I adventurously scoured the desolate, unfamiliar streets in the continued search for my true self.

So Shadowgate turned out to be a revelation to me. It opened my eyes to the fact that I'd been missing out on something amazing. It showed me the power of point-and-click adventure games and how compelling, engrossing and inspiring they could be. It showed me that the gaming world was far more vast and wondrous than I originally thought.

Shadowgate changed my life. Its powerfully alluring aural, visual and textual qualities captured my imagination and thus stirred me to wander out from my comfort zone and curiously enter into unknown territory. I spent many months immersing myself in Shadowgate, and during that time, I learned a great deal about the point-and-click-adventure genre's intrinsic values and discovered that said values naturally appeal to me. I found that I was actually very fond of text-based adventures, which I'd previously dismissed because I'd determined that such games, based on what I'd seen from only two or three of them, were primitive, boring, and light on meaningful content.

I probably disregarded text-driven games because I wasn't much of a reader. At that point in my life, I preferred to spend my free time either drawing or creating elaborate constructions using the protective Styrofoam cases that I was taking from the boxes that contained my mother's most easily breakable valuables. I had an aptitude for writing, sure, but I didn't display it very often--partly because I felt that my grammatical skills were lacking and my vocabulary was too limited.

So basically my biases and personal insecurities drove me to avoid games and activities that were based around language.

But Shadowgate showed me the value of text-driven games. It showed me that language could be an amazing tool--that it could help a game to develop incredibly rich character and atmosphere and stir the imagination in unique and wonderful ways. That's what it did. It used its "advanced" literature to provide awe-inspiring character to its structures and inhabitants and create an amazingly wondrous atmosphere. And for that reason, I was captivated by it.

As a puzzle game, Shadowgate had limited replay value. Once you knew what to do, there was no real challenge to it. But as a language-based game, Shadowgate had endless replay value. It could always enchant you in wonderful ways. That's why I continued to eagerly revisit it. I returned to it often because I loved to observe and examine its highly evocative imagery; read its intriguingly written, imagination-stirring descriptions; and soak in its wonderfully unsettling atmosphere. I found all of its visual, aural, and atmospheric elements to be intoxicating. I couldn't get enough of them.

I'd return to Shadowgate not so much to play it but to instead feel it and draw inspiration from it. And I was content to continue doing that forever.

At the same time, though, I wanted more of what Shadowgate offered. I desired to play a game that expanded upon its ideas and provided me access to a similarly Gothic-flavored, imagination-stirring world. The problem was that I didn't know where I could find such a game. (Maniac Mansion was around, yeah, but its style was too goofy and its setting was too modern. Also, it lacked the Kemco-style menu presentation that I felt was an important part of the package.)

"Do Shadowgate-like games even exist?" I wondered.

But like I said: I didn't know anything about the MacVenture series. I'd never heard of it. So all I could do was assume that Shadowgate was a standalone game that was made specifically for the NES.

Over time, though, I started to become more aware of what was going on. Nintendo Power's slowly dripped bits of information began to clue me in to the existence of the much larger project that was being carried out.

The first hint appeared in Nintendo Power Volume 18's Pak Watch section, which unexpectedly revealed that yet another point-and-click-adventure game was on its way to the NES. I caught a glimpse of said game as I was turning to the section's first page, and immediately I knew what it was. Clearly it was a Shadowgate-type game!

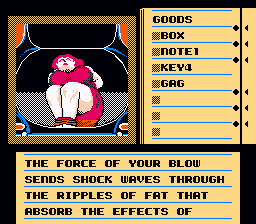

The lower-left corner's screenshot, which was the first thing I saw as I was turning to the page, told the entire story. Its imagery was unmistakable. The menus it displayed were identical to Shadowgate's. And that really excited me. I was thrilled to see the familiar-looking "Commands" list and table of "Goods"--both of which, desirably, were positioned and structured just like Shadowgate's (the only difference was that the Command menu's map panel was moved toward the center, which I thought was an unnecessary change)--because I knew what their appearance meant: a genuine Shadowgate-type game was on its way!

As my feelings of surprise and excitement subsided, I started to focus on preview's other content, and that's when I learned that the game in question was called "Deja Vu." It was a detective thriller.

Now, I didn't have any problem with detective stories, murder mysteries, police dramas, and the like, no. Rather, I enjoyed crime-fiction stories. They were always fun to watch. But the fact was that theirs just didn't represent the type of subject-matter that I wanted a Shadowgate-inspired game to explore. I was more interested in playing an adventure game that had a medieval-style setting; a cast that was comprised of monsters and supernatural beings; and architecture that spoke of a wondrous fantasy world. Deja Vu didn't have any of that; rather, it had a familiar-looking modern setting and a story that was grounded in reality. And that disappointed me.

I was still interested in playing Deja Vu, certainly, but because I wasn't particularly keen on its subject-matter, I didn't feel motivated to run out and buy it day one. "I can wait a few months to play this one," I thought.

Also, there was another factor working against Deja Vu: It was slated to be released in December of 1990--around the same time highly coveted games like Mega Man 3 and Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles II: The Arcade Game were scheduled to arrive. Because I was so obsessed with those games, I just didn't have any energy to devote to thinking about Deja Vu.

Though, I started to warm up to Deja Vu's ideas as I read through Nintendo Power Volume 20's big Deja Vu feature piece, which provided a detailed explanation of the game's plot. It seemed that our unnamed detective was an amnesia victim who was allegedly being frame for murder, and his story was taking place in the 1940s!

The piece had some interesting information about the detective's dire prognosis and his urgent mission to discover his true identity, but what really caught my attention were its screenshots and the imagery they displayed: the vacated exterior of "Joe's Bar," which had an old Ford Deluxe (a "gangster car," as I called it) parked in front of it; the curiously empty casino; and the mysterious and threatening silhouetted figure that could be seen through the window of an office door. I was so intrigued by them because I loved what they inferred. They evoked images of a man engaging in clandestine, undetected activity and working in isolation. And the idea of operating in that manner was exciting to me; it helped to make Deja Vu's premise seem so much more compelling.

I made sure not to read too far into the piece or look at any of the other screenshots because I didn't want any other parts of the game spoiled for me. And the moment I was done reading, I decided that Deja Vu was the type of game that I needed to play as soon as possible.

So on a cold January day in 1991, I went out and purchased myself a copy of Deja Vu--my third point-and-click-style adventure game and what I was certain wouldn't be my last point-and-click-style adventure game.

Unfortunately, I don't remember much about my first Deja Vu play-through or how, exactly, it played out. All I remember are my initial thoughts and impressions and some specific troubles that I faced.

I recall, for instance, how concerned I was about the fact that the cursor moved much more slowly than it did Shadowgate. The cursor's slower speed served to make some actions take longer than necessary, and I was worried that its sluggishness would cost me dearly in situations in which I was required to quickly move to a target or access the menus.

Though, my feelings of worry largely dissipated when I learned that Deja Vu was a more leisurely paced game. It didn't require speedy action. And it didn't have a time-constraint element, so I wouldn't have to deal with "Your torch is running out!"-type problems or worry about having to constantly track down preservation items. I could relax, think through my actions, and take the time to soak in the game's sights, sounds and atmosphere. And to me, that was a big plus. It meant that I didn't have to rush through the game and miss out on reading all of its descriptions and enjoying all of its little atmospheric touches. Rather, I could play at my own pace and take the time to savor the experience.

That's exactly the way in which I wanted to play adventure games.

In Deja Vu, I learned immediately, you had to do more work than you did in Shadowgate. You had to be much more thorough in your investigation. You had to operate with the understanding that even the most inconspicuous coat pockets could contain vitally important items like coins and bullets. You had to fully examine every part of every object.

Right from the start, Deja Vu tested the limits of my cognizance. It tried to misdirect me. It used the startling image of corpse to take my focus away from the mundane wooden desk on which the corpse was resting. And its trick worked. I failed to notice the desk, which was filled with important items, until much later on. That's how it went in the early going: I kept running into dead ends as a result of my failing to make simple observations. And I didn't start finding success until I changed my thinking and made it a point to notice my surroundings and treat every item and object as suspect.

What I liked about Deja Vu was that its puzzles were built on logic. They weren't, like many of Shadowgate's, opaque or arcane (which is to say that they didn't ask you to do inexplicable things like "opening" a coverless bucket and using a wand to turn a ceramic snake into a staff). So whenever I ran into a dead end, I knew that I'd done so because I missed something simple; it wasn't because I failed to yell "Alakazam!" at a water cooler.

Deja Vu had clear, understandable rules, and I was comforted by that fact.

What I didn't appreciate was Deja Vu's propensity for becoming unbeatable under certain conditions. It had a concerning number of fail states. If you ran out of coins, for instance, you'd no longer be able to buy a taxi ride, and consequently you'd permanently lose access to all of the game's other areas. You'd be screwed.

The thought of running out of coins constantly weighed on me, and at times it curbed my ambition to explore beyond Peoria, the game's starting area. (I might have felt less nervous about the possibility of running out of coins had I known that the casino's slot machine was programmed to pay out when you were down to your last coin. And I didn't learn until later on that the yellow taxi's driver would give you a break if you couldn't afford to pay the fare. He'd just let you leave. I wouldn't have known about that because I was too afraid that I'd get arrested if I tried to hop out of the taxi without paying.)

Also, I was annoyed to learn, you could only foil the gun-toting mugger's holdup attempts three times. Thereafter, any defensive act would prompt him to fire his gun and kill you. "Why do that?" I wondered. "Why put me in a position in which I can no longer do anything to stop him?"

It just felt spiteful. It was as if the game was punishing for merely moving around too much.

I didn't worry about this scenario quite as much as I did the former because the mugger's appearances were random and there was always the chance that he'd never show up over the course of the game, but still I was always concerned about the possibility of it occurring.

So yeah--Deja Vu had a few troublesome gameplay aspects.

To tell you the truth, I didn't have much of a clue as to what was actually going on in Deja Vu. Its overarching story was completely lost on me. I didn't pick up any of it. The whole time, I knew only of Ace's plot thread--of his struggle to regain his memory and clear his name (apparently he was being framed for a crime).

Over the course of the game, there were mentions of "Siegels," "Sternwoods" and "Sugar Shacks," but I had no idea who those people were or how, exactly, they figured into the story (and for a while, I thought that "Sugar Shack" was a place--maybe a candy store, a bar, or some other type of business establishment). I was aware that some nasty forger was going around planting incriminating evidence everywhere and doing his or her best to paint Ace as a murderer, yeah, but that's about as far as my understanding stretched. I never caught on to the fact that it was all part of a complex plot. The only thing I knew was that Ace was on a mission to regain his memory and prove that he wasn't connected to whatever crime had been committed.

And at the time, that was all I needed to know. The rest of it didn't matter to me. I wasn't particularly invested in the story, and I didn't care about any of the characters. The only thing that really interested me was the game's world. I found it to be amazingly intriguing. I loved to observe it, examine it, and think about the messages it was conveying. I enjoyed immersing myself in its silently dangerous environments and imagining what they'd look like in real life. I liked to listen to the music and let it shape my conceptions and daydreams.

Years later, I learned that the game's events were supposed to be occurring during the late-night hours, but because the NES' palette was more limited than your average computer's, said events had to be presented as though they were occurring during the day. And I was happy that it worked out that way. The daytime setting was more fitting, I thought. It provided the game a more alluring atmosphere. It evoked some very stirring images.

The scene I always loved to picture was one of quiet afternoon Sunday during which everyone was home and recovering from the workweek and content to hang around and watch TV all day and essentially leave the whole world to me and allow me to treat it as my own personal playground.

That, I believed, was the best setting for a game like Deja Vu.

Deja Vu, as I hoped it would, did a great job of evoking feelings of desolation. Very often, it would season a room's description with a characterizing statement like "no one's around" or "you can't see anybody." And thus it would make me feel as though my activities were occurring in total secret. I was a ninja operating in the shadows. No one knew where I was or what I was doing. And that's exactly how I wanted it to be.

My favorite room was the interior of Joe's Bar's, whose imagery and music did more than any other's to symbolize Deja Vu's remote-feeling atmosphere. When you entered the bar's main area, the music would shift from the rather-optimistic-sounding Ace Harding theme (whose intro, I was excited to realize, was a note-for-note recreation of Shadowgate's flute jingle) to a strangely mysterious, eyebrow-lowering tune that worked to evoke images of an investigative man curiously moving about a quiet, creaky room whose only source of illumination was refracted sunlight--the type that provided the room a muted brightness that dimly outlined all of its structures and revealed all of its floating dust particles. And this man could only see the outside world through a large window that provided a static view of the deserted, heat-drenched streets on which no potential witnesses would be wandering on this day.

The bar interior was the game's most evocative environment. Whenever I'd visit it, I'd take the time to examine and think about its imagery, soak in its tune's every character-imbuing note, and imagine what it'd be like to be in that place.

Because I wasn't sure what, exactly, I was trying to prove or which of my inventory items were most incriminating, I relied mostly on the built-in fail-safe that prevented you from discarding necessary items. If the game wouldn't let me dump an item into the sewer water, then I knew that it was key to helping me regain my memory or clear my name!

Really, though, it's kind of sad that I couldn't even deduce that the people sleeping in the Auburn mansion's beds were the game's actual villains. I assumed, rather, that they were two dead people and that they were killed because they were unfortunately got caught up in the true villain's scheme. But it turned out that they were just really heavy sleepers. I discovered this years later when, on a whim, I used Sodium Pentothal capsules on them and watched on, with a shocked expression, as they woke up and started talking and then proceeded to admit that they were behind the frame-job. (I didn't suspect that they were villainous because they were average-looking people. My assumption was that the game's story was "typical gangster stuff" and that consequently its unseen antagonist had to be your standard fedora-wearing, Tommy Gun-waving 1940s mobster.)

I didn't fully piece together what was happening in Deja Vu until years later, when I became more observant and more willing to sincerely engage with its material. Basically I stopped playing it like it was Shadowgate. I stopped trying to solve puzzles via experimentation and trial-and-error processes, and instead I took the time to attentively read documents, think about what words actually meant, gain an understanding of the characters and their motivations, and put my reasoning and deductive skills to use.

And that's when I figured out what was going on in Deja Vu: Ace Harding had been framed for murder by John Sternwood and Martha Vickers, who had entered into a secret relationship. Their framing of Ace was one part of their complex plot to extort and then kill their current lovers and make it appear as though others were responsible for these crimes!

So yeah--the story was a lot heavier than I originally thought.

But as I've been saying: A lot of that stuff happened later on, when I began playing Deja Vu regularly. Early on, I didn't play it all that much. I stayed away from it because it wasn't as good as Shadowgate, which was a world-changing game for me. It didn't have the same power. Its subject-matter just wasn't as compelling. Case files, hitmen and casinos didn't excite me as much as magic scrolls, wyverns and moonlit courtyards.

So I decided that Deja Vu just wasn't what I was looking for. It didn't have the type of world I wanted to explore. So I only played through it a handful of times in that first year.

But even then, Deja Vu still managed to stand out among the dozens of games in my respective game libraries. There really wasn't much else like it on the NES or the Commodore 64 (well, as far as I knew). There weren't many games that could stir my imagination in the same way--inspire me to wonder about what it would be like to inhabit its spaces and operate within them. Deja Vu wasn't as powerful as Shadowgate, no, but still it succeeded in creating an interesting, alluring world and making me feel as though I was the center of it.

But when I finally evolved a bit and began to expand my interests, I returned to Deja Vu and found new enjoyment in playing it. I gained a fondness for its style of storytelling. And then I started playing it regularly. Sometimes I even played it with friends!

And as did many of the games I played with friends, Deja Vu wound up gaining lasting power for ridiculous reasons. The first was our fondness for the game's randomly appearing mugger (of all characters). We found great amusement in his behaviors. We thought it was hilarious how he'd show up each time sporting a new facial wound that he suffered as a result of the jab we previously pumped into his face, and because we weren't convinced that the game's three-repelling-strikes rule was absolute, we were always trying to find ways to inflict further injury upon him and prompt new funny dialogue. We'd try to bop him with our frying pans and sausage links, and we'd attempt to use the environment's objects as weapons against him. But none of it ever worked; invariably he'd evade our attacks and shoot us.

We were always tickled by our characterization of the mugger and what we imagined his temperament and line-delivery to be like. Our conception was that he was a ninja-like speed freak who would pop up from out of nowhere and shout "Give me allllll your money!" in a voice that sounded a lot like the Wicked Witch of the West's. And he'd respond to a thwarted holdup attempt by running down the street with his arms flailing wildly and do so while yelling "I'llllll be baaaaaack!" in the same exaggerated manner.

We further emblemized the mugger by doing for him what we did for all of the characters we ironically celebrated: We incorporated him into our outside-world projects and silly activities. The first thing we did was make him part of our "Master Criminals" series (a card series that was comprised of newspaper images that we cut out after we scribbled on them and turned their human subjects into wacky-criminal characters), in which we depicted him as a stretchy-armed buffoon who would try to hold up his victims from extremely long distances.

Then we made him a recurring character in our live-action home version of Law of the West (which I talk about in detail in my Law of the West piece). And because we liked him so much, we even gave him a special attribute: If he lunged forward while bellowing "Give me allllll your money!", he'd gain the ability to steal one of the sheriff's prizes! And like it was in Deja Vu, his act of thievery could only be thwarted with a quick jab rather than a rifle shot, which, comparably, took too much time to execute. If the jab connected in time--if it struck him before he could grab a prize--he'd be forced to flee, and he'd necessarily have to holler "I'llllll be baaaaaack!" while exiting.

And naturally we saw to it that the mugger appeared several times per game.

At some point, the mugger gained another special ability: shapeshifting. He could assume the form of any other character and do so with the intention of lulling you to sleep and setting you up for a surprise lunge. And because he was exempt from the rules that governed scene progression, he was able to reveal himself and subsequently lunge forward at any time--during his entrance, in the middle of a dialogue exchange, or while he was exiting. So in our version of the game, you had to stay alert at all times.

Unfortunately for the mugger, though, his character was eventually forced into retirement. This happened because he was supplanted by one of our newly created characters: Dink, who was an amalgamation of the hooded thieves from Golden Axe, this very same mugger (who thus became redundant), and current New York mayor David Dinkins (if you want to know the specifics of how Dink came to be, please read my Golden Axe piece).

But the mugger wasn't the only character we enjoyed interacting with and caricaturing, no. We were also fond of the horribly misshapen bum, who would pop up every now and then and offer to give us advice. Each time he appeared, our response, naturally, was to punch him in the face. We'd strike him because doing so produced what we thought was the game's funniest line: "I doubt he felt it!" (To us, there was something hilarious about the idea of a guy being so intoxicated or drugged out that he'd somehow gain the ability to absorb and completely no-sell haymakers. We'd imagine a dopey-looking fellow getting belted and then just standing there with the same blank expression on his face and acting like nothing had ever happened.)

We never realized that it was a misattributed line. In actuality, it was the line that would prompt whenever you'd pump a jab into the gut of the grossly obese Ms. Sternwood, who was lying unconscious in a trunk. "I doubt she felt it!" the line would say. (When you're a kid, it's natural that the first thing you do when you see a fat person in a video game is to run up to him or her and start pumping jabs into his or her gut.)

The actual line was "...he may not have even noticed it," but we somehow never made that observation. Instead we continued to operate as though it was the former.

"I doubt he felt it!" became another one of our oft-repeated inside jokes. We'd repeat it to each other any time we'd see or imagine a scene in which a drunkard or an obese person (like the odious Sr. Ginetta, who was one our meanest teachers and someone we frequently mocked) was punched in the face. And over time, the line slowly evolved into the goofier, more obfuscated "I doubted he felted it!", which we thought was a super-hilarious variant that needed to be repeated constantly.

Because obviously we were mentally stunted.

Over the years, Deja Vu remained a great source of entertainment for my friends and I. We are able to extract enjoyment from it in many different ways. We had fun with it by (a) simply playing through it and enjoying its gameplay and story elements, (b) immersing ourselves in its quietly mysterious world and having deep discussions about its alluring environmental and atmospheric qualities, (c) interacting with and mocking its freaky characters, and (d), of course, finding new and interesting ways to commit suicide (which is something you have to do in an adventure game if you truly want to get the full experience)!

Deja Vu was our least-favorite of the three NES MacVenture games (we didn't think that it was quite as good as Shadowgate or Uninvited), yeah, but still we considered it to be a great point-and-click-adventure game and an equally important part of our group culture. And it, too, stayed with us until the very end.

These days, I'm seeking to delve deeper into Deja Vu's world by discovering and playing all of the other versions of the game (some of which bear the subtitle "A Nightmare Comes True!"). Deja Vu is also available on the Apple Macintosh, the Apple II, the Commodore 64, the Amiga, the Atari ST, the Windows PC, and a few other platforms, and I'm looking forward to playing through all of its variants and talking about them on this blog!

(I would have been able to explore more of Ace Harding's world back in the early 90s had Deja Vu II: Lost in Vegas come to the NES as planned. Unfortunately it never arrived. It was canceled for an unknown reason. And because Nintendo Power never mentioned the cancellation, I continued searching for the game for many months. I kept running all around the state looking for a product that didn't exist. About 9 years later, the canceled NES version was revived and packaged with the original NES Deja Vu in a special Game Boy Color compilation called Deja Vu I & II: The Casebooks of Ace Harding, and when I started getting heavy into Game Boy emulation in the early 2000s, I made sure to seek it out and play it and take the time to thoroughly explore it.)

So in the end, Deja Vu made a big impact on me. It shaped my world in a significant way. It might not have been the game that I was looking for in 1990, but it was certainly the game that I needed at the time. It taught me a lot about adventure games. It showed me how truly diverse the genre was and gave me a sense of what I was sadly missing. And ultimately it inspired me to open my mind and bravely journey into a much larger universe.

That journey was filled with moments of hesitancy and many other tough mental challenges, but I took it on with courage, and consequently I emerged as a seasoned adventurer. And I could thank Ace Harding for providing me the tools I needed to successfully navigate my way around this wonderful new place.

Did you ever get around to the sequel? I know it came out on the GBC at some point.

ReplyDeleteI played it sometime in the early 2000s.

DeleteI wanted to talk about that experience in this piece, but I just couldn't fit it in anywhere (not naturally, at least). Though, your comment has me thinking that I shouldn't avoid mentioning that I've played the game. So I think I'll expand the parenthetical paragraph to include a bit about having played it.

Thanks for inspiring the update!