Capcom's earthshaking masterwork completely transformed arcades and sent out reverberations that were so powerful that they deeply impacted every other sector, too.

Like I said in many of my previous works: I grew up believing that arcades, consoles and computers were completely separate entities that and that each one of them existed within its own independently functioning universe. I was aware that they shared a few odd ports of games like Donkey Kong and Mario Bros., yeah, but still my view remained that the industry's separate sectors were almost entirely incompatible with one another and that it didn't really make sense for them to share games.

"Games from one sector simply don't translate well to either of the others," I thought. "When a Commodore 64 game is ported to the NES, or vice versa, it's clearly stripped of the values that define it."

And it was that line of thinking that caused me to overlook the fact that the three sectors did indeed have a very obvious special connection: consoles and gaming computers were the direct offspring of arcades, and they were influenced by arcade gaming in a number of notable ways.

In truth, arcades were the place from which consoles and gaming computers inherited their values. They were the testing ground for the ideas and concepts that would invariably shape the direction of software-creation across all of the industry's sectors (including the future portable sector).

For emerging companies like Atari, Sega and Nintendo, arcades were the place to go when you desired to learn and grow and ultimately expand your business. They were the ideal setting for games that were designed to establish new brands and plant the seeds for future market conquests.

And in the early days, the aforementioned companies were quite successful in using such games to connect with consumers and drive their interest towards the companies' newly introduced home devices. People would go out and buy themselves Pong machines (or any of those shameless Pong knockoffs) because they remembered all of the fun that they had while they were playing the game with their friends at the bar. After being blown away by Space Invaders and Pac-Man, they'd eagerly anticipate a day when they could play either game from the comfort of their homes, and as soon as they learned that one of those games had become available for a particular console, they'd run right out and purchase both the game and the console.

Arcades were the place from which almost every major gaming trend originated.

I was oblivious to this reality because I had no real knowledge of arcade history. My entire frame of reference was derived from what I saw when I became a frequent arcade-goer in the mid-80s. At that point, arcades were very influential, but they weren't the main driver of innovation. Consoles, too, had a lot of sway, and they had, thanks to uniquely designed games like Super Mario Bros. and The Legend of Zelda, established themselves as an independent force. They weren't weren't reliant on arcade trends, and they were defined mostly by their own specially tailored games and their distinct hardware features. And the same was true with computers.

So the way I saw it, there was no clear connection between gaming's separate sectors.

That's why it was so amazing for me to behold what Street Fighter II: The World Warrior accomplished when it was released. It took arcades by storm and quickly redefined the entire arcade scene, and then it crossed over to consoles and reshaped that sector, too!

I'd never witnessed such a grand phenomenon

Really, Street Fighter II came from out of nowhere. Those of use who frequented the local arcades had never heard any news that such a game was in development or that it was going to be hitting the scene at any moment. We were completely oblivious to the fact that one of the most important games in video-game history was about to enter our lives.

To us, Street Fighter II's arrival was one of the biggest surprise events we'd ever experienced.

I remember how I found out about the game: I walked into an arcade one day and saw a huge crowd of people concentrated within its center portion--the space in which the newest releases were commonly positioned. The group that was surrounding the machine was so dense that it prevented me from even catching a glimpse of what it was playing and observing.

So I decided that the best thing to do was to make my usual rounds--spend some time playing WWF Superstars, Arch Rivals and some of my other favorites--and then come back later after the crowd dispersed a bit. "At that point," I thought, "I'll get a better chance of finding out what the big fuss is all about."

But when I returned about a half an hour later, the activity-level, to my great surprise, hadn't dropped at all. The machine was still surrounded by a huge crowd of people! So I had to settle for peeking through the cracks and observing what I could. And from what I could gather, kids of all ages were enthusiastically competing with each other in a game called "Street Fighter II" (I didn't notice that it had a subtitle, and for a long time, I remained unaware that it actually had one).

Later on, I was able to get a closer look at the game and see it in action, but I wasn't able to play it. I couldn't find the opportunity. There were simply too many people waiting for their turn, and I wasn't the type of person who had it in him to aggressively push his way through a crowd and jump to the front of it. So all I could do was watch other people play the game.

But as I left the arcade that day, I wasn't disappointed that I missed out on the chance to play Street Fighter II, no. In truth, I wasn't particularly interested in how it looked, and I wasn't even sure what type of game it was supposed to be. Back then, you see, none of us had ever heard the term "fighting game" before. There were only beat-'em-ups and brawlers (like Double Dragon, Ninja Gaiden and Street Smart), all of which invited players to team up and battle groups of CPU-controlled enemies. None of them were about players doing nothing but fighting each other.

"That's a really boring idea," I thought.

I came to that conclusion because I'd played the competitive modes in the NES versions of Trojan and Double Dragon--modes whose combat was close in style to Street Fighter II's--and I wasn't impressed with them. I found their action to be shallow and mundane. And I was certain that there was no way that modes of their type would ever be interesting enough to stand alone and become their own genre.

"One-on-one fighting modes just aren't that special," I believed. "They're fun for a couple of minutes at best. So there's no way that you could build an entire game around the concept of one-on-one fighting and expect it to find success."

And that's where my mind was at as I was thinking about what I'd seen from Street Fighter II.

All I could do was assume that I'd missed something. "Maybe it's a sequel to a game that had a different name," I theorized. "Or perhaps there was an original Street Fighter, but it didn't appear in arcades. It was instead an obscure Atari 2600 game or something."

Granted, retrospect has revealed to me that there were points in my life when I was completely oblivious and simply didn't notice that certain games existed, but in the original Street Fighter's case, I don't think that it was inobservance that caused me to miss it. It's more likely the case that I never saw a Street Fighter machine because the game had a very limited distribution and simply didn't appear in certain areas (like in Brooklyn, which was where I lived). I say that because none of my friends or fellow arcade-goers had ever heard of the game, either.

So it was as if an original Street Fighter never existed.

But really, though, we didn't dwell on the issue for too long. After we finally played Street Fighter II and discovered how great it was, we realized that its lacking a notable progenitor wasn't going to affect its popularity in any away. It was more than capable of standing on its own. It was a game that was so independently successful that it earned the right to scoff at ideas like "continuity" and "logical progression" and get away with doing so. Its power was such that it didn't need to adhere to any existing conventions.

And not only did it do an amazing job of standing on its own; it was able, also, to capture the imagination of the entire gaming populace and consequently earn itself the title of instant classic. (Furthermore it proved to me that my previous assessment was dead wrong and that one-on-one fighters were indeed substantive enough to be worthy of their own genre designation.)

And that's what the scene was like for many months in following: In every arcade I'd visit, all of the traffic would be centered around this one game, and players would never be able to make progress in the single-player campaign because they'd be too busy answering their fellow arcade-goers' endless versus-challenges. And the action would be wild and frenzied.

When I'd finally get a crack at the game, I'd never come close to reaching the boss-character fights because steady streams of patrons would continue to rush over to the machine with their quarters in hand and challenge me. And as always, they'd be prepared to furiously mash away at the panel's opposite half and do whatever it took to bounce me out of the competition. And if I wanted to last, I'd have to win every match in which I was involved. Failure meant having to give up my spot and spend the rest of the day as an observer. Because there was no way that I'd be lucky enough to get a second crack at the game.

That's what the atmosphere was like.

At that moment in history, Street Fighter II was the arcade experience. It was the only game that mattered. It was the main focus of every person who walked through the arcade's door. To the vast majority of players, no other game existed.

Well, at the time, the environment was so competitive that I was only able to enjoy Street Fighter II in short bursts (my sessions lasted two or three minutes at most), but still that was about all of the time I needed to conclude that the game was (a) worthy of receiving the highest marks in just about every conceivable category and (b) able to perfectly capture every bit of the essence that made the arcade-going experience so magical.

Street Fighter II was an all-around masterpiece: It controlled brilliantly. Its directional-input system, which would have sounded intimidating to me on paper, was incredibly intuitive and fun to exploit. Its action was briskly paced, highly engaging, and super-smooth. Its visuals were beautifully rendered, amazingly vibrant and richly detailed. Its awesome line-scrolling effects provided stages an engrossing sense of depth. Its fighting and movement animations were exceptionally fluid and dynamic, and characters' stringed combos were sometimes wonderfully symphonic in nature. And its striking and slamming sound effects had strong visceral appeal and the type of overpowering reverberance that helped the game to aggressively rise above the arcade cacophony and stand out in a big way (to me, this was an important attribute for an arcade game to have).

And yet it was the little touches that did the most to define the game's personality. I'm talking about the way in which the music would change in tone, increase in tempo, and become filled with urgent energy whenever one of the fighters' health meters was close to being depleted. How a round's finishing blow would occur in slow motion and the defeated character would dramatically hang in the air for a prolonged period before spectacularly crashing to the ground with violent, bone-crushing impact. How the match's winner would toss verbal jabs at his fallen opponent ("Seeing you in action is a joke!" one of them would say). And the announcer's iconic speech samples (like "Jah-paaaaan!" and "Round One. Fight!"), which would reliably infuse players with energy in both the pre- and post-fight periods.

Those were the elements that my friends and I would talk about most (and riff on most) after we were done playing for the day.

And Street Fighter II was that game. It was the trigger. Its very appearance sent a loud and clear message to arcade-goers of every stripe: "The next generation of arcade hardware is here," it said with powerfully momentous energy, "and your world is about to change in a big way."

That's what we felt when we played Street Fighter II and observed what it was doing for scene. We knew that we were witnessing a seismic shift in arcade entertainment.

And it was amazing to behold.

So yeah--Street Fighter II was a highly transformational game. It changed the entire arcade scene and took arcade gaming to the next level. We considered every aspect of it to be groundbreaking and revolutionary.

The only element of the game that really surprised me was the music. I honestly didn't expect it to be as great at it was. For as long as I'd been gaming, it had always been the case that brawling-type games had mailed-in soundtracks. Their music composers would consistently do what was customary and craft generic, largely indistinguishable hard-rock and heavy-metal tunes that were only there because they had to be. Because it had to be obvious to you that you were playing a totally rad game from the current era.

But Street Fighter II's music wasn't like that at all. It was distinctive, genuinely expressive, and very important to the experience. It had a higher purpose. It was there to tell meaningful, memorable stories.

Each stage tune, from what I observed, was specially crafted to describe the environment's character and thus convey to you the mood and atmosphere of the location in question and tell you something about the fighter that was associated with it. And I fully understood what each one of them was saying. I understood that Ryu's was a serious, no-nonsense school of learning; that Chun-Li's town was a perpetually active yet underlyingly peaceful place; that Ken's harbor was bereft of aesthetic warmth and welcoming only to those who possessed steely determination; and that Guile's air-force base was a battleground upon which only men of bravery could walk.

And I greatly enjoyed absorbing and thinking about the stories that these stage themes were communicating to me.

My favorite tune, though, was the one that accompanied the opening title sequence (in which a white-shirted fellow was seen punching out another fighter in advance of the camera's panning up to the top of a nearby building to reveal the game's logo). I liked it because it was a flat-out terrific intro theme, certainly, but more so because it had a deeply nostalgic quality to it--one that I struggled to put into words. The best that I could say was that it had a remindful aura whose spirit evoked memories of my greatest life experiences (especially those that were gaming-related) and thus filled me with positive energy, which I'd carry with me into action. (It could be, also, that the tune strongly resonated with me because I associated it with the halls and waiting areas of family's long-traditional hangout spots, across which it was always resounding.)

I was so fond of the intro theme that I made it a requisite to listen to it at least once before I popped in my first quarter. I knew that it wouldn't have been a complete Street Fighter II experience if I failed to do so.

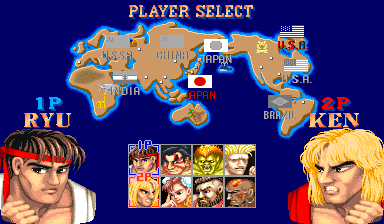

The game's cast was pretty special, too. It featured some typical gi-wearing martial-arts characters, of course, but it also included a number of unique and interesting fighters and a few that were so weird that I never imagined that I'd see characters of their type in a game like this one.

There was such a wonderful variety of characters. You had the electrically-charged man-beast Blanka, whose repertoire included ferocious attacks like scratching, biting and pouncing; the stretchy-limbed Dhalsim (or "Dahl-ism," as my friends and I repeatedly mispronounced it), whose legs and arms could somehow extend far across the screen (when I first saw him in action, I was certain that his ridiculous range would make him an incredibly cheap character, but when I tested him out, I discovered that his ranged attacks were actually a liability because they executed slowly and left him vulnerable to close-quarter strikes); the rapid-striking sumo E. Honda, whose inclusion, I believed, was a tribute to WWF wrestler Yokozuna; and the massive, menacing pro-wrestler Zangief, who became more interesting to me after I played Final Fight and realized that he bore an uncanny resemblance to Mike Haggar, who had become one of my new favorite video-game characters.

I'm telling you, man: I was fascinated with Zangief and Haggar's similarities. I was always thinking about them. In fact, I spent many school hours filling up my notebooks' back pages with features that theorized about the ways in which the two characters could possibly be related and with lists that meticulously compared their move-sets. And I was always hoping for the arrival of a game that contained both characters so that I could finally pit them against each other! (Such a game never arrived, so I had to wait an additional decade and settle for matching them up in the fan-made M.U.G.E.N.)

I didn't actually use Zangief, though, no. I didn't care to. I didn't like how he played. He was too slow and too big a target, which was a bad combination of qualities to exhibit in a fighting game, and all of his attacks had low priority. He was basically the game's worst character.

Rather, I stuck mostly to Ryu and Ken because their special attacks were easy to execute. The truth was that I had never become fully comfortable with arcade sticks (I was always more of a d-pad kind of guy) and I always struggled with arcade games that required precision-based movement; and that deficiency hurt me in Street Fighter II because it made it difficult for me to pull off attacks whose execution required the use of directional inputs. The only ones that I could execute consistently were half-circle and quarter-circle inputs, and Ken and Ryu's special moves just happened to use said inputs; and that's why I played as them the majority of the time.

I wasn't a fan of Dhalsim because his striking attacks were too weird (though, I loved spamming Yoga Fire and Yoga Flame). I generally avoided E. Honda because he lacked the quickness necessary to successfully leap over series of projectile attacks. And I stayed away from Zangief for all of the aforementioned reasons and also because he lacked a projectile attack, which was a big weakness to have in a game in which projectile-using characters dominated.

Those characters just weren't for me.

On occasion, I'd leave my safety zone and spend some time bouncing between Chun-Lu, Guile and Blanka, and I'd do so because those were the only other characters with which I felt comfortable playing. But as soon as anyone who possessed any actual skill showed up to challenge me, I'd immediately end my adventurous streak and go back to using Ken and Ryu and abuse my bait-jumps-with-Hadokens-and-punishing with Shroyukens strategy.

Because at the time, that was the only way I could win. I didn't possess the versatility necessary to reliably control the movements of and execute with other character types.

So yeah--I wound up liking Street Fighter II. I considered it to be a great arcade game.

And I got plenty of opportunity to enjoy Street Fighter II because it, like all of the other similarly influential arcade sensations, was everywhere. Machines bearing its name were showing up not just in every arcade but also in every corner shop, diner, bowling alley, amusement park, entertainment center, and movie-theater lobby. And it continued to draw crowds in ways that no other game could.

Everyone wanted to play Street Fighter II!

I remember how places like the driving range's arcade center would feature ten games, including hot new arrivals like Captain America and the Avengers and WWF Wrestlefest, yet nine of the machines would continue to remain unoccupied, and all of the visitors would spend their time lining up at the Street Fighter II and eagerly waiting for the opportunity to challenge the spiky-haired jackass who had been doing nothing but spamming Yoga Fire in the half hour that he'd been there.

That's how much of a draw the game was.

Street Fighter II was on the minds of kids everywhere. You couldn't go anywhere without hearing about it. Its popularity generated endless amounts of discussion in every school and every neighborhood hangout. Its power influenced the way we conversed, bantered and interacted.

For the entirety of that era, it was a popular thing for us to mimic the characters' moves while loudly shouting out the associated voice samples (like "Haaa-doooo-ken!", "Shrooooooy-yuken!" and "Sonic Boom!"). And it was common for us to randomly utter the announcer's famous quotations and pronounce country names the same way he did. We were always referencing the game in some way.

Our teachers weren't thrilled by this behavior, of course. They were never impressed when random cries of "Ti-gerrrrrr!" would suddenly echo throughout the hallway during class time. They didn't find it quite as hilarious as we did.

Street Fighter II's popularity was so great that arcade-goers across the world demanded more of it. It was said that fans had written to Capcom and swamped it with requests for a new version of the game in which it was possible to play as the boss characters, three of which (Vega, Sagat and M. Bison) players dreamed of taking into action (no one cared about ol' Balrog because his move-set and fighting style were so uninteresting).

And I remember how astonished we were when the new version, Champion Edition, started appearing in arcades so soon in following. We couldn't believe that it was possible for a company to respond to fan requests so quickly! (We didn't consider the possibility that Capcom already had the updated version in the tank and was just waiting for the right opportunity to release it.)

And Champion Edition met all of our expectations. It was exactly what we wanted it to be!

And I can't stress enough how mind-blowing it was to play as the seemingly overpowered boss characters. It felt almost taboo. It was like we were breaking the rules in an extreme way. I mean, there was literally no other game in which you could play as bosses--the types of characters who came equipped with two sets of projectile attacks and near-undodgeable flaming-torpedo charges.

You could even climb on the fence in Vega's stage! "How mind-blowingly awesome is that?" I thought to myself. Being able to interact with a stage in the way that bosses could was surreal to me. I loved that you could do it!

Thereafter, all of the time that I spent with Street Fighter II was dedicated entirely to playing and experimenting with the boss characters and particularly Sagat (who, we would always joke, was probably related to Full House's Bob Saget) and M. Bison. They weren't as overpowered as I was hoping they'd be, which is to say that had nowhere near the amount of priority and striking power that their CPU-controlled World Warrior forms led us to believe they possessed, but still they were highly appealing characters and I loved to play as them. All of their moves were just plain fun to use!

That was all there was to it.

But even then, I continued to think highly of Street Fighter II. I considered it to be an awesome arcade game. That's why I treated it as huge news when Nintendo Power announced that Capcom was bringing the game to our 16-bit consoles. "This is a monumental event," I thought, "and one of the biggest things to ever happen in gaming!" I was really excited about the news.

And I wasn't the only one who felt that way. Every kid in my neighborhood was hyped for the announcement, and pretty much everyone who owned a current console was planning to buy the game the moment it arrived in stores. Most people were aiming to get their hands on the SNES version because Nintendo had secured timed exclusivity for the game and because they were ravenously hungry for a home version of Street Fighter II and needed to get it as soon as possible.

Of course, all of my SNES-owning friends were in that group.

And the game coming to consoles was great for me, also, because it meant that I could now completely avoid the arcade versions, which had since become a horror to play. By the middle of 1992, the Street Fighter II arcade scene had changed for the worse and was no longer welcoming. It had become hyper-competitive, and it was now consistently drawing in psychos who liked to violently slap the machine's siding as they played and scream at the monitor when things didn't go their way; and I had no desire to be around those types of people.

Also, I started to get confused by all of the new revisions and their many mechanical alterations. "What's the difference between 'Hyper' and 'Turbo'?" I struggled to understand. "And what the hell is a 'Rainbow Edition," anyway? A more colorful version?!"

I felt as though the scene had transformed into something entirely different and I'd been left behind.

And when the plainly named Street Fighter II finally arrived, it was everything that I hoped it would be. It was a highly accessible, easy-to-play version of the arcade classic. That was all that I desired.

And this was the period in which I became quite a formidable Street Fighter II player. Truthfully, it was easy for me to do. I wasn't a master of fighting games by any means, no, but I'd always possessed a natural aptitude for them, and thus I was able to pick them up quickly and hold my own against even the most skilled of players. And that innate ability helped me to become one of the best Street Fighter II players around.

In the early days, I played it safe, as I had in the past, and mostly split my time between Ryu and Ken, but after I became more comfortable with the game, I gravitated more toward Blanka, who I felt had greater potential. And once I unlocked that potential, I started using him exclusively; and soon I developed strategies that helped me to win at a very high rate. (My favorite trick was to surprise an opponent with a horizontal rolling attack right at the match's start. Most people weren't aware that you could begin charging attacks during the announcer's countdown, so they weren't expecting me to come out of the gate with a time-dependent attack!)

Sadly, I don't have any other standout memories of my time with the original SNES version of Street Fighter II. I spent the majority of it engaging in standard hours-long sessions in which I battled my friends over and over again, and naturally my memories of those experiences blend together.

The only other thing that I'm able to recall is the shockwave that ran through the scene when Nintendo Power arrived with news of a secret code that allowed two players to select the same character. "Here's a chance for us to break another longstanding taboo!" we were excited to think. It turned out, though, that doppelganger matches weren't quite as interesting as they sounded in print. In reality, they were kinda dull.

Oh well.

For a long time, it seemed, I was the only one who didn't own a copy of Street Fighter II. I didn't feel that I needed to because, like I said, all of my friends owned it, and thus I had convenient access to it. I could play it my friends' houses pretty much anytime I wanted.

But my feelings changed when Street Fighter II: Turbo was announced. It was said to include the four boss characters as playable fighters, and that excited me because I loved playing as the boss characters (well, all of them except for Balrog). I saw their inclusion as a major selling point. I saw it as a reason to own a version of Street Fighter II. "These are true 'special characters,'" I thought, "and it'll be great to be able to spend time playing as and experimenting with them in the comfort of my own home!"

The allure of being able to engage with a Street Fighter II game in that fashion was just too great to resist!

And if I owned this new version, I also thought, I could get one up on my friends! "So what if they own a version in which you can play as the original eight characters?" I said in a cavalier way. "I'm going to have something better: a version in which you can play as all of them and the four bosses!"

I'd be the envy of the neighborhood, I believed.

But, well, things didn't work out like I thought they would. All of my friends wound up buying the game, too, so I wasn't able to gain the special distinction I desired.

Honestly, though, I didn't mind that all of my friends also owned the game; it was a great, actually, because it served to expand the amount of places that I could go to and achieve victory by spamming Tiger Shots and Psycho Crushers!

Playing alone wasn't as much fun as I thought it would be, sadly, but still, having my own copy of the game was beneficial because it gave me the opportunity to become more intimately familiar with the game's narrative, mechanical and musical elements. I now had all of the time that I needed to (a) read through the manual and learn about the characters' backstories (and finally find out who the copycat Zangief truly was) and use that information to put together theories as to how the Street Fighter series was connected to Capcom's other combat-focused games; (b) hone my skills by fighting the highest-level CPU opponents; and (c) play around with the "Music Test" and listen to the game's outstanding tunes (and especially its surprisingly excellent credits theme, which I could now enjoy to the fullest because it was, in this form, free from the interference of accompanying grunting and striking sounds).

And furthermore, I was able to better absorb and appreciate the sheer breadth of Street Fighter II's content and see just how truly transcendent the game was. Here I was, I understood, playing a game that had completely transformed the arcade scene and was now doing the same to the console space. It was the driving force behind one of the most amazing, awe-inspiring revolutions the medium had ever seen.

And I felt lucky to be a part of it.

And for the rest of the 16-bit era, Street Fighter II continued to hold a top spot on our list of multiplayer favorites. It was up there with beloved games like Altered Beast, Golden Axe, Super Mario Kart, Streets of Rage, Final Fight 2 and Saturday Night Slam Masters; and it was, like each one of them, a game to which we returned on a regularly basis. We engaged in marathon Street Fighter II sessions at least once a week (usually on Saturdays).

We simply couldn't get enough of the game's action. It was so addicting!

And as it was with every other multiplayer game, my best memories of Street Fighter II come from the times in which my best friend, Dominick, and I enjoyed it together. One of the memories that I most fondly recall is the one in which Dominick almost lost his mind while trying to beat the game.

I vividly remember the scene: I arrived at his house, one day, while he was in the middle of a self-imposed challenge to beat the game on the highest difficulty-level, and I watched on as he made it to M. Bison without breaking a sweat. At that moment, he was feeling pretty good about himself.

And that's when the trouble began.

Basically he struggled mightily with the Bison fight. For about a half hour or so, he failed to secure victory, and in that time, he experienced a wide range of negative emotions.

What was bothering him most was that every match playing out the exact same way: He'd absolutely dominate the first round and win without taking a single hit, and he'd perform very well in second round only to the point in which he got Bison down to a sliver of health. At that moment, Bison would mount his patented superman comeback. It would go like this: head stomp, flying fist, Psycho Crusher, throwing move, round over. Bison would then easily take the final round.

With each failure, Dominick grew angrier and angrier, his teeth clamping ever tighter and his mutterings growing louder and increasingly unhinged ("Yeah? Yeah?" he'd say to himself in a hushed, grumbling manner. "Is that how you want to play? OK--we'll see! We'll see!"). And as the losses piled up, he began shifting closer and closer to the TV, and he made sure to lean forward so that the apparently sentient SNES could more easily discern his serious threats.

At one point, he promised that he would destroy the console and the game pak with his bare hands if they didn't start to cooperate with him and allow the match to play out like he wanted it to. Additionally, he swore that he would become a game programmer and do so for the express purpose of hacking Street Fighter II's files and deleting all of the data related to M. Bison.

Unfortunately for him, though, neither the game nor the SNES was moved by his threats.

Dominick then began to furiously stomp his around the living room and irately complain about the game and its creators. His tantrum included a new threat: He said that he was going to fly to Japan and hunt down and confront the Capcom employees who made the game! To keep up the act, he stormed into the hallway and plucked out the White Pages, then he brought it back to the living room, slammed it down on the table, and began to flip through it in a crazed fashion and do so without any idea of what he was actually looking for.

At that point, I'd seen enough to know that it was time for me to go home. "This guy's going to be angry the entire day," I thought to myself, "so I'm probably not going to have much fun if I stick around."

So I don't know how the story ended. I like to imagine that Dominick did fly to Japan and confront one of the game's designers and that the designer, naturally, responded by delivering a head stomp, a flying fist and a Psycho Crusher before launching Dominick through the Capcom building's glass door with an over-the-shoulder throw.

Because I like fun.

My other standout memory is of the near-friendship-killing conflict that occurred as we were playing Street Fighter II: Turbo. I remember how and why the conflict brewed.

The problem started because Dominick knew that I was the better Street Fighter II player (only by a little) and he wasn't happy about that. One day, he decided to express this sentiment during a stretch when we were engaging in a series of bouts and continuously matching up the same two characters. I kept using Chun-Li, and he kept using Guile.

During one round in particular, he got pissed at me because I caught him with two or three air-throws in a row (when all I was trying to do was land simple jumpkicks) and because he hated being beaten by such moves. To him, throwing moves of any kind were "cheap"--especially so when they were executed multiple times in succession. In subsequent matches, I tried to refrain from executing air-throws because I was aware of how much their use upset him, but I wasn't able to do so. I kept executing the move unintentionally. And each time it happened, Dominick's blood pressure shot up a little more.

I plead my case. I told him that all I was trying to do was deliver standard aerial strikes and that the throws were occurring inadvertently. But he didn't believe me. He was certain that I was doing it purposely--that I was intentionally trying to cheat him out of victory. And as we played on, he continued to accuse me of relying on "cheapness" to win. Before long, his entire commentary started to consist of a single word. All he kept saying was, "Cheap! Cheap! Cheap! Cheap! Cheap! Cheap! Cheap! Cheap!" (and I'm certain that he wasn't trying to create a new type of exotic bird call).

After losing several matches in a row by virtue of being hit with my unintentional air-throws, he'd had enough. He lowered his controller to lap-height, and then he turned to me with an angry scowl on his face. And the meaning of that angry scowl was clear to me: It was a challenge. It was an expression that said, "My character, Guile, also has a midair throwing move, so let's continuously leap toward each other and see who has the superior air-throw game!"

At that point, I was tired, and I didn't want to play anymore, but I decided to acquiesce because I felt that he would drop the issue if we played a round in which he was able to get in some throws. Then, I thought, he'd calm down and agree to move on to some other activity.

Now, I swear this to you: I had no knowledge of how air-throws were triggered, and certainly I didn't possess the skill necessary to pull off strings of them with consistency. In that next match's opening round, all I did was jump forward while holding left on the d-pad, and it just happened to work out that every one of our rapidly occurring air engagements resulted in Chun-Li slamming Guile to the ground. Quickly the round was over, and I was declared the winner.

And it happened so fast, really, that I had no time to digest what had just transpired. So I continued to stare at the TV screen blankly.

But Dominick didn't share our opinion. When we started laughing, he absolutely lost it. He shouted "That's it!" and then yanked the SNES off of the entertainment center's shelf (again) and left the game in an unplayable state. He then began to stomp his way around the house and loudly rant about his alleged superiority. He told me that I wasn't as good a player as I thought I was. He said that I was only capable of earning "cheap victories" and that he'd win every match if throwing moves didn't exist. He pretty much inferred that I was a cheater.

Well, I couldn't stand to be berated like that, so I decided to follow Joseph's advice and head home. (Joseph had witnessed many of Dominick's outbursts, and thus he knew that there was no way to immediately calm him down. He pulled me aside and said, "He's going to be like this for a while, so you should probably go.")

After the incident, Dominick and I didn't talk again for a long time.

We eventually made up, of course, but we did so under a special condition: "The best way for us to remain friends," we said, "is to never again play against each other in Street Fighter II!"

Good times, I tell you.

At one point, I decided, for whatever reason, that I needed to own all three SNES versions of Street Fighter II. "It makes sense to have all three of them in your library," I thought to myself. "I don't know why, exactly, but it does."

The first thing I did was buy Super Street Fighter II the week it released.

And, well, I immediately regretted doing so.

I didn't feel that the game was bad in any way, no. It was just that I didn't find the four new fighters (Fei Long, Cammy, T. Hawk and Dee Jay) to be all that interesting. And what made the situation worse was that none of my SNES-owning friends were interested in playing a new version of Street Fighter II. So I was stuck with a game that I had no motivation to play.

A couple of months later, my brother, James, handed me a list of games that were available at his friend's store, which was clearing out its SNES inventory, and asked me if I wanted any of them. The original Street Fighter II was on the list. So I requested that he pick it up for me.

Doing that, I quickly realized, was a mistake. The game had nothing to offer me. I played it for about five minutes and then promptly abandoned it when I suddenly remembered that I owned a superior version of Street Fighter II.

The game only cost me a few bucks, so there was no real harm in buying it, but still I felt icky about buying a version of Street Fighter II that was vastly inferior to the two that I owned. I knew that it was a stupid thing to do.

So, really, both purchases were misguided. I should have just stuck with Turbo edition, which already had enough content so satisfy me.

I understand, now, why I decided to buy the other two versions of the game. I did so because I felt as though Street Fighter II was so incredibly great that it deserved to be enjoyed in multiple formats. It was worth owning multiple versions of Street Fighter II simply for the purpose of seeing how its groundbreaking gameplay evolved and how its outstanding aural and visual elements translated to each platform.

I'm sure that the aforementioned is true because it's exactly the reason why I went out and rented Special Champion Edition during the year-and-a-half-long period in which I owned a Genesis. I wanted to see what it was. I wanted to find out what Street Fighter II looked and sounded like on a Sega console and what the Genesis' specifications inspired Capcom to add to the game.

And I was pleased by what I saw. Special Champion Edition was a great version of the time, and I enjoyed the time that I spent with it (I kept it for over a week!).

I didn't like that you had to press the Start button to switch between punches and kicks (the six-button Genesis controller, as far as I'm aware, wasn't available yet), but otherwise I was impressed with everything the game did. I was especially fond of its interpretations of the stage music and particularly its rendition of Guile's theme. I found the piece so striking that I would turn the game on and start up a two-player match in the air-force base just so that I could listen to it!

It was (and still is) my favorite version of theme.

And, really, what says more about Street Fighter II's influence than the fact that it forced Sega, a major hardware manufacturer, to introduce a new six-button controller during the middle of a console generation? "If you don't put more buttons on that pad," the game told Sega, "you'll never have a truly competent version of me, and you won't be able to ride the wave that I'm creating. You'll be left behind."

Street Fighter II created a new reality and put Sega in a position in which it had no choice but to adapt. That was the type of power it possessed.

(On an aside: We loved Street Fighter II so much that we couldn't wait to see the film adaptation of it. We did so in December of 1994. We took our friend Steve to see it during the week of his birthday. It was our gift to him.

And, well, that's pretty much all I care to say about the experience. Thanks for stopping by.)

It was an amazingly transformative game.

For me, Street Fighter II was the only fighting game that really mattered. It was incomparable. No other fighting game could match its quality or capture my interest in the same way. It was the best of the best. It was, on almost every occasion, the first game to which I would turn whenever I was hungry for some fighting-game action. It was the only one that could truly satisfy my craving.

I mean, I enjoyed playing some of its derivatives, like Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Tournament Fighters and a few of the SNK fighters, but the fact was that none of them could come close to reproducing its magic. For that matter, I found Street Fighter II to be infinitely superior to Mortal Kombat, its closest competitor, whose action was, in comparison, bland- and homogenous-feeling; to me, its fighting system had little appeal beyond fatalities.

Street Fighter II was, quite simply, the undisputed champion of fighting games.

I'm writing this piece just a few days after the series' icon, Ryu, was added to Super Smash Bros. for Wii U, which I consider to be an extremely exciting to development. I don't play the game much anymore, no, but still I'm thrilled to see Ryu in there mixing it up with with Pac-Man, Mario, Donkey Kong, Link, Samus, Sonic, Mega Man and many of his other fellow gaming legends. He's where he deserves to be.

I have to say, though, that it's actually kinda surreal to see him featured so prominently in a series that was originally created for people who were too intimidated by "serious" fighting games like Street Fighter II. His inclusion could only be said to represent a shift. It tells us that Smash Bros. has evolved significantly since its early days and has grown in such a way that it now eagerly embraces a broader diversity of gameplay and aspires to become more compatible with the types of games it used to spurn.

And as a result, two of the world's biggest fighting-game franchises are finally able to intersect. And I love to see it.

At the moment, it doesn't appear as though Ryu is going to make it to the top of competitive players' tier lists, but, honestly, that's OK. Where he falls on some arbitrarily created list doesn't really matter. The important thing is that he's in the game. It's that we can now match him up against Mario (his Smash Bros. analog), Captain Falcon, Ganondorf and all of the game's other iconic video-game characters. That's the true appeal of his inclusion.

I'm just happy that Masahiro Sakurai and his team finally found a fitting way to honor the game that clearly inspired their prized franchise!

And honor it they should. Street Fighter II is one of the greatest, most amazingly influential games ever created, and it deserves all of the reverence and adoration it gets. The entire gaming world is a better place because of it.

For me, Street Fighter II did a number of important things: It revitalized my beloved arcades and made me more excited to visit them. It provided me some of the most fun, intense gaming action I'd ever experienced (and it still does so today). It helped me to form closer bonds with my friends and classmates. And it opened my eyes to the fact that the medium's different sectors (arcades, consoles and computers) weren't actually fragmented--that, rather, they had a strong synergetic relationship and were always influencing each other in significant ways.

So I owe a lot to Street Fighter II. It had a profoundly positive impact on my life, and it helped my favorite medium to evolve and grow and enjoy a better future.

It was truly the shaper of worlds.

If it were possible to write it a letter of admiration, I'd do so, and I'd express my thoughts with what I think are the three most appropriate words:

No comments:

Post a Comment