How Samus Aran defiantly morph-ball-bombed her way into and through the sealed-off passages of my brainy database.

Sometimes it takes us a while to smarten up and realize that the most valuable objects in our possession are those that have been right there, in front of us, the entire time.

This was what I came to recognize when finally I made a sincere effort to advance through and understand Metroid, which in our earliest months together had done nothing but consistently leave me feeling perplexed. Really, though, the game and I had been having trouble connecting ever since the day we were introduced.

It all started on that eventful Christmas Day in 1988, when my aunt and grandmother gave me The Legend of Zelda and Metroid, respectively, as gifts. Each triggered a very different reaction: As I looked over both sides of Metroid's silver box, with its unconventionally pixelated cover art and peculiar-looking preview screenshots, I wasn't sure what, exactly, to make of the game. "What is this?" I wondered, forgetting for a moment that I'd heard its title mentioned in the past. Outwardly, there were no such expressions; I was lost for words--nonplussed to such a degree that all I could do was stand there silently and stare at the box. My hope was that my empty gazing would be interpreted as keen examination (in such a scenario, you have to do what you can to avoid hurting the gift-giver's feelings).

Ultimately, the prevailing feeling was one of complete disinterest. I simply couldn't think of any reason as to why I should care about this "Metroid" game. Once everyone stopped paying attention, I tossed it aside, promptly dismissing it (which was par for the course with the younger version of me, who was quick to disregard any property that wasn't instantly familiar to him).

Conversely, I was excited to have in my hands a copy of The Legend of Zelda, which I'd seen in action and desired to play. In particular, I was taken with its box's wonderfully unique design details--its alluring golden hue and its most novel visual touch: a crest whose upper-left charge had been cut from the box to allow for a portion of the game's inlying, equally gold game pak to be displayed as one of its elements! "How interesting!" I thought. I'd never seen anything like it on a game box!

Oh, I was stoked about how this day was playing out. It started with my becoming a first-time console-owner--an event was surreal enough on its own--and now, just a few hours later, I already had myself a small collection of games! I couldn't wait to start tearing into them. December 26th, when finally I'd be able to start enjoying my new games without interruption, couldn't come soon enough!

Though, I wasn't sure that I'd be affording much time, if any, to Metroid, images of which would rarely surface whenever I was thinking about my new games and how I was going to plan my week around them.

And that's pretty much how it worked out: In the following days, I focused all of my attention on The Legend of Zelda and Super Mario Bros. I spent every available hour alternating between the two, joyously jumping back and forth between the captivating worlds of Hyrule and the Mushroom Kingdom. Metroid didn't figure into the equation; no--I completely ignored it, my lack of interest so severe that I couldn't even motivate myself to remove the plastic from its box. Based on how I was feeling, it didn't appear likely that Metroid was going to be getting any play during the Christmas break.

However, I did wind up giving Metroid a shot. Sometime during the week, on a whim, I decided that it might be worth it to at least sample the game--see what it was about. So I popped Metroid into the NES and proceeded to appraise it.

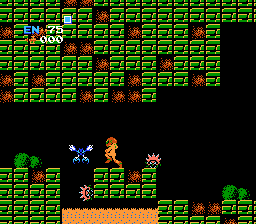

And, well, it was all rather bewildering: For twenty minutes or so, I confusedly ran and rolled about what appeared to be a series of discontinuous, haphazardly woven halls and corridors and somehow failed to make a lick of progress. The only thing I learned was that Metroid, unlike every other side-scrolling action game I'd ever played, had not a single immediately-obvious goal, which amounted to one of the most jarring breaks in convention I'd ever experienced.

The game's mode of level design just didn't make any sense to me. "Where's the way forward?!" I kept asking. "And why can't I find the first boss?!"

Never once did I know where I was or what I was supposed to be doing. "Should I be going left or right at this juncture?" I'd wonder in confusion anytime I arrived at one of the game's branching paths, which were becoming so worryingly abundant that I was starting to feel overwhelmed by the number of possibilities; this particular level-design element worked to generate a type of intimidation factor that was distinct in how it weighed on me. Not knowing where to go first or in what order I needed to proceed was stressful.

I spent the entire session retreading the same ground over and over again, all the while waiting for the game to supply me some form--any form--of direction. But it never did. So from what it was presenting me, I could only come to the conclusion that Metroid was an unsystematic, incomprehensible mess of towering vertical corridors--the most ridiculously lengthy sort I'd ever traversed in a video game--similar-looking rooms, and frustrating dead ends. Everything about it was inexplicable.

Finally I found something: In the southeast portion of the map, I procured what looked to be a "missile" item; though, I could find no application for it. Hell--I wasn't even sure that it was intended to have an observable effect (why I didn't think to hit the Select button, I'm not sure). And in following this line of thought, I came up with an idea--a theory as to what this item was and how it might offer insight as to Metroid's true nature. "Maybe Metroid is akin to Adventure (one of my Atari 2600 favorites)," I speculated. "It could be that this missile icon is the game's big prize--the equivalent to Adventure's trophy--and now all I have to do to win the game is carry it back to the starting point in the blue-colored area!" To make certain, I hurried back to the game's opening screen!

Aaaaaaaand nothing happened. There were no fireworks to be seen. There was no victory fanfare to be heard. And there was no princess waiting for me. No--there were no signs, at all, that I'd accomplished anything. Instead the game continued on uninterrupted, its defiant unyielding a clear sign that I was far off the mark.

I just didn't get it. This "Metroid" wasn't functioning like any side-scrolling game I'd ever played--like any of those linear action games I grew up playing in arcades or on the 2600 and the Commodore 64. I simply had no frame of reference for a game of its type. Even the indeterminately large, complexly structured Pitfall II: Lost Caverns, which I'd been playing since 1985, provided visual cues and had a way of funneling players in the right direction. But Metroid was obviously a different animal; it had no desire to adhere to established conventions. It was brazenly impenetrable. Sensing as much, I knew that it wasn't going to start making sense to me anytime soon. So I had no choice but to switch off the NES in puzzlement. "I'd be better off sticking with Mario and Zelda," I thought.

But I didn't completely toss Metroid aside. I returned to it sporadically over the next few months, hoping to gain a better understanding of its gameplay formula, though each experience would typically end the same way--with me not grasping its objectives and giving up after about ten minutes.

I wanted to find reasons to like Metroid--really I did--yet it kept trying to push me away.

Though, there was one aspect of the game with which I was enamored: the music. I was drawn to Metroid's tunes because they had such a strikingly distinct quality to them; each was a strangely entrancing combination of stimulating, emotive and evocative. Thinking about all of the games I'd played up to this point, I couldn't recall any whose compositions could boast of possessing such propensity.

First there was the title-screen theme, which was unlike any other I'd ever heard. Whenever I'd listen to it, I couldn't help but feel moved. Its progression had a way of slowly absorbing me; its opening series of pronounced, reverberant bass notes would soften me up--sufficiently alter my emotional state--and then the melancholic, wistful score that followed would promptly reel me in, its somber strains conspiring to leave me feeling a combination of sad and contemplative. Never before had video-game music managed to subjugate me in this manner--to trigger these types of emotions within me and render me captive to them. And never before had a title theme done so well to set the tone and define a game's character.

I was always sure to initiate any Metroid experience by letting this title theme play for one full loop. In any such period, I'd give myself over to it--allow it the authority to influence my thoughts and establish the tenor. (I paid less attention to the mission brief, which was so poorly communicated that it barely registered as important or relevant.)

I'd rely on the game's adrenalizing mission-starting jingle to act as the spark--get those goosebumps a-poppin'--and on the upbeat, invigorating Brinstar theme to fill me with spirit and serve as a continuous source of encouragement. The latter was among the best starting-area themes I'd ever heard; and like all others of its caliber, it had the power to make me feel heroic--whether I was listening to it as it emanated from the TV's speakers or playing it in my head. In the early days, when I was struggling to make progress, the Brinstar theme would keep me energized and engaged. Well, for as long as it could, at least--until I'd grow too frustrated to continue on.

In between sessions, hoping to attain some degree of knowledge, I'd read through the manual and look for hints as to how to meaningfully progress (had I done this on day one, I might've come into the game with at least a rudimentary understanding of its systems). Another motivating factor was that I liked reading through the manual; I derived a lot of enjoyment from poring over its content. It was, much like Zelda's manual, attractively packaged, well-designed, and rich with interesting information and imagery; it featured (a) detailed explanations of the game's backstory, environments, weapons and enemies and (b) accompanying visuals that were impressively rendered and imagination-stirring. I always had fun reading through and thinking about the game's story--about the space pirates' misdeeds and Galactic Federation's efforts to counter them; the emergence of the "space hunters"; and how the Metroids became the universe's greatest threat.

More so, I loved to peruse the enemy list--to analyze the visually appealing depictions and memorize the names of Zebes' indigenous creatures (mainly because I had a deep interest in reading about and drawing monsters), a lot of which I never thought I'd get to see! (I have to say, though, that Ridley's depiction gave me an entirely false impression of the character, which I saw as a weird-lookin' alien; his wasn't a dragon's maw, it appeared, but instead a long, segmented snout. I realized, later on, that the localizing artist had based his rendering on the character sprite, which he obviously misinterpreted.)

I came to see the manual--or, rather, the reading of the manual--as an essential aspect of the Metroid experience. Its words and images provided some very important context and helped me to form a strong mental image of Metroid's world. That it could supply this extra layer of texture was a big reason why I was so drawn to it. I read through it dozens of times over the years (and in doing so wore it out to the point that it was barely able to maintain its binding).

My fondness for Metroid's manual (and Zelda's, for that matter) and the way in which it contributed the characters' and settings' development was what convinced me that I should always read a game's manual before playing it. Thus a tradition was born.

Metroid had other appealing aspects. For one, it featured first-rate movement and shooting mechanics; there was a lot of fun to be had in slickly twisting Samus through the air and rapidly blasting enemies. In observing how they functioned, I came to the conclusion that the controls and physics were an expansion of Super Mario Bros.'s. The way I saw it, Metroid was building upon Mario's template by putting further emphasis on fluid motion and directional influence and adding a second type of jump (a cool-looking spinning jump that you could execute by tapping the button while in motion) and the ability to fire upward. That's what made it feel evolutionary.

The Morph Ball (or the "Maru Mari," as the manual termed it) was a splendid addition, I thought. It made for the most interesting, inventive mechanic I'd seen in a long time: an ability using which you could shift into ball form--in effect reducing your size to half--for the purpose of rolling through otherwise-inaccessible narrow tunnels and passages; its inclusion promised to add a new dimension to the gameplay. I had fun experimenting with it; in particular, I found great enjoyment in bouncing my way down Brinstar's long vertical corridors and therein attempting to dodge all of the pesky Rippers and platform-circling Geemers.

Also, the game was filled with disturbing-looking creatures, which for me was a big plus. I liked to observe how they operated and discern which enemy classes they belonged to; whenever I'd travel to a new area, I'd take note of how its fiery, horned and crazy-legged critters were maneuvering about and try to determine how they differed from the earlier creatures of which they were obviously reskins.

I remember how I first perceived these enemies: The larger arcing-types (Rios, Gerutas, Holtzes, Side Hoppers, etc.) were scary because they inflicted heavy damage and were absolute bullet-sponges--more so than any minor enemies I'd ever encountered in games; I was the overly conservative sort--always hesitant to expend weapon stock because I was that sure I'd need it to deal with a tougher enemy that was waiting down the line--so I was always engaged them with beams. In fact, for the first several years, I'd use missiles only in very specific instances: when I was blasting open red doors or fighting Kraid, Metroids or Mother Brain.

Also, I was sure that those pipe-inhabiting enemies were saying "Whaaaaaaaat? as they emerged, theirs an expression of shock that someone was dumb enough to traverse these spaces.

I was a strange boy.

But the reality was that I was engaged in an act of elaborate procrastination. I knew that inevitably I was going to move on from Metroid--that all I was doing here was desperately attempting to wring some form of enjoyment out of the game so that I could convince myself that I gave it a fair chance. It was a thoughtful gift, after all, and I didn't want to feel guilty about abandoning it.

Metroid controlled well and boasted some intriguing elements, yeah, but the fact remained that I had no firm grasp on what it was or what it wanted me to do. It just wasn't my kind of game.

So I had to leave it behind.

Fast-forward to eight months later, on a boring summer day in early August--weeks before my birthday and during a period in which I'd played all of my NES favorites to the point of fatigue. I was looking for something new to play, though no game in my collection could meet such a qualification; all available items were months-old. Also, I didn't have enough money to buy a new game (and I wouldn't until August 18th). Desperate to fill the void in any way that I could, I decided that I might as well load up Metroid, of which I'd seen so little that it might as well have been considered "new," and make a determined effort to finally solve its mystery.

So I obtained every weapon and item of which I was currently aware--the long beam, bombs, some missiles expansions, and a few energy tanks--and headed down to Norfair ("Purple Brinstar," as I had mistakenly dubbed it), which was as far as I'd ever traversed. I wasn't overly familiar with Norfair's map structure because in previous sessions I refused to hang around this area for any length of time, since its troubling combination of similar-looking rooms and hard-hitting enemies made me feel uneasy. If ever I was lingering around these parts, then it was only because I wanted to listen to Norfair's understated, mysterious-sounding musical theme, whose slower tempo and curiously uncomplicated composition (only two instruments) rendered a tune that was quietly unnerving yet oddly alluring.

I termed this piece "The Gangster Theme" because it had a chill vibe and what I interpreted to be an "old-style rhythm," like something you'd hear in a film noir production. It was a suitable theme for Norfair, I thought, because this was obviously where the space pirates, an organized-crime syndicate, "hung out." There were no signs of them, of course, but my imagination told me that they were definitely there somewhere, hiding in spaces on which I'd likely never lay eyes.

More relevantly, this tune imbued Norfair with an investigative atmosphere that spoke of concealed treasures. The more I listened to it, the more I was convinced that whatever I was missing had to be here--that an item of great importance was probably resting someplace within these halls.

But I just wasn't able to find anything. There were no transitional elevators or passages, and all of the available paths kept looping back to the same one or two locations. There was literally nowhere to go. "Where's the rest of the game?" I wondered in frustration.

After meticulously, exhaustively exploring every inch of Norfair, for what seemed like hours, and utterly failing to discover a means of progression, I ran out of patience. At that moment, I was ready to give up and swear off Metroid for good. But then something happened. Suddenly there was an unanticipated, revelatory breakthrough.

*ba-doop-ba-doop-ba-doop - BOOM*

While randomly spamming bombs in Norfair's eastmost vertical corridor, I blew open a hole in its floor! The second-to-last block from the right had disappeared from view, its absence revealing a hidden passage (it's recently been pointed out that the camera here is positioned half a screen lower, which is likely a hint that something rests below this floor)! That was it! That, right there, was the game's big secret: You could bomb through walls and floors!

"How was I supposed to know that?!" I wondered, flabbergasted by this discovery. I mean, sure--the manual mentioned that you could use bombs to "break down barriers," but I assumed that it was talking about blue doors and those obviously-destructible orange blocks. I never would have guessed that ordinary floor tiles were included in that category!

"Now I get it!"

As I dropped down that newly uncovered fissure, it all began to make sense. "This is what Metroid is about!" I said to myself.

And now that I was working with the knowledge that the path forward could be hiding behind any inconspicuous-looking block, I was certain that the game was about to completely open itself up to me.

Suddenly there was a zest to my exploratory efforts. I was excited to find out what lay ahead--to discover what was waiting for me beyond each newly appearing door and surface. As I tunneled deeper and deeper into Norfair, my curiosity-level continued to rise. As the terrain grew weirder and scarier, I became more immersed in the action. Feelings of anxiousness and trepidation remained, certainly, but now they were counterbalanced by the motivating forces of drive and determination. And all of this was happening because Metroid was able to play with my emotions in a way that no game ever had before. It could make me feel apprehensive, intimidated, tense, eager and adventurous all at the same time; its every environment--its every color-scheme and texture--had the power to evoke an anomalous mixture of wonder and concern. "Are those Metroid eggs?!" I worried the first time I entered one of those bubble-filled rooms. "And are they going to suddenly hatch?!"

This was my state of mind as I traveled down to Lower Norfair, where I was met by a sinister-sounding musical theme whose ominous-sounding, maddeningly harsh strains filled me with fear and made me feel nervous about the idea of rushing in. Yet I could find a way to feed off of its oppressive resonance and let it push me to focus in and remain resolute.

At that point, it was safe to say that Metroid had fully captured me. I didn't care how many hours were left or if the game's complexity-level was set to increase exponentially--I was going to play it all the way through to the end. There would be no further hindrances in my now-exuberant exploration of its world.

Before the day was over, I managed to brave the fiery depths of Lower Norfair, conquer Ridley, and complete the long, arduous trek back up to Brinstar, whose energetic, heroic theme now seemed more welcoming and reassuring than it did previously (I'd even say "rewarding").

The next day was all about putting my newfound surface-blasting ability to work in Brinstar and the opening sections of Norfair, which I was certain were hiding more secrets. I had a little help: Thanks to some tips from my friend Dominick, I was able to discover the locations of the Varia Suit and that ceiling-embedded energy tank near the low-hanging obstruction. Though, I managed to locate and procure the High Jump Boots and Screw Attack on my own (but that's as far as I explored in Norfair's green-hued section; after surveying its opening rooms and learning of its confusingly labyrinthine nature, I got spooked and retreated back to the Norfair's known portion; it wasn't until several months later that I found the nerve to explore around the green section).

Before long, I was making my first visit to Kraid's hideout, wherein there was a continuing of the theme of a newly traversed area's music immediately grabbing hold of me. But there was something notably different about this tune's tone and tenor; this one was an emotionally drenched piece the likes of which I'd never heard in a video game. For the first time in my life, I felt it appropriate to set down the controller and listen for a few minutes; in that span, I attempted to (a) determine what it was the music was trying to tell me and (b) find the words to describe how it was affecting me. Had at the time I possessed adequate verbal skills, I would have said that it was "a painfully evocative piece whose disconsolate, somber strains express the nature of Samus' existence in a way that words simply can't." That was its power.

Metroid's music was playing a vital role in shaping my perception of its world. Every tune had a suggestive emotive quality that functioned to inform me of its associated environment's current state; each was designed to direct my emotions and therein influence the formation of my thoughts and visualizations. This was true of even the brief item-obtention fanfare--a strikingly wistful ditty that always impelled me to ruminate, if only for five seconds, on Metroid's nature. I'd never forget these tunes and how they made me feel.

After taking down the tough-skinned Kraid in an undisciplined, strategy-bereft slugfest, I returned to Brinstar, raised the miniboss statues, and rolled my way across the materialized bridge to reach the last of the area's elevator rooms. Its lift dropped me off in Tourian (which at the time I called "Tourain," as if it were a misspelling of terrain), which exhibited a coldly gray, disturbingly intricate "mechanical" aesthetic. More jarring was its musical theme--the game's most unsettling piece; it was both alarming and menacing, its siren-like bassline and disturbingly synthetic-sounding "bubbling" sequences suggesting to me that great danger lay ahead.

Mine was some shaky progression, I recall. My traversal of Tourian was marked by jumpy encounters with Metroids and futile attempts to evade the infuriating Rinkas (the "annoying SpaghettiOs," as we often referred to them), which would continuously spawn right on top of me. The weird thing about Metroids was that they were rather easy to defeat and didn't drain health as quickly as I had imagined they would, yet they were nonetheless terrifying. It wasn't so much the knowledge that they could inflict considerable damage that had me on edge but rather the idea that they were potentially hiding around any corner, ready to charge at me at a moment's notice. In that regard, they functioned more as a psychological terror (a role to which they'd find themselves increasingly relegated in future games).

Soon I entered into Mother Brain's chamber, wherein the music grew only more threatening. My heart began to race, and consequently I struggled to focus. While frantically, sloppily assaulting the Zeebetites, I ran out of missiles and bit the dust. The next few attempts went just as poorly, though I was at least able to use these opportunities to get a read on the battle; and this learning process helped me to settle down a bit (also, being forced to tediously farm missiles back at Brinstar had the effect of reducing my anxiety-level--mostly because having to do so instead made me feel agitated). But eventually it all came together; in one particular attempt, I was able to reach the chamber's end portion with an adequate amount of health and thereafter crack through the Mother Brain's protective glass casing, pump her full of missiles, and blow her to smithereens, therein putting an end to the wicked mastermind's evil machinations.

For me, this was quite an accomplishment. In my six years of gaming, I'd never faced an end boss that was as tough as Mother Brain.

The subsequent timed-escape sequence, which had me ascending up a mile-long corridor via a series of remarkably narrow platforms, was much easier in comparison, though I had some trouble with it because I was again nervous and trembly and couldn't land the required tight jumps with any consistency; the beeping noises and the visual of a rapidly draining timer only heightened the pressure. Though, I managed to climb to the top and escape via the elevator. That's when I learned Metroid's big secret--that Samus was a woman and, as far as I knew, the first heroine to play a leading role in an action game (I got the third-best ending, wherein only her helmet was removed, but this was lost on me because I wasn't yet aware that the game had multiple endings; I just assumed that there was only one). At the time, though, I thought of this revelation as nothing more than a cheap swerve, done mainly to "shock" audiences. "How dumb," I thought. But to its credit, Nintendo showed itself to be serious about the decision--to believe in the character--and in the ensuing years made a sincere effort to turn Samus into a legitimate gaming icon.

Though, the most significant happening was that Metroid had completely won me over. I couldn't explain what, exactly, "Metroid" was or adequately articulate why it was different from the other action-adventure games I'd played, no, but I could say with certainty that I was a fan of everything it did--of every idea it presented. It had succeeded wildly in opening my eyes to new possibilities. It had proven the viability of exploration-based side-scrollers. And it had shown that it was, indeed, my kind of game.

I couldn't get enough of Metroid. In the following weeks, I played through it multiple times, both for fun and for the purpose of earning one of the better endings, about which Dominick informed me. Mind you, it wasn't that I was a perv who wanted to see Samus stripped down to her skivvies but rather that I wanted to unlock and experience what had been described to me as a somewhat-altered "Second Quest" wherein you play as a suitless Samus. Normally I had an aversion to speeding through games for the purpose of satisfying time-based conditions, since (a) time limits stressed me out and (b) generally I preferred to play games at a more leisurely pace, but this time I could find justification for doing so; I was of course thinking of Zelda, which had shown me that post-game content may very well be worth the effort to unlock. And in Metroid's case, it was; playing through a second mission as the aesthetically unique suitless Samus, who in addition started with all of the previously collected power-ups (sans energy tanks), was always a treat.

The more I played Metroid, the more I fell in love with it. The more I analyzed and thought about the design philosophy that fueled its gameplay, the more I felt inspired to advocate for it. Whether I was engaging in a normal run or one undertaken with a suitless Samus, I was always excited to be running about about Zebes' labyrinthine spaces, wherein I could have a great time searching for hidden missile packs and energy tanks and discovering new terrain, like that seemingly innocuous room that turned out to be the home of the inexplicable fake Kraid ("Why is this character even in the game?" I wondered "And why is he placed here, atop an orange pipe in some random corridor?!").

Well, to be honest, I didn't happen upon the Fake Kraid or explore some of the nonessential areas until months or even years later, when I started to grow less fearful of games that were labyrinthine in nature. In Metroid's case, I'd convinced myself, using a very unscientific sampling method, that it was an unfathomably large game and that attempting to explore it thoroughly would only result in my getting hopelessly lost and confused--inevitably overwhelmed to the point of mental exhaustion; that's why I thought it best never to wander too far off the main path (or whatever constituted the most convenient path). Further exposure to the genre--specifically to Metroid-style games like Rygar, Rambo and such--was what helped to gradually acclimate me to highly labyrinthine games--alter my disposition to where I would embrace becoming lost and regard the act of such as an element essential to the action-adventure experience. And when I went back and played Metroid with that mindset, I came to have an even greater appreciation for it.

In the earlier days, I focused more on experimentation and trying to access certain spaces out of sequence. This became my obsession after my friend Dominick taught me how to obtain the Varia Suit without the High Jump ability (by executing a very precise series of actions, you can manipulate the Waver into flying up to the adjacent room, wherein you can freeze it and use it as a platform) and enter Tourian early (by luring a Rio into the statue room, freezing it when it flies near the narrow aperture on the left side, and then bomb jumping off of it). I wasn't able to discover any additional sequence-breaks, unfortunately, but I never stopped believing that there were more of them. That belief, alone, fueled a large amount of play-throughs.

I'd break out Metroid any chance that I could. If it was a Saturday afternoon and I had an hour to kill before heading out to meet with family on Vanderbilt Street, I'd challenge myself to finish the game within that span. If a friend had grown fatigued following a long session wherein we marathoned all of our co-op favorites (Balloon Fight, Ice Climber, Mega Man 2, etc.), I'd happily honor his request that I pop in Metroid and demonstrate my run-and-gun skills while he relax with a soda or some chips and offer some commentary. Other times we'd stealthily exit the pool and sneak back into the house--up to my room--and get in a quick game before the big barbecue. The one- or two-hour wait leading up to a Thanksgiving or Christmas dinner? Always a prime opportunity. Had time to spare after finishing up my homework? I was makin' a b-line for planet Zebes.

I could always find motivation to return to Metroid, whether it was discovering sequence-breaks, completing the game as quickly as possible, or attempting a limited-item run. Hell--I was so eager to squeeze additional value out of the game that I'd act upon any neighborhood lore or oft-repeated urban legend, no matter how fantastical-sounding it was. I remember how I spent entire days fruitlessly searching for the rumored "secret world," which according to Dominick's brother, Joey, was a hidden area that housed 100 Ridleys, 100 Kraids and 100 Mother Brains. Though, he was mum when it came to explaining the important details, like where this secret area was located, how it could be accessed, or what the reward was for clearing it out (I wondered, also, how the NES was going to process all of this data--render 300-plus sprites--without exploding).

Sadly, no one was able to locate it.

Eventually people did discover a "secret world"--just not the one that was spoken about in legend. Information about how to access it was relayed by Nintendo Power, whose Classified Information section illustrated the process: In Lower Norfair's gray energy-tank room, you could clip into the ceiling by letting the left door close on top of Samus and in following rapidly alternate between up and down on the d-pad to scroll her upward, pixel by pixel, until the screen had shifted up far enough for her enter the third blue door in a newly revealed vertical corridor. I wasted no time in testing it.

What I found beyond the door was quite fascinating, sure, though it was nothing that could match the legend. No--inside was only a series of bizarrely constructed rooms (those with fall-through floors and doors that led nowhere), each rendered using assets as randomly drawn from the game's map data. Basically, it was the game's way of using some quick improvisation to fill in the map's out-of-bounds spaces, which were supposed to be empty. In truth, there were many more of these "secret worlds"; in the days that followed, I spent countless hours wedging myself into doors and scrolling up past every ceiling structure I came across. Though, I never did discover anything truly special--just more in the way of freaky, malformed variants of already-existing rooms.

But I didn't stop looking! I was still convinced that a true "secret world" had to be hidden in there somewhere. And I was desperate to find it. That's why I was all-too-willing to abandon skepticism when my friend Mike, a known storyteller, informed me of "the secret meeting room," which he claimed lay beyond the left wall near the game's starting point in Brinstar. It was there, he said, where you could find the long table at which the Federation met before they elected to contact Samus Aran (you remember--the scene as depicted on the manual's third page, which you can see near the start of this piece). I believed him because Super Metroid had recently seen release and its version of that wall was indeed guarding a secret. I could argue that this was a signal and furthermore make the extrapolation that Metroid's wall, too, had to be destructible!

Me being the dope that I was, I proceeded to spend waaaaaay too many hours trying to bomb and glitch through that wall. I even tried to scroll my way up to the targeted space from Kraid's hideout using the secret-world method in the long vertical corridor that ran parallel to it (according to the Nintendo Power map). And I would have kept at it had I not suddenly remembered a key detail: "Wait a minute." I said to myself. "The Federation didn't meet on Zebes. No--that's the place they were trying to infiltrate!"

How stupid.

Unfortunately, Mike moved to Staten Island weeks before I had this realization, so I was never able to confront him on the matter.

But that was the magic of Metroid. It could stir the imagination like no other--make you believe that planet Zebes was a 1,000-times larger than it actually was. It could convince you that there were vast secret worlds hiding behind every wall and surface. It could fill you with the sense that Zebes was a living, breathing entity capable of expanding on its own. To me, Metroid's world was formed via the combination of two equal parts: what was real and what I imagined there to be. That would forever remain my conception of Zebes.

It's never mattered to me that Metroid is rife with glitches and programming flaws. No--I see them as decidedly enriching. Really, the game wouldn't be what it is were enemies not able to follow you through doors and enter into rooms in which they were never meant to appear, or if it wasn't possible to clip your way up to a "secret world." The game would be lacking for flavor, I say, if it were bereft for instances wherein falling down long vertical corridors produces series of discolored blocks because data can't be retrieved that quickly. And I don't even care that so many of the rooms look the same (the recurrence of recycled environments an obvious memory-limitation workaround); their capacity to provoke such strong feelings of uncertainty--of being lost and afraid--works out to be a key ingredient in the development of the game's all-important psychological element.

As I've said previously: Back then, a game's glitches and exploits were considered to be essential parts of the experience. Though unintended, they would forever be remembered as intrinsic elements that provided us some additional entertainment value.

This is certainly true of Metroid's. I wouldn't remove a single one of them.

When people are asked to choose a descriptor that they think best defines the "Metroid experience"--makes them feel at one with the game--they tend to use words like atmospheric and isolation. Though, I feel that such terms fail to tell the whole story--that the people in question are merely identifying individual aspects of a much more powerful influence. Truthfully, I've never been able to adequately describe it. If I were to attempt to give it a name, it would be something along the lines of "cognitive immersion." That is, Metroid wants you to form a deeply personal, psychological connection with its world. It wants for you to absorb its aural, visual and environmental emanations and arrange them on your mind's canvas so that you can interpret them and form your own picture. As you traverse its environments, it wants you to think about what's happening in the periphery--in the places you won't ever see--as well as what's happening right in front of you. And it wants you to use this information to determine your place in its world--determine whether you feel invigorated, heroic, lost, sad or lonely.

Your constructing and developing of these mental visualizations help you to form an intimate connection to Metroid. That's exactly how it was with me: I was never more immersed in the action than when I was conceptualizing the game's story and thinking about Samus' plight. In my head, I put together an image of the stoic Samus and the planet's incognizant indigenous creatures, who live out uneventful lives wherein they trek across and endlessly circle around decaying structures while completely oblivious to what's happening around them, roaming about an unlivable, desolate planet located millions of miles away from civilization, all parties participating in a grand production about which no one will ever hear, learn or care. I viewed Samus' mission as one about surviving in the depths of an uncharted, faraway world and persisting in an effort to save unaware, ungrateful populaces from impending doom before moving on to her next in a series of unchronicled, unappreciated exploits.

These are the images that your mind renders when you're in the thick of it. Theirs represent the influence you're under whenever you travel a route that looks familiar but drops you into unknown territory--so deep that you're not sure how to get back to the previous intersection. Whenever you're despondently stumbling about a confusingly labyrinthine set of corridors and surrounded by aggressive, hard-hitting Gerutas, Holtzes and Dessgeegas. Whenever you have to resort to slowly, guardedly inching your way through a long claustrophobic passage because it's infested with large numbers of rebounding Multiviolas and because you're bereft of the Screw Attack ability and your health is dangerously low, your sense of trepidation exacerbated by the irritating beeping noises. And whenever you're lost, struggling to survive, and wondering, "How the hell am I going to get out of this place?"

And when the images in your mind overlap with the images you're seeing on the screen, that's when the connection will be made. That's when you'll know that you're having a "Metroid experience."

Metroid is the game that introduced me to and ultimately solidified my love for the exploration-based action-adventure genre (which due in part to Metroid's profound influence has since been characteristically labeled the "Metroidvania" genre by fans). Had I made the decision to toss it aside and never give it another look, I probably wouldn't have become such a huge fan of Metroid-style games. It's likely that I would have passed up on some of the greatest, most impactful games I've ever played--a list that includes its fantastic sequels and absolute classics like Blaster Master, Rygar (one of my all-time favorites) and the future Castlevania: Symphony of the Night.

Thank goodness I stuck with it. Gunpei Yokoi, Yoshio Sakamoto, Hip Tananka and the rest of the people at R&D1 and Intelligent Systems created something truly special, and I'm so glad that I came to recognize as much. I don't know who I would be had I not.

Even today Metroid remains in my regular rotation. It usually works out that I return to it several times a year. And when I play it, I seek to get the most out of the experience; I make sure to engage in a 100% run wherein I explore every inch of planet Zebes and spend each moment soaking up its every vibe. And I do so with while under the influence of those same psychologically stimulating feelings of apprehension and anxiety that so gripped me when I was 12. It still has that magic. To me it always will.

So concluded what was Metroid's slow, unexpected ascent into my pantheon of video-game favorites. It came from out of nowhere with the mission to shake up my world and lead me to new horizons, and in that it succeeded. If Super Mario Bros. and The Legend of Zelda represented my enthusiastic first steps into a whimsical world of fantasy and earthly pleasures, then Metroid was my eye-opening rocket ride into the deep, dark expanses of infinite space.

Sometimes, there's no place I'd rather be.

I grew up in the early 90s, and "Super Metroid" was my first exposure to the series. I played through it using Nintendo's official guide - which had amazing illustrations and the all-important bestiary - and finally beat it one night with my family present. Since I'm sure you know how thrilling the final areas of that game are, you can imagine what that experience was like for me. Super Metroid is still probably my No. 1 game.

ReplyDeleteSince I didn't play Metroid for NES until after I experienced Super Metroid, the older game needed to work a bit before I enjoyed it as much. I've not beaten it nearly as many times as SM, but it's definitely in my top 10 for my NES library.

As a side note, I recently got a Famicom Disk System along with Metroid, and it's pretty awesome to play it with the enhanced sounds and an actual save feature. The password system for the NES Metroid is just atrocious!