How the jungle's population of bats and birds destroyed my will to continue.

Growing up, my perception of the different gaming platforms--consoles, arcades and home computers--was that they were wholly disparate entities that existed within completely separate universes. Each platform's system of laws was so incredibly unique that to switch from one platform to another was to essentially cross over to another dimension.

And because each platform was so different, any game or game series that was made specifically for it essentially belonged to it. Such a game or game series could never be faithfully ported to another platform because all of its values were intrinsic to the platform that birthed it.

That's how I viewed the medium.

And that's why I was so shocked when while browsing through my brother's Commodore 64 disk case, I came across a game called Pitfall II: Lost Caverns (which, like so many other games, simply appeared in there one day without explanation).

"What?!" I thought to myself as I stared at the game's label while in a state of disbelief. "They made a sequel to an Atari 2600 game and put it on the Commodore 64!? When the hell did this happen?!"

(I couldn't have known the answer to that second question because back then, in 1985, there were only a few video-game-focused magazines, and none of them covered computer games. Also, I wasn't the type of person who would actively seek out such information or even know where to look for it.)

"That can't happen!" I thought to myself. "You can't make a sequel to an iconic console game and put it on a computer! Consoles and computers are completely different things!"

Putting the sequel to an Atari 2600 game on the Commodore 64 had to be a violation of some type of natural law, I thought.

In truth, though, I wasn't upset by this development, no. Rather, I was greatly fascinated by it. I was fascinated by the idea of a game series jumping from one platform type to another (making a "radical defection," as I called it). And I was eager to find out what a computer-focused Pitfall game looked like and how it played.

So I promptly loaded it up.

What immediately worked to shape my opinion of Pitfall II was its contrastingly somber-feeling vibe, which was being strongly communicated to me by everything I was seeing and hearing in just the opening moments. "There's something darker and more serious about this one," I thought to myself as I examined the starting screen's visuals and listened to the game's main theme.

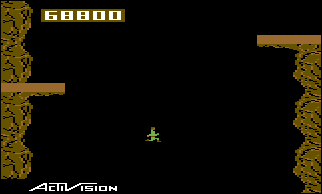

On the surface level, Pitfall II was very similar to its predecessor. Its traversable environments were formed from the same narrow orange-brown surfaces, the same rectangular gaps, and the same spaced-pegs ladders. Its backgrounds were comprised of assemblages of spaced-out trees. And it starred the same green-clad ostrich-necked hero ("Pitfall Harry," as I now knew him) who of course animated the same exact way. Though, for one very specific reason, I wasn't yet prepared to call Pitfall II a retread: Its curiously enchanting tonal differences were telling a very unique story, and therein they were conveying to me that Pitfall II was actually something more--something entirely new.

And because I was so entranced by the game's strong sense of atmosphere and so fascinated by the nature of its existence, I was convinced that I needed to further inspect it and that my doing so would lead me on a journey through a strange and unusual world whose size, scope and depth of emotional conveyance were far beyond anything that any other game had ever displayed!

Going in, I assumed that Pitfall II's action would occur in silence because, well, that's how it was in the original. "Pitfall is all about that silent ambiance," I thought. That's why I was so surprised when music kicked in the moment I pressed the F1 key to start the adventure. The immediate introduction of sound was such a startling difference.

By that point in my life, I'd been around the Commodore 64 for a couple of years, and I'd been trained to expect that my C64 games would emit a certain type of sound. I expected that each newly discovered C64 game would produce music that was synthesized-sounding and thus highly energetic. But that's not what Pitfall II's main theme gave me, no. It was neither of those things. Rather, it was strikingly divergent. Its instrumentation was atypically acoustical-sounding, and its melody was softer and more subdued in tone. And consequently, it had a curiously unique power: It was able to evoke feelings of wistfulness and longing. Though, I couldn't say what, exactly, it was making me long for; all I knew was that it was controlling how I thought and keeping me in a reflective state.

The way I perceived it, Pitfall II's was an "adventurous-sounding" musical theme and the type whose purpose was to define both the mission's nature and the world through which I was traversing. It was there to set the mood, guide my emotions, and tell me how I should feel about the game's environments and the creatures that inhabited them. ("These frogs and birds aren't really enemies, no," the music's mellow vibe told me. "They're just simple animals behaving in an instinctually carefree way.")

Pitfall II's music (much like the future Metroid's) had the power to shape how I thought about the game's every aspect. It was always able to utterly engross me and inspire me think deeply about the state of whichever environment I was currently exploring.

And the game's visuals, I came to realize after subsequently returning to the original Pitfall, were actually pretty impressive; they were more of an upgrade than I originally thought (my mental images of Pitfall were mostly shaped by my imagination, so I forgot how simple and flat they were in reality). Pitfall Harry's running animation had the benefit of more frames. Platforms had rocky, craggy undersides. Convincingly drawn cavern walls replaced primitively rendered brick walls. And the trees that populated its background were so much more detailed; they now had curved and contorted trunks and lushly colored, highly detailed crowns.

I loved the trees, in particular, because of how they were designed and how they contrasted against the pitch-black back layer. The visual of twisted trees working to conceal the darkened background served to create such a rich air of wonder and mystery. Whenever I'd play Pitfall II, I'd stop and gaze at its backgrounds and think, "What's going on behind those trees? What are they hiding? What dangers could be lurking in the dark spaces beyond?"

It was fun to wonder about such things.

The snapping scorpions, I thought, still looked more like angry octopi that were furiously kicking up debris as they trailed along surfaces, but hey--you can't win 'em all.

And I really liked the addition of swimming. It was a sparingly used element, sure, but still it added an interesting new dimension to the gameplay. Really, I just thought that it was a nice infusion of a gameplay element from the similarly-themed Jungle Hunt, which was one of my favorite Commodore 64 games.

At the time, I didn't know how to classify Pitfall II. It played a lot like the original Pitfall, certainly, yet, still, it clearly wasn't the same type of game. It was something different--something more "advanced." It was whatever you'd get if you took a side-scrolling platformer and expanded upon it by allowing for both horizontal and vertical movement and taking away all of the restraints (time limitations and lives). All I knew was that I was fascinated by how it worked. I'd never played anything like it; I'd never played a platformer that allowed me to move about and explore so freely. (In the future, and specifically after playing Metroid, I'd come to understand that these were the qualities of a "side-scrolling action-adventure" game.)

But even then, Pitfall II didn't abandon the series' classic conventions, no. It still required you to advance from screen to screen and do so while leaping over gaps, tactically evading obstructive critters, and procuring gold bars and other treasures in an effort to earn the highest-possible score (though, I wasn't yet sure if this was the only goal). The difference was that I now had the option to advance more meticulously rather than do what I was usually inclined to do: hyperactively and recklessly charge forward. (Of course, I still tended to do the latter.)

Weirdly, it took me a long time to notice that Pitfall II had completely ditched the original Pitfall's vine-swinging mechanic and the hazards that were most closely associated with it: obstructive water bodies, gators, and those expanding-and-contracting swamps. And because there was no vine-swinging, there was no Tarzan-yell sound effect, which was one of my favorite aspects of original Pitfall (though, thankfully, Harry's jumps still made that same iconic springing sound)! It must have been that I was so utterly entranced by all of the new things that Pitfall II was introducing--its curiously evocative main theme, its fascinatingly new gameplay style, and all of its new critter types--that I was simply unable to notice anything else.

Or maybe I was just generally unobservant.

I don't know.

Though, like I said, I was quite aware that Pitfall II was a different type of game. Its world was labyrinthine, and it contained many in the way of branching paths; some led to dead ends while others took you to new (but visually similar) sets of caverns, each of which had several branching paths of its own. And I was pretty confused by this type of level design; I never knew where I was or where I was going. Also, I didn't know what I was supposed to be doing. "Am I here merely to collect treasure, or am I meant to reach an unspecified endpoint?" I kept wondering as I was running through series of similar-looking caverns.

I suspected that it was the latter, and I did so because of something I saw on the game's opening screen: a tall brown-colored creature (which I originally identified as a kangaroo with restless-leg syndrome) who could be seen hanging out on the level below. My guess was that this creature wasn't a boss but rather a "final marker," and if I wanted to win, I'd have to travel over to the creature's location and engage with it some way. (I didn't realize until years later that this "kangaroo" was actually Harry's feline sidekick Quick Claw, who I'd seen in Saturday Supercade's Pitfall cartoon. He was a regular character. Though, I don't feel stupid about not immediately recognizing him because, I'll always argue, Pitfall II's interpretation of the character looks nothing like a bipedal feline!)

And because I was who I was, I of course spent a whole lot of time trying to find ways to reach the opening screen's bottom level in ways that didn't entail actually playing through the game. In each of my earliest sessions, I made an exhaustive effort to leap over the speedy mouse that patrolled and obstructed the second screen's lower level, which was adjacent to the opening screen's lower level. The speedy mouse (which I originally thought was an "advanced scorpion type") was obviously programmed to unfailingly deny entry to the tantalizingly close final destination, but still I was convinced that there had to be a way to successfully leap over him--that there had to exist some type of pixel-perfect maneuver that would allow me to cleanly sail over the mouse and easily reach the game's endpoint.

It would never work. Though, still, I continued to cling to the belief that leaping over the mouse was possible, and I'd never stop trying to do it. In fact, the act of "wasting several minutes attempting to leap over the speedy mouse" became a requisite aspect of my attempted Pitfall II play-throughs. If I didn't start the adventure by attempting to leap over that mouse, I'd essentially render the entire play-through invalid!

What made Pitfall II more inviting than its predecessor was the presence of checkpoints: When you collided with any enemy, you didn't die and lose one of a limited amount of lives, no; rather, the game would simply return you to the last checkpoint you activated! This was great for me because I tended to play recklessly, and having a checkpoint system made me feel less anxious about operating in such a manner! If the only punishment for foolishly attempting to pass under a descending frog was being slowly transported back a few screens, then I had it made! I was free to play as impulsively as I wanted! Though, still, I'd always feel a little sad whenever I was being sent back because of what would happen during the transition: My points would continuously drain, and a depressing-sounding version of the main theme would play. And so I couldn't help but get a bit pouty.

Generally I tried to avoid engaging with Pitfall II's terrifying assortment of enemies--its bats, birds, frogs and electric eels, all of which were lethal to the touch. My favorite tactic was to fall into vertical passages' topmost gaps and drop down and thus bypass several levels at a time. Doing this was an ideal alternative to slowly climbing down the ladders and consequently having to deftly maneuver past frogs and flying creatures (the only time I'd run into trouble was when I'd mistime my drop and collide with a bat or bird when it was currently in an unfavorable spawn cycle). And if the only downside was that I'd miss out on obtaining a couple of gold bars, then, well, it was a small price to pay. "Who needs all of those points anyway?" I'd think.

And I thought it was cool how Harry's slamming into the ground was communicated: The screen would shake, and you'd hear a loud, painful-sounding thud! It was worth falling down gaps just to witness the outcome!

Because I was completely oblivious, I didn't notice that slamming to the ground in that manner caused you to lose points (the game subtracts 100 points from your total each time you slam down). There was plenty of other stuff I didn't notice, either--in the game and in real life. Really, it would take too long to list all of it. So let me summarize by saying that I was basically the kid version of NintendoCapriSun, and thus I was lucky to survive past the age of 5.

So to today's kids, I have only one piece of advice: Pay attention to what's going on around you. If you don't, you'll wind up making Youtube videos in which you spend all of your time quoting old movies and singing songs about bathrooms.

But even though I had the benefit of checkpoints and a trusty collection of cheap tactics, Pitfall II eventually grew too difficult for any of that to matter. As I neared the game's final stretch (or what I believed to be the game's final stretch), there was nothing upon which I could rely to overcome its most recurrent obstacles: birds and bats that flew across the screen in wavy patterns. To successfully move past any flying creature, you had to study its movement-pattern and time it to where you were running beneath it right as it was ascending upward. This was difficult because the birds and bats' hitboxes were unforgivably wide, and even the slightest contact would doom you; the window was so very tiny.

I could competently advance past two or three flying creatures in a row, sure, but I'd have to strain to do it, and I'd be mentally taxed at the end. And this was a huge issue because the game's final stretch consisted of dozens of levels that were filled with flying menaces. It was a huge gauntlet, and I just couldn't endure it.

In my earliest sessions, simply figuring out how to reach the final stretch was a major challenge. At one point, I ran out of places to explore, and it seemed as though there was no obvious path forward. So I was stuck.

I discovered the solution by chance: As I was hanging out on a random cliff, thinking about ways to access the ladder that was hanging above the lake's lower-left portion, a blue balloon suddenly started to float by! That's when I learned about the game's most curious mechanic: balloon riding. If you jumped up and grabbed onto a floating balloon's string, the balloon would carry you up the huge chasm that comprised the area's center portion! And that was how you could gain access to other cliffs and thus whole new sections.

The weirdest part was that Juventino Rosas' Sobre las Olas would play whenever you were being carried by a balloon. Such an overly cheerful tune felt completely out of place in Pitfall II, whose music, to that point, had been somewhat somber in tone. Though, that's what made its inclusion interesting to me. I was struck by the idea of a game suddenly introducing an element that was totally out of step with everything else it was doing. I saw it as the game's way of sending me a cryptic message of some kind and challenging me to figure out what it meant.

In that moment, it made sense to throw caution to the wind and let that balloon take me where it may. "I have no idea where I'm supposed to be going," I thought, "so I might as well just fly up as high as I can go and have fun carelessly diving off random cliffs!"

My sense was that I needed to access the chasm's top cliff, but I couldn't get up to it because something would always go wrong. It was either that a pesky bat would fly by and pop my balloon or that I'd come in too fast and hit the chasm's ceiling before I could finish drifting over to the cliff's edge.

This area of the game always confused me, though. It had so many cliffs and so many branching routes that I'd quickly become lost whenever I attempted to explore it. Usually I'd just say "Screw it" and bypass most of the area; I'd simply fly up to the first cliff on the left and head directly to the game's final stretch.

And, like I said, that's where I'd hit a wall. I'd be unable to clear the game's final vertical section, which was stuffed with a ridiculous amount of wavily-flying birds and bats and comprised of a seemingly endless series of zigzagging platforms. Also, it contained no checkpoints (there was only one checkpoint to found in this area, and it was placed way at the bottom). So I was required to do it all in one go.

Though, the fact was that successfully evading a relentless stream of flying menaces demanded a type of patience and pixel-perfect precision that I was simply incapable of displaying. I just couldn't concentrate that long. Also, this level of repetition was too much for me; it was beyond anything I'd ever experienced in a game. And I just couldn't handle it. Constantly failing and having to restart from the area's lowest level and re-traverse the same 40-50 levels (or what seemed like 40 or 50 levels) over and over again was mentally exhausting. And inevitably I'd become so mentally fatigued and so frustrated that I'd start screwing up on even the earliest levels.

It's true that my facing these trials and tribulations helped me to evolve as a player. Undergoing these types of challenges helped me to sharpen my reflexes and understand how to read enemy movements (as long as said enemies weren't Medusa heads). Though, none of that really mattered because no amount of skill was going to help me to suppress my feelings of anxiousness and my impulsivity. Sooner or later, one of them was going to boil over and cause me to mistime an input. And then I'd have to start all over again.

The breaking point was when I finally managed to traverse my way to the top of the bird- and bat-infested hellscape and reach the area's final ladder. It was guarded by a single frog. This was good news because I never had much trouble working my way past the comparatively slow and easy-to-evade frogs. In the moment, though, I was so overcome with excitement that I prematurely pushed up on the joystick and wound up colliding with the frog just as it was landing from a jump. Then, painfully, I was sent back all of the way back to the checkpoint.

After that happened, I stared blankly at the screen for about 30 seconds, and then I proceeded to angrily exit the game and furiously storm out of my brother's room. And as I headed downstairs, into the den, I thought to myself, "There's no way in hell that I'm ever going to put myself through that again!"

That's what I promised myself.

And I held to that promise for 20 years--up until about a week ago, when I completed Pitfall II for the first time and did so for the sake of creating this piece. What I found is that it's nowhere near as long as I remember (it can be completed in about 13 minutes if you know what you're doing), and its final stretch isn't really that bad (it's comprised of only ten levels, and it takes about two minutes to clear it). It's a pretty manageable game.

That just goes to show you the type of power these games used to have over us and how we perceived them to be so much more than they actually were. Back then, I didn't see Pitfall II's world as a mere 80 screen's worth of simple brown platforms, no; rather, I saw it as an amazingly vast jungle that was formed from a seemingly endless series of lushly vegetated wooded areas, grand lakes, and dark caverns. It was an expansively large place and one in which I could get lost for hours and hours.

And, really, that's how I prefer to remember Pitfall II's world.

I knew that Pitfall II was released for other computers like the Atari 800 and the Apple II, and I wasn't surprised by that because, of course, Pitfall II was a "computer game." It made sense for it to appear on those platforms. But then I learned that my long-held conception of Pitfall II was wrong. It wasn't a computer-born game, no. It had a much different origin: It actually started its life on the Atari 2600! Then, later on, it was ported to various consoles and computers.

I was honestly shocked when I learned about this. I couldn't believe that the 2600 had played host to such a game. I didn't think that it had enough power. The whole time I was sampling it, I kept wondering, "How did Activision do this? How was it able to make such an advanced game on a platform whose technologically was so very limited?"

Amazingly it's the exact same game, and it contains all of the same content. Of course, it isn't quite as visually advanced as the other versions, no. Its cave and tree textures aren't as detailed, and it doesn't have as much color depth. Yet, still, it manages to look pretty damn similar to them. That's why I can't think of it as anything other than a technical marvel. It's probably the most technologically advanced game on the platform!

Impressively, Activision managed to stuff this entire game into a 12-kilobyte cartridge. And nothing's missing. It has everything the other versions have, including the music. Somehow, it has that entire main theme, note for note; it's a scratchier, bleepier version of the main theme, yeah, but still it's just as melodious as any other.

I can't even guess as to what type of wizardry was used to pull it all off.

Later on, I made another shocking discovery: Sometime in 1985, Pitfall II found its way to arcades!

This particular port was handled by Sega, which decided to get creative with the license. Its goal wasn't to alter the game's structure in any significant way, no, but rather to enhance the gameplay by adding in some new elements. It brought back mechanics and obstacles from the 2600 original (vine-swinging, obstructive water bodies, gator-hopping, and expanding-and-contracting swamps) and threw in a host of new things like bouncing logs, deadly pollen, falling apples, dual vines, crushing walls, a magma-spewing volcano, fireball- and arrow-spitting statues, falling icicles, and minecart sequences. And expectedly, the game's visuals and sound quality have been greatly enhanced.

This version has a three-minute time-limit, though that number isn't absolute. You can bump it up by obtaining treasure (when you obtain a treasure, the game adds 30 seconds to the timer). So if you want to stay alive, you have to explore and find treasure. If you attempt to speedrun your way through the game, instead, you'll surely run out of time and die.

After playing it for a while, I can say that arcade Pitfall II is a lovingly crafted homage to the game that inspired it and to the series in general. If you're a fan of either, you should definitely give it a look.

For me, though, the Commodore 64 version of Pitfall II: Lost Caverns will always be the definitive version. It's the one that shaped my world. It's the one that introduced me to a wonderfully new game type and laid the groundwork for a genre that would one day produce some of my most cherished favorites.

It was one of the most important games I ever played.

No comments:

Post a Comment