Absence makes the heart grow fonder, and that's why we were ecstatic about Nintendo's classic series returning in its beloved original form.

So eventually my attitude changed and I wound up becoming a pretty big fan of Zelda II: The Adventure of Link. As I played it more and more, I gained a greater appreciation for its unique visual and aural qualities and its radically divergent side-scrolling, combat-focused style of action, and ultimately I reached a point in which I was eager to celebrate its disparate take on The Legend of Zelda formula and declare its deviation to be a brave and successful act.

I was happy to say that I'd seen the light and that Zelda II was truly a great series game.

But back in 1991, that was far from the case. At that point in time, my relationship with the game was still in a very frigid state. I, like so many other of the neighborhood's kids, continued to perceive it as a weirdly aberrant series entry and speak of it as though it were an unworthy successor to the legendary original work. I was consistently repelled by its differences and always prepared to denounce them. And at all times, I was positioned at the frontline of the large group of people that was calling on Nintendo to correct its mistake and finally release a true follow-up to The Legend of Zelda.

We all wanted the same thing: a Zelda sequel that looked and played like the original. We desired for the series to return to form and offer us more of the top-down, exploration-based action that we so greatly enjoyed experiencing in the past.

That was all.

And in June of 1991, finally, our prayers were answered. Nintendo Power Volume 26 arrived with the unexpected news that a "Zelda III" was in development for the upcoming SNES! An enticing image of it was shown in the issue's "Super NES" preview feature. And it looked to be the type of Zelda game that we were all hoping for!

And in the next issue, more excitingly, the game was formally introduced in a surprise back-pages feature titled "Development Dispatch" (it got top billing in a showcase that also covered two other big games: Super Castlevania IV and Super Ghouls 'n Ghosts). The space dedicated to it contained two large screenshots and two giant paragraphs worth of preview text.

The feature was a total surprise because the issue's index, strangely, didn't make any mention of it. It came from out of nowhere! And that's what made its presence so shocking and exhilarating. Coming across it so suddenly was akin to opening up an unremarkable-looking box on Christmas morning and finding not clothes, as you expected, but instead three or four of the hottest games on the market. It was that thrilling.

The excitement of the moment was so great, in fact, that it stopped me from noticing that the accompanying information was mostly fluff. ("This game looks awesome!" was about all the piece had to say.)

But, really, I didn't care that the preview was light on details. What little it provided was still more than enough for me. I was completely engrossed by it.

In the days and weeks that followed, I read through the preview again and again, and each time, I intently pored over every sentence and drooled over every word. And during that stretch, I committed to memory every small detail about the game's reportedly massive overworld and its use of advanced technological systems. I'd think about said details constantly and extrapolate their meaning in the grandest ways.

What interested me most, though, were the preview's two darkly colored screenshots and its short plot summary, all three of which I found to be deeply entrancing and wonder-inducing. They inspired powerful visualizations that remained the source of my obsession for the next nine months.

I was especially happy to know that Zelda III's Link and Zelda were ancestors of The Legend of Zelda's main characters and that their tale of struggle would be playing out in a world whose structure was highly reminiscent of the beloved NES classic's. That, to me, was the best news possible. It confirmed that Zelda III would indeed play very similarly to the original game. And that's all that I desired to hear.

I left the rest to my imagination. I took what the preview gave me and used it as the fuel for my visualizations. I plotted out a whole world in my head: I envisioned a breathtakingly vast Hyrule whose landscape was formed from wondrously designed, interconnected labyrinths of 16-bit forests, mountain ranges, lakes, caverns and dungeons. And the information revealed in future issues of Nintendo Power helped me to fill in the gaps. It gave me an official title--"The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past"--and thus a theme to work with, and it explained to me the full scope of the game's newly introduced Light World-Dark World system, the description of which sounded amazing; it sent my imagination into overdrive and made me excited to think about the system and wonder about the affects it would have on the game's other aspects.

And these features and previews became some of my most-revisited pieces. I returned to them again and again, day after day, and I spent my time thoroughly examining and studying their detailed item listings, map illustrations, and interesting sidebar articles, which compared A Link to the Past with the original Legend of Zelda and did so for the purpose of explaining how the former evolved the latter's systems and mechanics. I loved everything about them.

The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past was the first SNES game for which I was super-excited. My hype-level was at a peak that hadn't been reached since the middle of 1990, when I spending almost every hour of every day dreaming about the upcoming Mega Man 3.

I couldn't wait to get my hands on this game and start exploring its world!

In the days before the game arrived in stores, there was the ever-present sense of anticipation that dominated our thoughts, influenced all of our daily conversations, and kept us in a constant state of excitement. On launch day, there was the celebratory atmosphere that permeated our homes as we unboxed the game and then enthusiastically and joyfully tore into it. And in the days and weeks that followed, there were all of the special moments and events that were inspired by our experiences with the game.

I recall how we'd hold daily conferences and talk about our rates of progress and all of the things we loved about the game. How, after separately completing the game, we'd play it together and jointly explore its freshly new incarnation of Hyrule and do so in the same way that we explored The Legend of Zelda's Hyrule many years earlier (in reality, it was only three or four years earlier, but to us, a bunch of early teenagers whose perception of time hadn't yet changed, it felt as though more than a decade had passed). How it felt so very appropriate for us to be immersing ourselves in the game's lush green world at a time when the season was growing warmer and our final grammar-school summer vacation was drawing near. And how its release coincided with our school's mid-April dance.

Oh, that dance. Talk about a weird night! I should tell you about it.

So around that time, our school's PTA, which was comprised of a tight-knit crew of mothers (and coincidentally the mothers of the kids from our graduating class), did something a bit unusual: Because it felt that we were a special group, it decided that the standard 8th-grade prom simply wasn't enough for us. We deserved more, it thought. So it generously set up its own fundraiser and used the money that it collected to book a special function for us. It was a "dance" that was to be held in advance of the traditional graduation events.

For me, this dance and A Link to the Past's release will forever be linked in my mind because of the weird thing that I did on the night in question: I decided, for whatever reason, to bring the game's instruction manual with me to the catering hall in which the event was being held (for most of the night, I kept it firmly tucked in my blazer's inner pocket)!

And whereas my classmates spent their time eating, dancing and conversing about their plans for high school, I spent most of the night sitting at the tables on the room's right side (the "boys' side") and re-reading A Link to the Past's manual and engrossing myself in its beautifully presented, fascinating backstory and its intriguing descriptions of occurrences like the creation of the Triforce; the people's desperate attempts to access the Golden Land; Ganon's conquest and the war that ensued; the arrival of the dark wizard Agahnim and the fallout that resulted from his mass deception; and how Hyrule's entire future hinged on the efforts of a single purple-haired hero.

I loved the idea that the outcome of a silently ongoing war--one whose corrupting influence was largely invisible to Hyrule's populace--was dependent upon the actions of an oblivious hero who couldn't have known that his efforts represented the last stand in a centuries-long battle whose vast canon entailed several large-scale conflicts between knights, monsters, gods and other magically inclined beings. It made the adventure seem so amazingly epic in scale and so incredibly consequential, and at the same time, it made me feel as though I was traveling through a world that was bursting with unseen activity.

A Link to the Past's Hyrule was alive and active, I felt, and its many spaces were rife with highly significant events that were occurring in both perceptible and imperceptible ways.

Though, I was a little cold on one particular aspect of the story: the humanization of Ganon, whose character, I thought, was being somewhat damaged by the Zelda team's depicting it as the unholy form of a mere "thief" named Ganondorf Dragmire. Making Ganon human in origin (and giving him a goofy name) only served to diminish his aura and make him seem less threatening than he was in the previous two games. It created the sense that he wasn't an innately powerful monster who was born from ancient evil, no, but rather some random guy who simply lucked into finding an artifact that granted him immense power.

But still, I liked what the team did with Ganondorf, and I especially liked what his actions did for the story. I felt that his sinister coup provided the game's narrative some real emotional weight and made its build-up feel all the more epic.

I loved the manual's storyline account in general. It was one of my favorite parts of the package. I read it so many times over that period that I almost managed to memorize the entirely of it (as well as the rest of the manual's text descriptions)!

And those were the types of thoughts that were popping into my head as I was reading through A Link to the Past's manual that night. I was completely engrossed by its fascinating storyline bits.

The problem was that the manual's text wound up distracting me from an unfortunate situation that had developed. While I was lost in my own world, my friend Dominick had become involved in a really bad altercation. He'd been turned down for a dance and cruelly rejected and mocked by a girl on whom he'd had a crush since 2nd grade, and he was understandably upset. And he loudly and angrily expressed his disgust over the matter.

Dominick was one of the smartest guys around, but, as I was aware, he lacked perception skills and thus didn't possess the ability to see people for what they truly were. So he'd always been blind to the fact that this girl, Tracy, was your typical rich narcissistic and the type of snob who would never even dream of condescending enough to acknowledge the existence of lowly plebs like us. He learned this the hard way.

In the following minutes, some of our male classmates tried to calm him down and console him, but it was no use. He couldn't let it go. He was too enraged by what Tracy did to him. It hurt him badly.

Eventually he got control of himself, but even then, his anger didn't fade. It continued to consume him. And consequently, he spent the rest of the night in a state of devastated silence.

His mother was my ride home that night, and let me tell you: That car trip was one of the most awkward I'd ever experienced. The whole time, not a single word was uttered. All three of us remained completely silent.

It's one of my greatest regrets that I didn't do anything to comfort my friend that night. I feel shame when I think about the way I reacted to the situation--how I decided to remain aloof and simply stand there and watch on from the sidelines. I should have been there for Dominick in his time of need. I should have done something to ease his pain. At the least, I should have confronted Stacy and told her off.

Sadly I didn't do anything of the sort. Instead I remained cold and distant. And I'll always hate myself for that.

But Dominick recovered pretty quickly. Within a day or two, he was back to his old self, and he was feeling pretty good about the state of things. He knew, after all, that we still had our Zelda and that plenty of great times were ahead!

And A Link to the Past certainly delivered on its promise. It was an amazing, magical game, and it made a profoundly positive impact on our lives. It consistently captivated and delighted us, it made our days brighter, it inspired some of the most fun group conversations we ever had, and it provided us many happy memories.

Miyamoto and friends' latest Zelda adventure was another top-shelf masterpiece, and we simply couldn't get enough of it. Its magnificently designed world of magic, monsters and mystery was an object of our fascination, and it remained so for the entire summer of 1992--our last summer vacation before the start of high school--and for many seasons in following.

A Link to the Past was our new obsession. We absolutely loved it. To us, it was arguably the best game ever made!

Like it was with Super Mario World, our observing and experiencing the game's advanced technological and graphical displays as they were described to us by Nintendo Power was an important part of the experience.

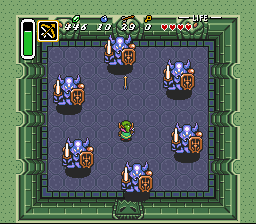

In our first play-throughs, we eagerly executed and triggered all such displays and marveled at them: We knocked a knight into a pit and watched on intently as he scaled down in size as he plummeted. We used Link's new spin-attack to joyfully tear up Hyrule Castle's plant life. We pulled up the game's fancy Mode 7-powered scrolling overworld map and entrancedly examined every inch of it. We feverishly picked up and tossed bushes, rocks, pots and signs. We watched on in amazement as Link hopped off of cliffs and dropped down to completely different environmental planes. We had fun mowing down strings of enemies with the Pegasus Boots' dash ability. And we entered into a state of gleefulness as we deflected Agahnim's projectile attacks back at him.

Each of these events and interactions represented an incredibly memorable first moment. And each would forever be regarded as an intrinsic part of our first play-throughs.

We were happy to say that the game's advanced graphical effects and mechanics worked exactly as advertised and were as impressive as we thought they'd be. And we understood their message: "A Link to the Past is a next-level video game," they said to us, "so get ready to go on an adventure that grandly transcends any other you've ever been on!"

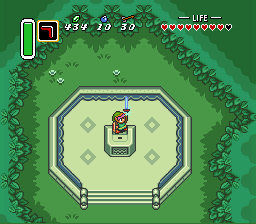

But for me, the single most memorable moment of the first play-through was something else entirely. It was an event that was more special than any other: my obtention of the Master Sword in the Lost Woods.

By that point in my life, I'd been playing video games for over a decade, and I'd experienced and witnessed a great number of emotionally impactful gaming moments. Though, none of them, I can tell you, were as powerfully moving, as inspiring or as gratifying as the moment in which I took possession of the Master Sword in A Link to the Past.

The scene in which Link pulled the sword from the stone pedestal and held it above his head wasn't very long. It lasted only about ten seconds. But for the entirely of that short time span, I was absolutely spellbound by what I was witnessing. I was hopelessly captive to all of the scene's powerfully stirring components and especially to its breathtakingly heroic ditty, which crescendoed in the most inspiriting and most epic fashion; as it played, its thunderous energy washed over every part of my room--my 20-inch television's crummy speakers unable to constrain its power in any way--and electrified the air around me and caused me to become covered in goosebumps.

And during those few fleeting seconds, I finally knew what it felt like to be a hero.

It was one of the most unforgettable gaming moments I'd ever experienced. I'd always vividly remember how it played out and how it made me feel.

My only disappointment was that the scene was over so quickly. I wished that it had lasted longer and given me more of an opportunity to savor its empowering influence and absorb its inspiriting energy. The only thing I could do, instead, was look forward to reliving that incredibly invigorating moment of triumph in a subsequent play-through.

Since then, I've procured the Master Sword in many a Zelda game, but never once have I witnessed a "Link takes hold of the Master Sword" scene that comes close to matching the power, the energy or the inspiriting influence of the scene that occurred when I pulled the Master Sword from its pedestal in A Link to the Past.

That's how special that scene was.

I'd like to spend more time talking about all of the other impactful moments and all of the wonderful memories that are attached to them, but I don't think that it would be wise for me to do so. If I go in that direction, all I'll wind up doing is making a mile-long list that contains pretty much every interaction I made over the course of my first play-through. And it would be silly for me to do that.

So I'll try to be succinct and tell you that I have, like I do with the original Legend of Zelda, at least one great memory attached to literally every screen, scene, visual effect, musical theme, character interaction and enemy encounter. I'm able to recall every moment of the adventure from the defining opening sequence, in which Link ventured forth into the rainy night and courageously defied the intimidating castle guards' orders as he searched for the distressed telepath who contacted him, to the climatic finale, in which Link destroyed the mighty Ganon with a final silver arrow and then proceeded to meet with the Triforce's essence and selflessly wish everything back to normal. And whenever I replay the game, I always make sure to stop and savor the many remindful recollections that pop into my head as I traverse and explore its beautifully crafted world.

And that should tell you everything you need to know about my A Link to the Past experience and how utterly indelible it was.

For years, A Link to the Past remained at the top of the list of games to which I returned on a frequent basis. On normal days, I'd play half of it in the afternoon (the Dark World's Swamp Palace was my chosen halfway point) and finish the final half at sundown, after dinner. On Sundays, I'd play through the entire game in one sitting and make an event out of the experience. And on some days, I'd play it with friends; we'd alternate control and each take a dungeon, just like we used to do whenever we played The Legend of Zelda together.

I'd even play it on the road. On the recommendation of my father, I'd bring my SNES with me to the Trotta's house in Long Island and play some Zelda in between dips in the family's giant backyard swimming pool. And the whole time, I'd remain deeply engrossed in the game.

I played through A Link to the Past so many times in those first few years, in fact, that I managed to map out the entirety of it in my head. I knew the locations of everything--every area, item, heart piece, character and cave. I memorized virtually every pixel of the Light and Dark Worlds. I was basically a walking A Link to the Past atlas. I knew the game like the back of my hand.

And for the longest time, A Link to the Past was a perennial contender for the top spot in my monthly "Top 20" lists (which were a feature of my personally crafted video-game-themed "Superbooks"). It never lost any of its luster. Year after year, it continued to prove to me that it was one of the best games of the 16-bit generation and more so one of the best games in history.

I loved looking at A Link to the Past's world just as much as I loved traversing it. It was a beautiful and entrancing place, and I found great enjoyment in immersing myself in it and intently observing its wondrous environments and soft-yet-vibrant colors and textures, whose hope-inspiring vividness that would manage to shine through even when they were rendering the darkest of dungeons, caves and wooded areas. I loved what those elements did for the game, and I always had fun absorbing and thinking about the messages that they were conveying to me.

Whenever I'd play through the game, I'd make sure to spend some time aimlessly wandering about the overworld and letting the sights enwrap me and shape my thoughts. It was an essential part of the experience, I felt, to gaze upon the rounded, fancifully designed trees; the imagination-stirring backgrounds (like the scrolling woods that can be seen from Death Mountain's heights and the Dark World pyramid's background, which contrasts the distant Tower of Ganon against a stunning sunset); the towering mountains; and the glowing lakes; and give myself over to them and invite their collective to tell its story and thus help me to form appropriately grand, breathtaking visualizations of game's world.

Because that's what A Link to the Past's version of Hyrule inspired me to do. It made me feel as though the best way to form a connection to it was to curiously examine its environments and settings and enthusiastically wonder about the type of atmosphere they were creating and the ways in which the actions of Link and Ganon's dark forces were impacting them.

That's what made A Link to the Past's Hyrule a true wonderland.

I was very fond, also, of the Light World-Dark World system. It was brilliantly conceived and executed, and it, more than any other game element, caused me to view A Link to the Past as a mind-blowingly next-level product.

I was amazed by the system for multiple reasons but mostly because it was a novel idea that had somehow already been fully realized. "How did Nintendo do this?" I'd often wonder as I was experimenting with the warp ability and, incredibly, seamlessly bouncing between two worlds that were similar in structure yet largely distinct in terms of their geological features. "How did the company nail a system this complex in its first attempt?"

I couldn't even fathom a guess as to how it happened.

And I can further contextualize the effectiveness of the game's Light World-Dark World system by saying that it's the only one of its type to ever capture me. None of the others that I've seen have ever impressed me or made me think that such a system could work as well a second time. The dual-world systems that I've seen in games like Castlevania: Harmony of Dissonance, Metroid Prime 2: Echoes, The Legend of Zelda: Oracle of Ages and The Legend of Zelda: Oracle of Seasons are, in contrast, mundane in implementation and execution, and I feel as though they exist merely to artificially extend game length.

The designers of those dual-world systems clearly didn't understand what made A Link to the Past's so appealing. They didn't grasp that a dual-world system only works to great effect if the separate worlds (a) connect in interesting and fun ways, (b) can be quickly and easily accessed and (c) aren't comprised mostly of areas that are merely pathways used for getting around each other's obstructions.

A Link to the Past's designers strongly understood those ideas, and that's why their Dark World-Light World system is, after 23 years, still the best of its kind.

Then there was the game's soundtrack, which was also outstanding. Its tunes were brilliantly composed and wonderfully vigorous in tone, but that, any listener could tell, was only part of what made them great. The tunes' other highly notable attribute was their special power: Each one of them had the ability to evoke strong feelings and emotions and put you in a certain state of mind.

The iconic Kakariko Village theme would allay my feelings of stress, provide me comfort, and fill me with optimism. The haunting, ominous Hyrule Castle and dungeon themes would heighten my feelings of apprehension and make the exploration element feel more dangerous and unsettling. The curiously quizzical theme that would play when you first entered the Dark World's Spectacle Rock area (as a bunny) would evoke a preliminary feeling of wonderment and temporarily make me feel at ease with its message that this newly traveled land wasn't quite as bleak as it appeared to be. And Dark World Death Mountain's harsh, foreboding march would make me feel as though I was being attacked from all sides, but at the same time, its urgent energy would animate me and motivate me to endure the storm and push forward.

In any play-through, I'd look forward to visiting the Lost Woods not just because I wanted to spend time observing its cool light-refracting graphical effect but also because I desired to listen to its mysterious, enchanted musical theme. I loved what it did for me--how it filled me with wonder and inspired me to think about what it would be like to visit fantastical places like the Lost Woods and the greater Hyrule. It, like so many of the game's other game's tunes, was powerfully alluring, and I didn't mind going out of my way to listen to it.

A Link to the Past's rendition was of the classic Hyrule theme was another superb piece of 16-bit music. It was exceptionally-well-composed, wonderfully orchestral, and incredibly rousing. In my first play-through, there were few moments quite as empowering as the one in which I first heard it--as the moment in which I exited the sanctuary and was immediately greeted by the most inspiriting, most resounding Hyrule-overworld variation that had ever been created. In that moment, I was more pumped than ever to start a Zelda adventure!

But I was even more in love with its mirror-world counterpart: the Dark World theme, which was special not just because it had the same type of booming energy but also because it was evocative in the most thought-provoking way. It was an emotionally complex piece; it was, all at once, able to evoke conflicting feelings of optimism, wistfulness, determination and despair, and thus it was absorbing and moving in the most wondrously curious way.

Any time I'd listen to it, I'd enter into a reflective state and spend a lot of time ruminating (sometimes agonizingly) on its meaning and trying to figure out what, exactly, it was telling me about the Dark World's reality. And all the while, I'd be filled with a feeling of deep yearning, though I could never find the words to articulate why that was happening (it might have been that the piece made me feel sad about the fact that I would never be able to physically visit a place as amazingly wondrous as the Dark World, or perhaps the piece filled me with feelings of longing because it so perfectly captured the essence of a deeply memorable gaming era that I couldn't help but feel was sadly fleeting).

In the current day, the Dark World theme still has that same power over me. It still evokes the same deep feelings and emotions. That's why I load it up on YouTube whenever I'm in a ruminative state. Its emotive energy helps me to distill my thoughts and flavor them and thus give them better context.

I listen to it, also, because it's one of the best, most stirring musical themes in gaming history. It's a legendarily great piece of music.

Though, the piece that touched me the most was the credits theme. It was a powerfully emotional, soul-stirring tune. It was very soft in tone, and it quietly and meaningfully expressed complementing sentiments of peaceful triumph and wistful plaintiveness. And thus it had the ability to evoke the most agonized of thoughts and contemplations.

Initially I was caught off guard by its presence because I wasn't expecting to hear such a melancholic tune after I'd just experienced an ending scene that worked so hard to uplift me and ensure that my adventure concluded on a high note. I thought for sure that an even more joyous and cheerful melody would accompany the closing credits. But instead I was met with a contrastingly sad- and sentimental-sounding tune, and I was so surprised by its presence that I didn't know how to react.

Before long, though, the situation changed. As soon as I decided to actually stop and listen to the tune rather than analyze it, it took hold of me and quickly allayed my feelings of confusion. And in that moment, everything started to make sense to me.

And as the tune absorbed me, my mood turned pensive and I began to fondly reflect upon my week-long adventure and recall all of its most memorable moments. The whole time, I let the tune's soulful notes color my thoughts and accentuate the impact of the scene's visual elements--the slowly rotating Triforce parts, the scrolling mountain background, and the dynamically changing skyline, all of which were incredibly evocative and effective at helping me to give a more solid form to the visualizations that were appearing in my head at the time.

I was sad that the adventure was over and that I could never again have a "first experience" with A Link to the Past, but at the same time, I was content because I felt that the credits theme was also speaking of future adventures in Hyrule. Long after the words "The End" appeared on screen, I continued to listen to the theme and let it inspire me to imagine what those adventures might be like. The resulting visualizations were glorious.

In my subsequent play-through, I made sure to tape the credits theme on my tape recorder so that I could listen to it whenever I was feeling reflective and allow it to guide my thoughts in all of the same ways.

A Link to the Past's tunes have since been remixed and rearranged several times over, but none of the resulting interpretations, I feel, can stand up to the original works. They're simply not as evocative or as deeply resonant as the tunes that were produced by that amazing, unmistakable SNES sound chip.

That should tell you everything you need to know about how great A Link the Past's original music is.

So yeah--A Link to the Past was a monumental, world-changing game. Its separate elements, much like scattered Triforce shards, came to together to form an awe-inspiring whole--a shining masterwork that was so grand in spirit, appearance and character that it was worth seeing and experiencing over and over again.

The game had some flaws, sure. The combat, at times, could be a bit sloppy. Some of the Dark World bosses could be beaten too easily. Allowing for Link to carry four bottles' worth of fairies and potions could trivialize certain challenges. And there were some rooms that were packed with more enemies than Link or the SNES could actually handle.

But in reality, those flaws weren't even worth talking about. They amounted to a small handful of barely noticeable surface blemishes. They could do nothing to hinder my enjoyment of what I knew to be a near-perfect video game.

And for years in following, A Link to the Past continued to provide me high-quality entertainment and inspire me in many ways (mostly it inspired me to creative). I returned to it on a weekly basis and did so eagerly because I knew that any play-through would entail four to five hours' worth of the some of the most fun, engaging gaming action that a player could ever experience. I simply couldn't get enough of what the game offered.

In that time, A Link to the Past became one of the most-replayed games in my entire library. I was around it constantly. And I never got tired of playing it.

What can I say? It was one of my all-time favorite video games, and I was always looking for the opportunity to spend time with it and enjoy its legendarily great action.

These days, I still feel the same way about A Link to the Past. I still regard it as an amazingly fun, high-quality action-adventure game and one of the best products the medium has ever produced.

I don't play it quite as often as I used to, no, but still I return to it fairly regularly, and each time I do, I have a grand ol' time, just like I did when I was a kid. And whenever I play it, I find that it hasn't lost a single bit of its magic. It's still able to do what it has always done: transport me into a world of imagination and wonder and remind me that video games are much more than simply a series of images on a TV screen.

That, I'm certain, is a power that it'll forever retain.

And what's also great about the game is its hidden depth, which I've been learning about for 23 years. In the mid-2000s, I discovered, through multiple sources, that you could use the bug-catching net to deflect Agahnim's projectiles! When YouTube came around, I watched play-throughs done by cool cats like BriSulph and NintendoCapriSun and observed that you could use magic powder on anti-fairies (which I've always called "bubbles") and turn them into normal fairies! And at some point, thanks to the Internet, I became aware that the platform near the cracked wall on Ganon Tower's third floor could be reached by dashing into the blocks on the adjacent platform (the impact propels you backwards and allows you to jump a tile)!

Hell--before seeing a recent Game Grumps video, I had no idea that you could carry a fish back to Kakariko Village and sell it to the bottle salesman! That's crazy!

And I'm sure that there are plenty of other secrets that I'm not yet aware of and that I'll be just as delighted to discover each one of them, too!

The only other thing I can say is that I'm glad that A Link to the Past has never been remade. It really doesn't need to be. It's perfect in its existing form. Attempting to update it would only result in its abandoning its classic early-90s-era values and losing much of what makes it so appealing.

A Link to the Past is a pure SNES game and should always remain as such.

Thankfully Nintendo resisted the temptation to remake it and chose a better path: honoring it by creating The Legend of Zelda: A Link Between Worlds--a direct sequel that builds on the original's template and gives you an opportunity to revisit its unforgettable world and traverse and explore it in fun new ways. It's a great series entry (despite its world design being overly derivative), and hopefully it'll bring in new fans who might wonder about the game that inspired it and promptly seek it out.

And should those new fans decide to take the journey of discovery, they'll no doubt come away with the opinion that A Link to the Past is one of the best video games they've ever played.

They'll understand why it's an essential piece of gaming history.

They, much like all of us, will see it for what it truly is: a portal into a timeless world of magic, mystery and wonder and a place in which one can create an endless supply of amazing memories.

I had a very similar anticipatory experience with Ocarina of Time - buying the game on day one (we preordered it and got the one with the gold cartridge), poring over the manual, having to wait through church so I could play it.

ReplyDeleteI also have fond memories of taking game manuals with me to school - probably to remind me of something comparatively stress-free. Symphony of the Night and Final Fantasy VII spring to mind.

As for LTTP, it was a staple of my childhood but I was a bit too young to experience it in the way you did. Certain parts were too difficult for me and it wasn't until I was a teen that I successfully completed the game.

Link Between Worlds has been my favorite Zelda game of the last generation, mainly because it combines the theme and feel of LTTP with the non-linearity and exploring aspects of the original LOZ.