So yeah--I simply loved Dracula's Curse. I loved observing its world, listening to its sounds, engaging with its enemies and environments, and exploring all of its wondrous spaces. There was no other game like it. No other game allowed me to climb up and then descend down a massive clock tower, balance my way across series of unsteady masts, hop onto and off of large spinning gears and giant swinging pendulums, solidly freeze a stream of water and all of its inhabitants and then walk upon and platform off of them, race through vertically scrolling rooms, chase after a bone dragon while racing against rising water, and travel multiple routes.

For those and plenty of other reasons, it was one of the best video games ever made.

Most importantly, Dracula's Curse got me back into the Castlevania series. Now that I was confident in my ability to beat exceptionally difficult games, I felt the desire to return to the original Castlevania (a game that my friends and I considered to be "impossible") and make the effort to finally take down Frankenstein and Igor--the dastardly duo that had so tormented me--and overcome all of the challenges that lied ahead.

And it worked out. My improved skills (and some heavy holy water abuse) helped me to beat Castlevania. And subsequently, it, too, became one of my all-time-favorite games. I came to have a strong appreciation for everything it did. And it was all thanks to Dracula's Curse and what it had taught me.

In the following years and decades, I returned to Dracula's Curse on a constant basis, and each time I played it, I made sure to derive maximum enjoyment from the experience. I made sure to drink in the game's every wondrous visual, its every amazingly evocative tune, and its entrancingly dark, emotionally saturated atmosphere. And I made sure to have a great time with a game that I considered to be a masterpiece--one that was able to defy its host platform's limitations and prove itself to be transcendent.

Dracula's Curse did for the Castlevania series what Super Mario Bros. 3 did for its respective series: It took it to the next level. It helped to establish it as a top-tier video-game series. And its success opened the door for more of greatest games we'd ever play. That's why I'm so thankful for it.

And as I grew up and became a more-skilled player, I came to value Dracula's Curse's (and the entire Castlevania series') brand of challenge. My desire to be challenged by it was what fueled a countless number of revisits. I wanted to be great at Dracula's Curse. I wanted to master it. And in time, I did. I became capable of completing it without suffering a single death (no matter which route I took), the thought of which would have sounded implausible six months earlier.

That was the power of Dracula's Curse.

Not much has changed since then. I still return to Dracula's Curse on a regular basis, and each time I do, I make the same effort to derive maximum enjoyment from it. I do this because it's a special game, and that's how it deserves to be treated. Dracula's Curse means the world to me.

In recent months, I've been spending a lot of time with the Japanese version of Dracula's Curse (Akumajou Densetsu), which, you might know, has some major differences. For one, its music is enhanced by Konami's specially created VRC6 expansion chip, which allows Famicom games to use three additional sound channels; and consequently, it has superior instrumentation and thus more emotional depth to it. Does it blow away the NES version's music, like some would have you believe? Not really. But it's still remarkably-well-composed music. So it's definitely worth your time to head over to Youtube (or my site) and listen to it.

Also, ally Grant wields throwing-daggers rather than a short, weak combat knife. Hunchbacks are replaced by gremlins (which I was shocked to learn debuted here and not in Super Castlevania IV). Some enemy sprites, like the mad frog's and the mummy man's, differ (the North American versions of these characters were made to look meaner because, apparently, Japanese companies thought that Westerners were obsessed with edginess and wouldn't buy games unless they contained characters who wore scowls on their faces). And there are a great many design and mechanical differences (they're too myriad to list here; you can read about them on my site).

I tell you: Akumajou Densetsu's is an absolute treasure trove of strange and interesting differences. I learn about a new one each time I play it.

Honestly, I could spend five more hours and use up 10,000 more words telling you about the many ways in which Dracula's Curse positively impacted my life, but out of respect for your time, I'll refrain from doing so.

Instead, I'll keep it simple and say that Dracula's Curse has three important distinctions: (1) It helped me to see the original Castlevania in a new light and come to cherish it. (2) It was instrumental in elevating the Castlevania series to the very top of my gaming pantheon and earning it a place alongside the stellar Mega Man, Metroid and Super Mario Bros. series. And (3) it influenced the course of my life. Without it, I wouldn't be where I am today, and I wouldn't have met so many amazing people. My life would be emptier.

And, really, that tells you everything you need to know about Castlevania III: Dracula's Curse.

No comments:

Post a Comment