Why the enduring block-dropping puzzle game continues to drive me mad.

By 1990, the NES, thanks to its succession of life-altering heavy hitters, had become my main platform for video games. It had fully captured me, and insofar it had completely redefined for me what "video games" were.

As a consequence, though, I started to fall into a diseased state of thinking. Because my world had been so indelibly shaped by expansive, large-scale games like Contra, The Legend of Zelda, Metroid, Mega Man 2 and Rygar, I started to believe that only games of their caliber had the power to truly influence and inspire me and capture my imagination. They were, I thought, the only games that were worth my time.

I mean, I still loved simple arcade-like games like Trojan, Renegade and Wrecking Crew and all of my Atari 2600 and Commodore 64 favorites, yeah, but I'd come to think that such games were second-tier and that they simply weren't capable of having that same level of emotional impact. They could never inspire me in the same way, I was convinced.

I remained stuck in that mindset for a long time.

And it wasn't that I just snapped out of it one day, no. I didn't. Rather, I was slowly eased out of that mindset over a number of years. At different times, highly impactful smaller-scale games came along and challenged my conceptions. They forced me to question my beliefs and reexamine how I thought about video games. And in the end, they helped to undo my brainwashing.

A lot of games contributed to my reawakening. Many seeds were planted along the way. And the game that planted the largest number of them was Tetris, the humble little block-dropping puzzler.

I couldn't get excited for it, though, because I couldn't figure out what it was. I'd seen its action depicted multiple times, yeah, but in each instance, I was unable to grasp its concept. I couldn't understand what its point was or why it was supposed to be interesting. And after a while, I decided that keeping up with the game was pointless.

It was best, I thought, to pass on Nintendo's new "block game" and focus my attention elsewhere. So that's what I did.

Before long, Tetris faded from my consciousness, and I basically forgot that it existed. And that's how it remained until the middle portion of 1990, when Tetris started appearing in all of my friends and cousins' home. That's when I discovered what Tetris actually was. It was, I learned, a puzzle game.

I was a huge puzzle-game fan, so that fact, alone, was enough to rouse my interest. Though, what really intrigued me was that Tetris wasn't your standard puzzle game, no; it was something genuinely new--something entirely novel. And when I played it, I was instantly hooked. Its action was fun and engaging in a wonderfully unique way; I'd never experienced anything like it.

I wasn't sure that it was entirely correct to call Tetris as "puzzle game," since it wasn't asking the player to solve any puzzles (at the time, I associated the "puzzle game" label mainly with games in which you worked your way through mazes, busted blocks, and fit shapes into corresponding spaces), but I knew that it was a great game regardless of its classification.

And, well, you know what that meant!

I went out and bought myself a copy of Tetris sometime around the start of the summer of 1990, when school was out and I was free to spend all of my time learning about the game's intricacies and developing my own strategies.

In my earliest sessions, I tended to employ a minimalist strategy and treat the experience as an endurance test. I'd focus on clearing away single lines and trying to make it to the highest level possible. At the time, I could usually make it to around Level 12 or 13. That's when the game speed would become too much for me and things would quickly fall apart; at that point, a single screw-up would predictably result in the creation of a tall junk pillar that I'd be incapable of clearing away. And then it'd be over.

With a lot of practice, I became a more skilled Tetris player, and I began centering my game around putting together strings of Tetrises. Though, I still struggled with the double-digit levels' speed increase, so I'd tend to revert back to my minimalistic strategy whenever I reached those levels (usually I'd start to revert when I reached Level 13).

The problem with the higher-speed levels, of course, was that they made setting up for Tetrises a very risky tactic. In these levels, the pieces were falling way too quickly, and there was never any guarantee that a line (or a "straight polyomino," as the line piece is officially called) would ever again appear. Things would get sticky whenever I was in a position in which I was set up for two or three Tetrises and it became obvious that a line wasn't going to be appearing anytime soon. At that point, the blocks would be piled so high that I'd quickly have to switch gears and employ a desperation survival strategy; I'd have to plug up the open column and try to create a flat surface and do so before it was too late.

And naturally, a line would appear right after I plugged up the open column. Because that's what Tetris did. It liked to mess with you. It liked to give you every piece but the one you desperately needed. It knew exactly what you wanted, and it was intent on withholding it from you for as long as possible.

After a while, I started to think that the game was purposely designed that way. "This has to be intentional," I'd angrily mumble to myself whenever I was in a position in which I needed a line and I'd gone more than 50 pieces without seeing one.

And then there were the other annoying things that Tetris was apt to do. Too often, it would start me off with a long string of Z-shaped Tetronimos and thus immediately put me in a big hole, and consequently I'd have to spend the first few minutes (and three or four levels) filling in the gaps and trying to gain control of the board.

And other times, it would insist on throwing out 10-15 square Tetronimos in a row and doing so in moments when the blocks were stacked high and the board's surface currently had nothing but one-block-wide gaps.

In instances such as those, I'd always think, "This game is actively trying to break me."

My mental image of Tetris' piece-choosing algorithm was that of a cackling old man hiding behind a curtain and mischievously manipulating a lever-filled control panel. I imagined that while he was bombarding me with one unwanted piece after the next, he was laughing maniacally and reveling in my suffering.

But even when Tetris was going out of its way to annoy me, it was still super fun to play. And I played it very often; I'd return it on the daily and sometimes multiple times per day. I'd sneak in sessions whenever I could--when I had a half hour to kill before my favorite cartoons came on, when I was waiting for my mom to finish cooking dinner, or when I was waiting for one of my friends to arrive. It just kept calling to me. And I could never resist.

Tetris was the single most addicting video game I'd ever played. In fact, it was the game that introduced me (and many other kids) to the word addicting. I'd never heard of it until then. But now I was aware of it, and I knew, from my Tetris experiences, exactly what it meant. Tetris personified it. Its name was basically synonymous with the word addiction.

None of us could stop playing it!

Its B-Type mode was fun, too, but overall it wasn't as compelling as A-Type. It was only exciting when you played it on Level 9, Height 5. None of the other level-height combinations had any challenge to them because, really, the pieces didn't fall fast enough to make you sweat.

So all I did was play on Level 9, Height 5--the only one that truly challenged me. I played it not only because it was challenging but also because I liked the reward that it offered: a lively victory screen on which all of my favorite Nintendo characters appeared. Each had an instrument in hand and could be seen synchronizing his or her movements to the victory music: the Bizet - Carmen Overture (all except for the Mario Bros., who were apparently bereft of musical talent and could only contribute by leaping in alternation). I was obsessed with this victory screen because of how it brought together characters from such wildly different worlds. Characters like Donkey Kong and Samus were as disparate as you could be (one was a cartoon character, and the other was a semi-realistic sci-fi adventurer), and seeing them and the rest of the markedly unique character types standing together was always surreal to me.

I have to admit, though, that initially I didn't realize that the character on the lower-left platform was Bowser. It didn't look much like him. Rather, it looked like some random green spiky monster. I figured that it was a dragonesque protagonist from some obscure Nintendo game (like maybe one of the light gun games I never got around to playing).

This victory screen was also a source of frustration for me because it included Pit (or "Kid Icarus," as I used to refer to him), the image of whom served to remind me that Nintendo was failing to properly utilize him. He was a beloved character from a classic NES game, I thought, and he deserved more (though, admittedly, I was more a fan of the character than I was of the game). Yet there we were, three years later, still waiting for a Kid Icarus sequel. So the only thing his appearance worked to do was highlight the fact that the character had been inexplicably absent for a long period of time. And it felt to me as though an important part of the Nintendo family was being slighted for some dumb reason.

I didn't overlook the fact that Tetris had some pretty great music, too. Its default theme (the creatively titled "Music - 1") was instantly iconic and, I thought, the perfect accompaniment to Tetris' distinct type of puzzle action. It was mysterious- and quizzical-sounding, and its slower tempo and higher pitch worked to create an understated feeling of anxiety. It presented itself as calm and soothing, though its real purpose was to lull you into a false sense of comfort and quietly vex you. And thus it perfectly defined Tetris' action.

Over time, though, I started to lean more toward Musics - 2 and 3. Music - 2 (which I identified as "the cowboy theme") had a lot more energy to it, and it kept me more engaged. And the cosmic-sounding Music - 3 was more seductively calming, and thus it was the best accompaniment in those many instances in which I was looking to relax and contemplate while playing Tetris.

Our interest in Tetris waned a bit over time, naturally, but still we continued to play it quite regularly. For the longest time, it remained the perfect go-to game in instances when we had some time to kill or when we'd finished playing three or four action games and row and now desired to mix things up and throw in some much-needed variety.

And the game gained some extra life when Nintendo Power revealed that it had a secret "Warp" code that you could input on the level-select screen: If you highlighted a level and then pressed Start while holding down the A button, you'd start ten levels ahead of the highlighted level! So now we were able to skip over the boring slow-moving levels and jump right to the tens and the teens, wherein the starting action was more intense.

Whenever I was feeling really brave, I'd try my luck at the ultra-fast Level 19--just to see how long I could survive. The speed in that level was of course way more than I could handle, and usually I'd be quickly overwhelmed. The best I could do, before completely losing control, was clear a few single lines (I don't believe that I ever cleared more than 10 lines in total). That was it. I was never able to put together anything resembling a skillfully played, sustained run. But I had a lot of fun trying to do so, at least.

And that's how it went. That was the kind of impact that NES Tetris had on my life. Nintendo's humble little block-dropping puzzler ate up just as much of my time as any of the year's big-budget games did.

In the following year, I returned to it less and less often, but not because I got tired of playing it, no. Rather, I'd been won over by another from its class.

At the time, I didn't see the point in owning a second version of Tetris. "Why would I waste time playing this when I already own a superior version of the game--one that has color and can be played on the TV?" I thought to myself as I looked over the game's box.

Also, I had better things to do with my Game Boy. I'd also gotten newer, more-interesting Game Boy games that year: Super Mario Land, The Amazing Spider-Man and Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Fall of the Foot Clan. And I got some new NES games, too. So my plate was full, and I just didn't have any desire to play a stripped-down version of an NES favorite.

Soon, though, my feelings changed dramatically. When I discovered the value of taking my Game Boy on the road with me, I started to see the appeal of portable Tetris. I found out that it was one of the best games you could play while on the road. It was the best company you could have when you were on a long car ride or when you got bored while you were visiting a relative's house. And for those reasons, I started to think that maybe Game Boy Tetris was actually the definitive version of the game.

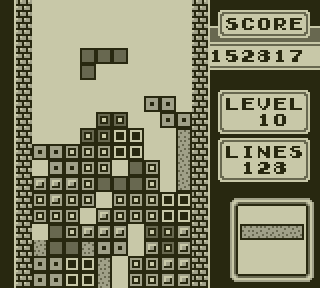

It also became my favorite version of Tetris. I liked it more than NES Tetris because its action didn't grow overly speedy until you reached Levels 17 and 18, and thus it allowed you to play longer and get more from each experience; and even then, its speediest teen levels weren't anywhere near fast as NES Tetris', so it was still possible to keep the action somewhat under control (my guess was that its high-teen levels were comparably slower because the Game Boy's processor couldn't handle hyper speeds).

And Tetris gained a new level of appeal to me when my friend Dominick got himself a Game Boy and began bringing it along with him whenever he joined us on a trip to Atlantic City or Long Island. That's when we got to enjoy one of Tetris' best aspects: its competitive multiplayer action. During car rides, we'd engage in animated, fiercely competitive Tetris battles and do so for hours (these were the only instances in which I ever put my link cable to use). And we had a ton of fun in the process!

I don't recall how our matches played out, no, but I'd guess that we went 50-50, since we were pretty even in skill. What I remember far more vividly were the cameos that were made by Mario and Luigi, who acted as the players' avatars. I was fascinated by their inclusion because, up until then, I didn't even know that they were in the game, and all I could think while watching them victoriously jump up and down and weep in defeat was that I was viewing content that only few were privy to. "How did Nintendo do this?" I wondered. "Is this hidden content somehow contained within the link cable, itself?" (Obviously I didn't yet have a good grasp on how video-game technology worked.)

So yeah--Tetris was the quintessential "road game." It made even the longest car rides fun.

Because Game Boy Tetris' action was comparatively slower-moving, I approached it in a different way. Mainly, I was more comfortable attempting sustained all-Tetris runs. Of course, such runs would usually end when I'd get to the upper-teen levels and the game would begin throwing out nothing but Z-shaped pieces, but hey--that was still much better than I fared in NES Tetris; in that version, I'd usually have to abandon my all-Tetris strategy and enter into survival mode during the early-teen levels.

What I learned about Game Boy Tetris while attempting all-Tetris runs was how completely nasty its piece-choosing algorithm was. Its rate for throwing out lines was ridiculously low (lower than even the NES version's), and in way too many instances, I'd go 30-40 pieces without seeing a line. Naturally this would always happen when I was in a desperate state. And when the line would finally show up, it would usually be too late; I'd have already plugged up the open column, or the stack would be so high that I wouldn't have enough time or space to flip to the line and shift it over to the open column.

For some reason, my yelling, "Give me a friggin' line already!" never seemed to help.

Otherwise, I sunk a fair amount of time into the game's B-Type mode, which was better than the NES version's, I felt. The only area in which it fell short was Level 9 victory screens. Disappointingly, none of them contained iconic Nintendo characters; rather, they contained only generic-looking humans (Russians, I presumed), which served to diminish the sense of reward. Nintendo's colorful characters were far more interesting than these faceless, interchangeable humans, and their presence was sorely missed (I figured that Nintendo axed them because the Game Boy's screen resolution was too low and thus it would be too difficult to squeeze 8 adequately sized Nintendo characters into a single screen).

Though, I was happy that Nintendo kept the "cowboy music." It was Game Boy Tetris' best musical theme, I thought, and I selected it almost exclusively.

Sadly, I was cut off from Tetris (and the rest of my portable library) when my Game Boy ceased operating after I neglected it for several years. I stupidly left the batteries in, and they corroded and thus destroyed the battery terminal. So I had no choice but to leave the game behind.

I didn't see Game Boy Tetris again until January of 2013, when I downloaded it as a 3DS Club Nintendo reward. Though, I didn't download it because I was interested in playing it, no. Rather, I did so on pure impulse and specifically because I was apt to download any Game Boy game with which I grew up (I was intent on putting the band back together and recapturing the past). My rationalization was that the game was only going to be available for a limited amount of time and then never again (because cheapskate Nintendo would surely let the license lapse), so it made sense to grab a copy while I could.

I had little interest in revisiting it because currently I had access to something better: the amazing Tetris DS, which had everything Game Boy Tetris had and so much more. "Returning to Game Boy Tetris would be an act of regression," I thought.

But when I finally got around to playing Game Boy Tetris, I quickly realized that I was wrong. It wasn't an inferior version. In, fact it was probably still the best version! Its action held up wonderfully because it was pure Tetris; it was tainted by "shifting," "hold queues" or any of that other newfangled nonsense that only served to rob the game of its most fundamental aspect: its spontaneity.

Game Boy Tetris didn't have Tetris DS' level of content, no, but it had something that I valued a lot more: original-style Tetris action. And that's why I started returning to it regularly.

Over the past few years, I've spent an enormous amount of time playing Game Boy Tetris. I've been returning to it almost daily. Its action never gets old; it's always the same great combination of fun and addicting.

Though, I'm finding that the game's piece-choosing algorithm is more hateful than I remember. These days, it seems even less inclined to give me a line when I desperately need it! Sometimes I'll go 50-60 pieces without seeing one. So any all-Tetris run winds up feeling more like a suicide mission.

Also, the algorithm seems to become more self-aware as the levels increase; by the time I reach, say, Level 10, it's able to observe the field and consciously, spitefully throw out pieces that it knows I can't use! Then, naturally, it finally gives me the piece I was begging for when it's too late for me to actually do anything with it!

It's that old man behind the curtain, I tell you! He's still out to drive me mad!

I have to say, though, that I have a greater appreciation for the game's visuals at this point in my life. I love that Bullet Proof Software, in response to the Game Boy's color limitations, designed it to where each Tetronimo has its own unique texture. Its doing so provided the game an unmistakable personality--one that helps it to stand out among the crowd even today.

I hold a special place for Tetrinet because it's one of the first online games I ever played.

At the time, of course, things like "servers," "proxies" and "IPs" were alien to me, so I left all of the client-connecting and setup operations to Mek, who regularly practiced that kind of sorcery.

On the surface, Tetrinet's action was very similar to Game Boy Tetris': Your goal was to outlast your opponents, and you could help yourself to achieve that goal by scoring multiple-line clears and filling your opponents' playing fields with junk blocks. Though, Tetrinet was a lot deeper than Game Boy Tetris (and other competitive Tetris games) because it included special items, which you could obtain by clearing away blocks that contained their corresponding symbols. Some special items were designed to help the player improve the condition of his or her field, while others were designed to hurt one or more opponents in some mean way. The "C" item, for instance, would clear away one line from the bottom of your field, whereas the "A" item would add lines to the other players' fields.

My personal favorite was the "S" item, which allowed you to switch fields with a competitor of your choosing. It was great because it helped you to dramatically improve your field's condition in an instant and, as a bonus, intensely annoy the poor sap with whom you switched!

We only played Tetrinet for a couple of weeks, but in that time, we engaged in many lengthy sessions and had a ton of fun. And I derived a lot of great memories from my Tetrinet experiences. I think about them quite often.

All I can say is that it was a pleasure to do battle with both Mek and Micah Cage, both of whom were fellow members of GX Entertainment--the most powerful force in online entertainment since that one guy who repeatedly spammed AOL Wrestling Chat with giant ASCII images of the Energizer Bunny.

I won't tell you that I was a Tetrinet savant, no, but I was pretty damn good at it. In that weeks-long period, I managed to amass a considerable amount of victories.

I scored the majority of my wins in honorable fashion and by using the most honest of strategies. And by that, I mean that I'd build a tall center stack and then use it as a support for a sloppily constructed V-shaped formation, and then I'd immediately switch fields with a player who was earnestly setting up for Tetris opportunities (whichever player wasn't a website owner who was currently providing me free server space). I'll let you decide as to whether or not that tactic was in the spirit of the Final Fantasy IV's battle music, which I used in place of Tetrinet's default MIDI theme.

Once everyone else started copying my strategy, things kinda broke down. That's about when our time with Tetrinet came to an end.

Tetris is timeless, and I'm sure that I'll be enjoying it, in one form or another, for as long as I live.

Tetris is important to me, also, because of how it helped to grow the puzzle genre, of which I was a huge fan. It inspired the creation of an exciting new subgenre and one that produced some of my all-time-favorite puzzlers--games like Dr. Mario, Columns, Yoshi, Wordtris, Lumines and Meteos. I continue to enjoy all of them, too.

But Tetris is still the best of its kind. It's still the most perfect expression of the block-dropping puzzle game. No other block-dropping puzzler (including any of its sequels or spinoffs) is in its league. No other can match it in terms of playability, longevity and ubiquity. It's one of the best video games ever made.

All I can say is thank goodness for Alexey Pajitnov, who proved that one man's contribution could do as much to change the course of history as any industry giant's. Using only the most basic of tools, he constructed a shining tower whose presence served to influence and enrich everything around it. And he created a foundation that was so solid that no force of nature could ever be strong enough to clear it away.

No comments:

Post a Comment