Conquering Mega Man's pint-sized platformer required not only an increase in gaming skill but also some emotional growth.

So as I explained in my Metroid II: Return of Samus piece: During my early Game Boy years, I bitterly held to the biased view that a portable game system simply wasn't the place for sequels to big-name NES games. My opinion was that portable games were, by their very nature, lesser creations and consequently unworthy of finding inclusion in franchises that were associated with technologically superior platforms like the NES.

As far as I was concerned, any Game Boy game that carried the title of a popular NES series was doing so fraudulently. It wasn't a real entry in the series. It was related to it in name only, and thus it had no place in the official canon!

I had nothing against the Game Boy, itself, no. I thought it was great. I loved owning it. It had enriched my life and provided me the amazing gift of being able to have great gaming experiences both on the road and from anywhere in my home. It was one of my favorite platforms.

Yet still, I couldn't see the Game Boy as anything other than a subordinate device. I'd determined that it was technologically inferior to all current 8-bit platforms and thus only good for puzzle games and simple platformers. And as that logic dictated, it was absolutely no place for sequels to standout NES games whose most important qualities were their dense, colorful visuals; large environments; and high-quality tunes.

It wasn't hard for me to find the evidence that I needed to confirm my belief. I didn't have to look any further than the preview images for Double Dragon II and the Shadowgate-inspired Sword of Hope. They told me the whole story. They spoke of games whose visuals were compressed- and anemic-looking--of games whose visuals couldn't come close to meeting the standard of excellence that was set by their NES analogs'. And all I could do was conclude that the Game Boy and big-name NES franchises were a poor match.

That's why I dreaded to think that platform-hopping would become a trend. I didn't want to live in a world in which sequels would become less than what they could have been!

I'd felt that way ever since Nintendo Power Volume 26 arrived at my house with the horribly awful news that the Metroid series would be the first to make the jump. To say that I was angry about that situation would be an understatement.

But then Mega Man came along and destroyed that assumption. It showed me that Game Boy games could actually look the part! Its character sprites said it all; they were directly comparable to the NES games'! And I found that to be pretty astonishing.

At the same time, though, I couldn't ignore that the screenshot was also conveying an air of disappointing compromise. Mega Man, for however authentic it looked, was still a Game Boy game, and thus it had repellent qualities like low screen resolution and a lack of color (vibrant colors were, I felt, a vitally important element of Mega Man games). And that prevented me from having any real interest in it. Not even Nintendo Power Volume 27's enthusiastic multi-page preview and recycled Mega Man 3 artwork, for which I had a great fondness, could convince me that the game (whose official title was Mega Man: Dr. Wily's Revenge) was worth anything more than a quick sampling.

In the months that followed, I mostly ignored the game's existence and continued to argue that Game Boy sequels simply weren't worth serious attention. "There's no way that a colorless, cramped-looking series entry could ever live up to the standard set by all-time classics like Mega Man 2 and Mega Man 3, both of which were the product of the NES' superior technology and the type of developer ambition that only said technology could inspire!" I debated to no present opposition.

And, well, if you've read my Metroid II piece, you know that my view eventually changed. In late 1991, Samus Aran's portable adventure blasted its way into my life and proceeded to shatter the shield of ignorance that I'd been stubbornly projecting for years. It completely altered my perception of the Game Boy. It helped me to see that Nintendo's little gray brick was actually capable of rendering large-scale worlds and delivering console-quality experiences. It showed me that the Game Boy had way more potential than I'd thought!

And my coming to accept the Game Boy as a console-equivalent platform couldn't have happened at a better time. It occurred during a period in which I was facing a crisis: It was only two months into 1992, and already I'd become bored with all of my Christmas games! I was in desperate need of something new! This was a time in my life when I was developing a deep passion for the medium; it was a period in which games had become my only sustenance and I was constantly in need of nourishment! The problem was that neither the NES or SNES had anything interesting on its currently-available game list (the SNES was in a slow period, and the NES' game list was comprised largely of junk).

But now I had a solution to my problem: The Game Boy's library had since become packed with console-level games, all of which I'd previously ignored or dismissed, and thus there was a ton of great content for me to purchase and enjoy!

And because I was, at the same time, still at the height of my Mega Man fandom, you had the perfect set of circumstances for me to exuberantly commit to a largely blind purchase of Mega Man: Dr. Wily's Revenge!

I was ready to make the game my own and excitedly tear into it!

Unfortunately, though, there was a big obstacle to that purchase--a serious problem that had suddenly developed: Because I'd recently blown all of my Christmas money on Mega Man 4 and some less-than-quality NES legacy games, I didn't have the funds necessary to buy the Dr. Wily's Revenge!

But because my emotions were running so high, I wasn't prepared to give up on the idea of buying the game. I was determined to find a way around the problem. "I need to own Dr. Wily's Revenge," I thought to myself, "and I need to own it now!"

I only had around $20 in cash, which wasn't nearly enough to buy the game, but still I begged my mother to drive me to Toys R Us the next day. I did so with the belief that I'd come up with a solution to my money problem in the meantime.

When I finally calmed down, I began to realize that there was no practical solution to my problem, and immediately I went into panic mode. In my desperation, I resorted to a tactic that had proven successful in the past: I went down to the basement at a time when my brother, James, was out with his friends (the basement was his domain, and usually he wouldn't let me come down there) and began digging through the couches for loose change! James' absent-minded (and otherwise inebriated) friends were always unwittingly dropping their money into the couch cushions after engaging in one of their many night-long Poker sessions, and usually I was the beneficiary of their carelessness.

My expectation was that I'd dig up two or three dollars and get a little closer to the magic $40 mark. And somehow, amazingly, I came pretty close to reaching that total! (Seriously--what was it with these guys? Either their pants pockets were in serious need of stitching or my brother had successfully executed a genius get-rich-quick scheme that entailed hiding magnets beneath the couch cushions.)

But I didn't come close enough. I was still short a few dollars, and I couldn't think of any other way to scrounge up money.

Over the next few hours, I grew increasingly distressed, and when I reached my most desperate point, I made one of the poorest decisions of my young life. I determined that the best way to get a hold of the cash I needed was to head over the place where it was available in abundance: in James' room. In the cabinet above his Commodore 64, I knew, he kept a not-so-well-hidden glass jar that was filled with money.

When the coast was clear--after James returned to the basement to be with his friends and my parents and company moved over the dining room--I sneaked upstairs and into James' room and took some dollar bills out of the glass jar. And just like that, I'd arrived at a total of $40! I told myself that I wasn't "stealing" the money but instead "borrowing" it. "After all," I thought, "I plan to return the money after I replenish my funds!"

I mean, it wasn't like James would notice that the money was missing. He was never the observant type. "So, really, what's the harm in taking it?" I rationalized.

Well, there was plenty of harm, I learned. Mainly, a never-before-experienced strain of anxiety swelled within me in the following hours. Suddenly, I started feeling as though a dark specter had invaded my consciousness and was now controlling my thoughts. I'd become possessed by an unidentifiable scourge that was intent on endlessly bombarding me with unwanted mental images and memories of my money-"borrowing" scheme, which I'd been trying to put out of mind. This dark entity's relentless prodding made it difficult for me to concentrate on anything else or even breathe normally.

I couldn't overwhelm these images or flashbacks with positive thoughts, and trying to block them out, I found, only boosted their resolve to haunt me.

The feeling that had overcome me was uniquely awful. It was stressful and oppressive. It was emotionally crippling. It made it impossible for me to function normally.

It was the feeling of guilt.

I had, like I said, never dealt with such a feeling. I didn't know what it was. I didn't know how to handle it. All I knew was that I hated what it was doing to me. It was ceaselessly gnawing away at my conscience and causing me great anguish.

As the hours dropped off, the guilt grew. It became increasingly unbearable, and before long, it wholly consumed me. And eventually I reached a breaking point--a moment in which I could no longer fight my feelings. That's when it became clear to me that there was only one thing I could do rid myself of the dark specter: put the money back and admit to the fact that nothing in this world--not even a glorious new Mega Man game--was worth that kind of emotional suffering. So that's what I did.

I've spoken many times in the past about how my video-game experiences have served to teach me some very valuable lessons, but it was always the case that said lessons were relative to the games, themselves. They influenced how I felt about gaming, not life. But that's not how it was here. This experience, in contrast to all of the others, taught me an important life lesson. It taught me that stealing wasn't excusable and that engaging in such an activity would only result in your becoming filled with inescapable, crushing guilt.

The guilt that I was feeling on that day was ravaging, and I knew that I never wanted to experience anything like it ever again. Consequently, I vowed to never again steal anything from anyone. It's a rotten thing to do, I learned, especially when your victim is someone who has always been noting but generous to you.

And in the end, I decided upon a better solution: I made a deal with my mother and promised her that if she'd agree to cover the remaining dollar amount, I'd pay her back just as soon as I got a hold of some money.

So on the following day, she drove me over to Toys R Us, and I picked myself up a copy of Mega Man: Dr. Wily's Revenge!

Sadly, I have no chronological memory of my first Wily's Revenge experience. I don't recall the order in which I tackled stages or the ways in which I experimented with the Robot Master weapons and discovered enemy weaknesses. The only thing I remember is the immediate impression the game made on me. It was mostly a negative one. I had a lot of problems with the game.

For starters, I was bothered by the fact that I couldn't locate the words "Dr. Wily's Revenge" anywhere on the title screen. I perceived their absence as an inexplicable omission. "It says 'Dr. Wily's Revenge' right there on the box's front cover," I observed, "so why is that subtitle missing from the title screen?!"

It didn't make any sense to me.

I looked for an explanation in the manual, but I wasn't able to find one. There was nothing in the story synopsis that suggested that Wily was behaving any differently than normal. There was no such context in the game, either. Nothing I was seeing on the Robot Master-select screen or beyond was convincing me that a "revenge" plot was in effect. The action was simply about traversing themed stages and battling Robot Masters--business as usual in Mega Man Land.

I wondered about the nature of this odd disconnect and if it said anything about the amount of care and effort that was put into the game's creation. "Were the developers neglectful or unmotivated?" I questioned. "Or were they deceitfully using an interesting-sounding subtitle to trick people into thinking that their game wasn't entirely formulaic?" (The truth, I learned much later on, was that the game didn't really have a subtitle. Said subtitle only appeared on the box cover. It was placed there by Capcom's localization team, which used it to clearly communicate to customers that the game wasn't a port of the original NES Mega Man. At the time, I didn't even know what "localization was!)

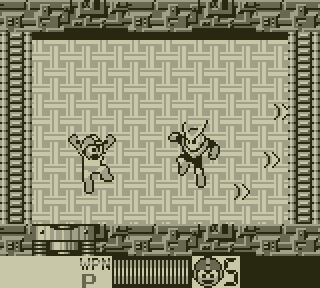

Wily's Revenge, expectedly, looked pretty damn good for a Game Boy game. Its character sprites and backgrounds were highly detailed and easily decipherable (whereas Game Boy games usually featured small, pixelated characters and sparsely decorated backgrounds), and overall its visuals were sharp, clean and vibrant. It did, as its Nintendo Power preview imagery promised, look just like an NES Mega Man game!

But unfortunately that faithfulness came with a price. It created the conditions for a considerably off-putting gameplay element: cramped level design! And that didn't surprise me. It was something that I became immediately concerned about the moment I saw Nintendo Power Volume 23's preview image.

I mean, I appreciated the large, authentically recreated classic Mega Man sprites, yes, but I couldn't ignore the problem that such authenticity created. The stages' vertical resolution was simply too small to accommodate NES-sized sprites! It was too restrictive.

What frustrated me most was that the level designers frequently leaned into that limitation and designed platforming challenges around it. There were so many instances of tight jumps that had to be made within extremely narrow passages. While attempting to make such jumps, I'd routinely hit my head on low-hanging ceilings and resultantly fall into spike beds or death pits. It was such an obnoxious design choice.

"What kind of nasty trick is that?" I'd whine each time I bonked my head and fell to my death. "Isn't this game already tough enough without garbage like pixel-perfect jumps?!"

Other Mega Man games similar close-quarter jumps, sure, but none of those jumps were ever mandatory, and they never had as much riding on their completion. Checkpoints were very rare in Wily's Revenge, and thus failing those jumps imposed a huge penalty on the player. Oftentimes, the consequence was having to repeat the entire stage!

"Why did they consciously choose to design stages this way?!" I repeatedly questioned in an angry way. "Wouldn't it have been better for them to instead increase the stage environments' vertical length and have the screen scroll up and down?!"

Wily's Revenge's pixel-perfect jumps weren't what I'd call "hard," no. They were just cruel.

Also, I felt as though the controls and mechanics had taken a hit. Mega Man's movements were sluggish and laggy, and I thought it was weird how his Mega Buster pellets were uncharacteristically round and traveled across the screen at a much slower rate than the NES-games' pellets. To me, smooth controls and blistering, rapid pellet-fire were important elements of Mega Man games, and sadly both were missing here.

The result was gameplay that had a slower pace and an increased gravity. And when you stacked on the cramped level design, you were left with a game that had, from what I'd seen, a disappointing lack of fun aerial challenges. As I played on, I remained concerned that these elements would continue to cause the action to stay largely grounded. I was afraid that I'd be forced to spend the majority of my time standing in place and battling nothing but hordes of stationary screw bombers and those fuzzy, aggravating saw-blade enemies.

Additionally, I wasn't a fan of the HUD changes. I didn't like that Mega Man's health meter was 2/3rds of what it was in the NES games. The contrastingly meager 19 health slivers seemed insufficient in a game in which enemies and their attacks inflicted heavy amounts of damage. Having less health meant that I'd have proceed cautiously and thus refrain from doing what I played Mega Man games to do: go fast and engage in run-and-gun-style action! It was too dangerous to that in Dr. Wily's Revenge, and consequently the run-and-gun aspect was greatly diminished.

The other problem was that Dr. Wily's Revenge was stingy when it came to health drops. They were very rare. I mean, it was nice that large energy pellets replenished half of Mega Man's health, sure, but enemies would almost never drop them! So there was no point in trying to farm them. "This game simply doesn't want me to be in a healthy state," I felt.

I was annoyed by these design decisions. "Why couldn't they have made the energy and weapon meters smaller and longer and simply arrange them vertically?" I complained. "Is this their way of unnecessarily making the health system reflect the game's cramped, 'portable' nature?"

During my earliest experiences with the game, I spent an inordinate amount of time wondering why the developers made the decisions that they did. I was baffled my most of what they did.

While I was disappointed that Guts Man and Bomb Man didn't make it into the game, I very much understood why they were absent: There would be no room for them maneuver and operate! In order for them to find inclusion, I realized, they'd have to be changed in undesirable ways. The designers would have had to shrink Gut's Man's boulders down to a tiny size, lest they'd fill half the room and become impossible to dodge, and by doing that, they'd diminish what made Guts Man intimidating. And they would have had to made Bomb Man less hyperactive and reduce his bombs' splash damage, which, likewise, would severely downgrade his offensive capabilities. Neither character would translate well to the Game Boy format, so it was best that they were both absent.

Still, though, I couldn't help but feel that their omission was just another in a long line of diminishing compromises and concessions. It, like all others, served to make Dr. Wily's Revenge feel like a bad CliffNotes version of a classic game.

And then there was the worst part of the package: the ridiculous difficulty! Dr. Wily's Revenge, I was finding, was the series' most challenging game by a significant margin. Its stages, in particular, were punishingly difficult, and you didn't so much as traverse them as you did endure them. They constantly evoked feelings of stress and demanded that you move about in a restrained way. And consequently the game lacked a fun factor.

And though the game looked great, it was clearly too graphically ambitious for its own good. Oftentimes it'd throw out more sprites and objects that the Game Boy could actually handle, and its doing so would always result in massive slowdown. Even simple animations would induce serious processor strain. Mega Man's damage frames, for instance, would cause the action to lag horrendously. And said slowdown would always be accompanied by a large amount sprite-flicker.

These issues were hard to ignore.

Now, it's not that I didn't appreciate the developers' ambition, no. I certainly did! It was just that I couldn't deny that it came with a cost.

After owning the game for a couple of months, though, I came to see its technical achievements in a new light. I'd arrived at a point in which I was able to fairly assess what it was doing and look past the adverse consequences of its authenticity-focused design aspects and recognize that it was a solidly crafted game. It had processing issues, yeah, but none of them were really as diminishing as I'd originally determined. In truth, it ran really well!

And once I accepted that issues like slowdown and sprite-flicking were simply unavoidable in graphically impressive Game Boy games, I could give Dr. Wily's Revenge its due and admire its ambition to look as similar to the NES games as possible. No other NES-to-Game Boy series had ever produced a game that came that close to its NES siblings visually. Dr. Wily's Revenge was as faithful as possible, and that meant a lot to me. Its sprite-work was impeccable, its textures were sharp and clean-looking, and its background work was fantastic--even when it was minimalistic in nature (I loved, in particular, the mountains that appeared in Ice Man's stage; they were simply rendered, yeah, but still they were visually interesting, and they stood among the most powerfully imagination-stirring images I'd ever seen in a game).

Sure--the game's palette limitations made it appear as though Mega Man was sporting a five o'clock shadow, but that didn't bother me, no. Rather, I saw it as a positive quality--as one of those little details that (much like the Mega Buster's round pellet shots) helped the game to create its own personality!

But the best part of Dr. Wily's Revenge, I felt even during my earliest experiences with it, was the soundtrack. It was superb! The music's composer, to his or her great credit, wasn't content to simply recycle the original Mega Man's tunes, no; rather, he or she decided to instead recreate the tunes from scratch and in the process spice them up and embellish them with elaborate intros and more-energetic-sounding instrumentation. And the result was tunes that were more spirited and more invigorating in character.

My favorite tune was, by far, the one that played during Elec Man's stage. It was a beautifully recreated piece. It was enhanced greatly by its additions and refinements--by its rousing (electrifying?) intro, its mesmerizingly complex note strings, its uplifting energy, and an unexplainably nostalgic quality that had a way of capturing the essence and the spirit of that particular moment in my gaming history; it said everything about the time and place in which I was currently living in. I considered it to be one of the series' best tunes. (And I still do! I listen to it quite frequently and especially when I desire to think about that era and remember why I loved it).

Dr. Wily's Revenge was a game whose value would increase for me anytime I decided to play it and do so with the intention of examining and observing it.

When, for instance, I took the time to stop and listen its title-screen theme, I learned something important. I discovered that what lied beyond the tune's intro was a surprisingly inspired, engaging composition. And years later, when I no longer had an attention-deficit and decided to finally listen to the tune in full, I discovered that it was more than just inspired in character; it was, to a greater degree, a powerfully expressive tune that was able to evoke many strong emotions and therein tell an invigorating tale of a hero's journey--of his determined march, necessary struggle, and gratifying triumph.

It was a masterful piece and one of the game's defining aspects.

Over time, most of my negative feelings faded, and I started to see Dr. Wily's Revenge in a new light. I started to like it. And soon I came to realize that it was a good game despite its flaws.

My only lasting disappointment was the way in which it handled the Mega Man 2 Robot Masters. I didn't like that they weren't supplied their own stages and were instead confined to the capsule rooms in the first Wily stage. It wasn't respectful representation, I thought. Bubble Man, Heat Man, Flash Man and Quick Man were, in my eyes, members of a legendary ensemble of Robot Masters, and thus they deserved better treatment; they deserved their own stage-select screen, stage environments, and boss music!

Still, I was happy that they were there. They were, to me, iconic Robot Masters, and I thrilled to get the chance to see them and fight them again. Also, I loved what they did for the game. Their appearing alongside Mega Man Robot Masters, who came from a world whose atmosphere was so tonally different from Mega Man 2's, provided the game a strong air of surreality. It made it feel as though two very different worlds were colliding.

The true fun, though, was in finding out if their new weaknesses were in any way consistent with their Mega Man 2 weaknesses. "Will the Ice Slasher work on Heat Man, since it was so effective on the similarly themed Fire Man?" I wondered. "And will the sharp, boomerang-like Cut Blade hurt Bubble Man as much as the similarly designed Quick Boomerang did?"

My only disappointment was that there was no way to find out if the Mega Man 2 Robot Master's weapons worked on the Mega Man Robot Masters. It would have been fun to see if the Atomic Fire worked on Cut Man or if the Bubble Lead worked on Fire Man!

It was unfortunate, though, that there wasn't much you could do with the Mega Man 2 Robot Master weapons. There were only a few obstacles built with their use in mind, and you got them so late in the game that there simply wasn't enough time to experiment with them and put them to use! The only useful weapon was the Atomic Fire, which, when fully charged, could destroy certain barriers, and it's fortunate that it possessed that capability; had it not, it would have been rendered completely redundant by Fire Man's Fire Storm (yet, still, there was a little too much overlap, and I couldn't help but feel as though it would have been better decision for Capcom to avoid such overlap by bringing over one of Mega Man 2's non-fire-type Robot Masters instead)!

And I didn't know what the hell was going on with Bubble Man, who was flickering and flashing so wildly that he could barely be said to exist!

That's the price of excessive ambition, I guess.

And I can't go without mentioning how much I liked the addition of Enker, the "Mega Man Killer." He was a cool-looking enemy, and I thought it was neat how he could absorb your Mega Buster pellets and then use them as fuel for his scroll attack (the more pellets he absorbed, the larger the blast would be!). The best part was that defeating him allowed you to obtain a wholly unique weapon, which was wild because up until that point, it had always been the rule that you could only obtain weapons from robots who had the word "Man" in their names. Being able to steal a weapon from a non-"Man"-named robot was such an interesting deviation from the norm; it felt like breaking a long-existing taboo in a wonderfully rebellious way!

The Enker fight was cool but always harrowing. At the time, my reflexes weren't particularly sharp, so I had trouble reading his movements, and usually I'd have to resort to guessing as to whether he would jump or dash across the room. And resultantly I'd only have a 50/50 shot of beating him.

I got better over time, though!

Though I enjoyed playing Dr. Wily's Revenge, I didn't return to it very often. It's incredibly high difficulty discouraged from doing so. I mean, this game was hard, man! On the difficulty scale, it was four or five rungs higher than the original Mega Man, which had previously been the benchmark for hard Mega Man games. And since my opinion (at the time) was that the original Mega Man was a considerably challenging game, that "rungs-higher" distinction really said something about Dr. Wily's Revenge. It spoke of an extreme level of difficulty!

Because the game was so difficult, I wasn't able to beat it. Hell--I couldn't even clear individual stages without struggle! It took me about a year to improve to a point in which I could capably clear Ice Man and Cut Man's respective stages, whose falling-icicle and circling-cutter obstacles were absolute terrors. Before then, they had always carved me into pieces!

And the Wily stages' difficulty was insane! Dr. Wily's Revenge's stages weren't like the console games', which had reasonable length and were pretty manageable, no. Its stages, in great contrast, were super-long and and intent on constantly bombarding you with perilous platforming challenges. They were pure endurance runs.

I could reach the second Wily stage, which was set within an outer-space fortress, but I wasn't skilled enough to clear it. I could only make it as far as the second disappearing-and-reappearing-blocks segment, which was overly long and incredibly difficult to traverse. For a long time, that segment was the bane of my existence. I dreaded it. Whenever I'd reach it, I'd immediately get the sinking feeling that my game was about to end. And it always would.

So I couldn't beat Dr. Wily's Revenge. And that bummed me out because I felt as though I was a Mega Man master. Beating Mega Man games was what I did! It was an essential part of being a series fan, I felt. But I just couldn't do it. And my failures weighed on me.

I returned to Dr. Wily's Revenge every few weeks or so with the intention of beating it, and each time the result would be the same: I'd repeatedly Game Over in the second Wily stage and eventually give up.

On rare occasions, I'd manage to put in a great performance and actually reach the stage's endpoint and engage with Wily's death machine. The problem, though, was that I could not, for the life of me, figure out what the second-phase machine's weakness was! I'd attack every part of it with every weapon in my inventory, including the Carry, and somehow never deplete a single bar of its health meter. And consequently all I could do was resign myself to the fate of being slowly dissected by the machine's darting claw.

That became the running theme of my play-throughs: I'd make it to Wily's machine and then fruitlessly spend the entire battle trying to figure out how to damage its second form. And after doing that several times, I'd give up in frustration.

At one point, I started to believe that the machine was simply indestructible.

"Is that why they named this game 'Dr. Wily's Revenge'?" I wondered. "Because he invariably beats you into submission with his undamageable machine?"

"Maybe it's the case," I thought, "that Capcom is using the portable space as testing ground for a new type of storytelling in games: end-boss battles that you're scripted to lose!"

Still, I never stopped trying to beat the game. My attempts weren't frequent, but whenever I did decide to play the game, I'd do so with a strong desire to take down that seemingly indomitable Wily machine.

It felt as though more than half a decade passed before I was finally able to achieve ultimate victory (in reality, it was only about two years; I know this because I recall beating the game not long after Mega Man IV released in 1993). I remember the moment well because it's intrinsically linked to the memorable environment in which it occurred. It was a summer afternoon, and I'd decided to play the game in our quiet, sunlit living room--a setting that always had the power to evoke feelings of anticipation and thus serve as the perfect place to enjoy quick, appetizing gaming sessions anytime I was looking forward to a big night out with family and friends (I don't remember what I was anticipating on that day, but it must've been something exciting!).

The run leading up to that moment was, like all of the others, heading toward failure. I couldn't figure out how to hurt the second-phase machine, and I was moments away from eating a death. That's when I shouted "Screw it!" and decided to switch to Enker's weapon--the seemingly useless "scroll weapon" (as I identified it), with which I'd experimented a single time before determining that it had no practical use--and do so with the intention of rubbing it up against Wily's machine and going out in style.

Seconds later, something shocking happened--something that was revelatory to me in the same way that discovering fire was revelatory to cavemen: Enker's "scroll weapon" reflected one of the turrets' projectiles back toward the machine, and when it made contact with the machine, it inflicted damage! It finally happened! I finally figured it out! And I couldn't believe it was that simple!

At that point, finishing off Wily was easy. It was a matter of simple procedure. And in the end, I'd achieved a satisfying victory that served as my style of revenge for the for all of the torment the game put me through over that years-long period. I proved to myself that I could beat such a game. And consequently I grew so confident in my ability that I was able to capably beat the game each time I returned to it (and I did so frequently).

Thus Dr. Wily's Revenge became a regular part of my gaming diet for the rest of time. And I couldn't help but appreciate the fact that my entire experience with the game was, poetically, a mirror of my story with the original Mega Man. That's what made my relationship with it feel so special.

Over the years, I became increasingly aware of how much Dr. Wily's Revenge resembled the original Mega Man in terms of tone and atmosphere. I noticed that its visuals and music produced the same type of emanations. It was a lot like the original Mega Man in that it was identical to its sequels visually but still somehow felt like a separate work--like a uniquely classic game that came from a much-earlier era and one that had very different sensibilities. It was to the Game Boy Mega Man series what Mega Man was the NES Mega Man series; it had an air of rawness and sincerity to it, and thus it, much like its console counterpart, had the ability to evoke memories of a time when games were wonderfully experimental and daring and didn't feel as though they were coming directly off of an assembly line.

That's what I appreciated most about Dr. Wily's Revenge: It gave me a second opportunity to have a similarly-formative-feeling "first Mega Man experience," which was something I desperately wanted but never thought I'd get.

And my feelings haven't changed. I still strongly appreciate what Dr. Wily's Revenge does. That's why I continue to return to it on a regular basis. I love what it does. It's a great game, and I consider it to be my favorite entry in the Game Boy Mega Man series.

I still have problems with the game, sure. I'm still not a huge fan of its cramped level design, punishing knockback animation, and excessively lengthy Wily stages. They still annoy me to some degree. Yet, really, I don't see them as major issues. They don't diminish the experience for me. They don't prevent me from deriving great enjoyment from the game (for certain, I enjoy its challenge much more so than I did when I was 13). I always have a fun time when I play it.

And I'm sure that I'll continue to have fun with it in the decades ahead. I'm sure that it'll forever remain one of my go-to Game Boy games.

And, well, I feel that the best way for me to close out this piece is to highlight one of my favorite aspects of Mega Man: Dr. Wily's Revenge: its staff roll, which contains a number of memorable elements. The one I love most is the musical theme. It's a touching, wistful piece that says more than a series of images of ever could. It's able to evoke very strong feelings and emotions. That's why I look forward to listening to it each time I play the game. I count on it to being me back to the early days and remind me of how things used to be.

Up until recently, I wasn't aware of the tune's full context because I'd never paid close attention to the game's closing scene (usually I'd be in reflective state and thus preoccupied). I can see now, though, what the scene is and what the music is saying about it. The scene speaks of a lonely, yearning Mega Man whose mood suddenly begins to brighten as he walks toward the space fortress' leftmost window and sees that his home is coming closer and closer into view. And if we can sense anything, it's that home is really the only place he ever wants to be.

That's what the tune conveys. That's the story that it tells. And what it says means a lot to me.

And I have to say: I understand how the little fella feels. I know what it's like to want to go back to a place where things make sense. I know what it's like to want to be home. It's the place I long to be, too.

Hopefully, like Mega Man, I'll get back there one day.

No comments:

Post a Comment