How a bunch of garage developers used their teleportation powers to reach across the console-computer divide and pull me into their world.

In the early-to-mid 90s, I wasn't the enthusiast that I should have been. For as much as I would have liked to claim that my being around the Commodore 64 for several years meant that I was well-informed about the state of computer gaming, the reality was that I knew practically nothing about the scene. I couldn't have told you what the competitive landscape looked like, how computers had evolved technologically since the 80s, or what any of the current platforms' hottest games were.

At the time, I would have assumed that the scene had remained static and that the Commodore 128 and the Amiga (neither of which I'd ever actually interacted with) were still dominating the market and doing so on the back of the same types of games that had always been associated with their sort (bizarre platformers, text-heavy adventure games, and intimidatingly complex strategy games).

Because that's where my mind was at. "I can't imagine that anything truly groundbreaking is happening over there," I was consistent in thinking.

And because game magazines had pretty much stopped talking about computer gaming, my perception was that computers weren't even relevant anymore. It must have been the case, I thought, that computers had now fallen well behind arcades and consoles in terms of their ability to spark industry-shaping movements.

I was living in a bubble, basically.

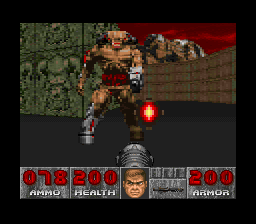

That's why I was so surprised by what my brother, James, told me about Doom--his latest SNES purchase. He informed me that it was a new type of three-dimensional shooter that started its life as an independent game that was designed for play on PCs.

Though, honestly, I couldn't imagine that such a feat was possible given what I "knew" about computers. "Are Commodore computers really advanced enough to play host to such a game?!" I wondered in a skeptical manner.

And what I saw from Doom only heightened my skepticism of James' claim. What I was witnessing, I was sure, was the gameplay of a mind-blowingly large production that was brought to us by a team of experienced industry veterans who were representing a distinguished, resource-rich development house (the esteemed-sounding "Williams Entertainment," whose name appeared on the game's box) and certainly not of an "independent" game made by a bunch of teenagers who were working out of a garage somewhere in the middle of suburbia.

"Only big companies can make games that look this amazing!" I felt safe in concluding.

And I remained stuck in that mindset for quite some time. It would be years before I'd learn of id Software's existence and come to understand the significance of independent developers and how important their contributions were to the medium. (It helped, also, that I finally learned the difference between a developer and a publisher.)

Sometime during the intervening period, I grew tired of watching TV and working on my art projects, and I formulated a plan to sneak downstairs and hastily intermingle with James' friends and thus prevent him from spotting me and kicking me out.

Unfortunately, my plan didn't work. He saw me creeping down the stairs and proceeded to bring attention to my presence. But this time, surprisingly, he didn't kick me out. Rather, he let me stick around as an observer because he was keen on the idea of impressing me with the new game that he bought earlier that day.

The game in question was called "Doom," which he alleged was a big-time SNES release. And that seemed odd to me because I'd never heard of it or read anything about it. I couldn't recall seeing it in Nintendo Power, which, I was certain, would never ignore a big release. (Though, I did consider the possibility that I simply missed it because of my tendency to ignore games that weren't directly in my interest.)

At first glance, Doom appeared to resemble one of those boring 3D dungeon crawlers (like Eye of the Beholder and Might and Magic II: Gates to Another World) that James and his friends seemed to enjoy so much, so I was quick to write it off as nothing interesting or special. Because I just didn't like those kinds of games.

I mean, I felt that the technology that developers used to achieve pseudo-3D visuals on consoles like the NES and SNES was cool and all, but I had a problem with the types of games that it powered. They were just too repetitive and too plodding for my tastes. (Though, I'd probably love them now.)

But when I actually started paying attention to the action that was occurring onscreen and allowed my senses to operate free from bias, I came to see that my assessment was incorrect: Doom wasn't a generic dungeon crawler. It was something completely different and, in fact, unlike anything that had ever existed before!

The more I saw of Doom, the more fascinated I became with how it functioned. It was just as James explained it to me: Doom's 3D spaces weren't formed simply from a series of static images strung together frame by frame to create the illusion of depth, no; rather, they were free-flowing, and they could smoothly scale and rotate around the player and do so as if they had actual dimension to them! Thus their every hall and corridor could be explored from every angle and every direction!

"That's incredible!" I thought.

What was wild, too, was that the invading monsters also had physical dimension to them. Their heights would gradually change as you moved toward and away from them, and the shelling damage that you inflicted upon them would change in severity depending upon how close you were to them at the time. Just like in real life!

You could track a monster's every movement even if it was maneuvering about somewhere far off in the distance, and it was possible to engage with it even if only a single pixel of its elbow was currently in view! And when monsters were present but not directly in view, you could tell that they were there because you could hear their snortling, which, unnervingly, emanated from beyond the walls and from the unseen spaces in which they were likely lying in wait!

James told me that if I listened closely, I could even determine the direction from which the snarling and roaring sounds were originating!

"This is unreal!" I thought to myself as I observed what Doom was doing.

At the time, I was perplexed by the game's technology, and I wasn't sure how a 16-bit console could produce such advanced effects. "Could it be that 'true 3D gaming' was achieved when I wasn't paying attention?!" I wondered. "And now it's actually possible to make 3D games on consoles?!"

I mean, I knew about Star Fox and the Super FX chip, sure, but Doom seemed to be doing things that were far more advanced than what their combo was capable of producing. It was rendering much more than a couple of simple cubes and polygonal archways. It was displaying elaborately sized, multi-dimensional stage constructions that made Star Fox's plainly designed, texture-less structures look primitive in comparison!

"The game has to be using some next-level technology!" I thought.

So yeah--I was blown away by what I was seeing!

And it would be a crime for me not to mention how big a role Doom's music played in helping the game to create an amazing first impression. The game's menacing, deeply toned tunes produced a powerful reverberance that pervaded the basement's every space and influenced our surrounding atmosphere. It created a palpable unease for both player and observer alike and made us feel as though the basement, itself, was an extension of the game's world.

It was that immersive.

I was only a viewer, yet the music's ominous vibe and the monsters' distant rattling filled me with the same feelings of tension and anxiety that haunted the player any time he was slowly and cautiously easing his way toward the end of a dark hallway.

I found myself absolutely gripped by Doom's music and sound qualities. They were amazingly entrancing and immersive!

After watching James and his friends play the game for ten minutes or so, I decided, for whatever reason, to cut my stay short and head back upstairs (I was probably eager to watch cartoons or continue drawing more of my own personally created Mega Man Robot Masters), but still I'd seen enough to know that Doom was a game that I definitely needed to try out for myself when James wasn't there.

I got that opportunity the next day, when James and his friends were out raiding the local comic-book shops and doing whatever else they did with their free time. As soon as I got home from school, I hurried downstairs, turned off all of the lights (which seemed to be the appropriate thing to do), and began my first personal session with Doom!

Here's what I remember about that first session:

Episode 1, Mission 1

I hadn't actually seen this stage, because when I started watching James play the game, he was pretty deep into its first episode. The mission that he was playing at the time had environments that were darkly lit, cramped in nature, and rather mechanical-looking, so I didn't know what to expect from the opening stages. "Are they similar visually and design-wise?" I wondered. "Or do they say something different about the game's world?"

So obviously I had no real sense of the game's setting.

Well, that changed within seconds when I loaded up Episode 1's first mission and promptly experienced what I consider to be the moment: When the mission started, I immediately headed left and ran up the stairs, and upon doing so, I immediately stopped in my tracks and entered into a state of awe.

Beyond the three windows in front of me lied one of the most jaw-droppingly impressive visuals I'd ever seen in a video game. It was a stunningly rendered, breathtaking mountainscape, and it stretched across and wrapped around the entire complex. As I moved back and forth and observed it from different angles, its silently threatening assemblage of towering gray and black rock formations followed my every movement and did so as if they were playing the role of an oppressive gatekeeper.

And the mountains' portentous presence alone told me the whole story of the location in which Doom's action was taking place and the gravity of its protagonist's plight.

I stared intently at those mountains for a good three minutes or so, and in that time, I marveled at the captivating atmosphere that they were creating and soaked in as much of it as I could. Also, I fervently examined their every realistic-looking texture and pixel and imagined how awe-inspiring and spine-tingling such formations would look if I was able to see them in person.

"Where did this game really come from?" I wondered as I entrancedly gazed at the mountains.

These opening screens, and indeed the entirety of the opening stage, rate as high as any other on my list of iconic starting areas. The mountainscape visual's making such a powerful impression is a big reason why that's true, yes, but there were also a few other indelible moments.

There was, for instance, my first encounter with the imp that was hanging around the stage's third room. It was positioned on an elevated platform in the far north, and I exchanged fire with it from a distance. It was an intense encounter, and I remember frantically dodging its fireballs and trying to find openings to return fire. (Admittedly, though, I could barely identify the creature that was throwing the fireballs because it was so pixelated. I didn't get a good look at an imp until I entered the stage's final room, which contained one of them.)

Then there was the stage's musical theme, which, in contrast to what I heard a day earlier, was an absolutely rockin', adrenaline-raising piece. It invigorated me in the most powerful way possible, and its ability to do so helped it to become another instantly iconic element of Doom.

Though, I did realize at some point that the theme's high-spiritedness was mostly a veneer. When I listened to the piece more closely, I was able to observe that it was actually urgent in tone, and it was designed to spur me into pushing forward with fear as my driving force. It wanted to make me feel unsafe and under attack even when there were no apparent dangers in sight. "Keep moving, kid, or something's going to come along and get you!" it continued to tell me.

And, also, the theme was outstanding in quality. It had powerfully resonant instrumentation and note strings that were so richly complex that they were almost hypnotizing (and "unmistakably Doom," as I'd come to term them). And for those reasons, it was one of the best video-game tunes I'd ever heard!

And by the time I finished the first mission, I could say with confidence that I'd never played a game that looked or sounded like Doom or exuded the same type of vibe.

"This game is something special," I thought to myself.

Episode 1, Mission 2

In this stage, the music suddenly turned eerie. Its bass' deep reverberance was more haunting than before, and its prolonged notes were dripping with foreboding energy. And as I listened to it, I became filled with apprehension.

Resultantly I was hesitant to move from the stage's starting point even though the place was quiet and there was seemingly no activity occurring. I didn't trust what I was seeing because the stage's tune was clearly telling me not to.

The first thing that I learned was how big a mistake it was to heedlessly charge out into the open in a Doom game. My doing so had the unintended effect of alerting every enemy within the immediate area to my presence. And of course I got destroyed in seconds.

In my successive attempts, I took a different approach: I slowly sneaked around corners and picked off enemies one at a time. Though, I'd usually freak out and abandon that strategy the moment an enemy would spot me from afar and fire at me from a location that I couldn't pinpoint. Then I'd panic and run around in circles and hope to spot the enemy before it could kill me.

So my experience in Mission 2 was mostly a learning process. It was all about figuring out how to use the environment as cover and getting a sense of how spatiality worked in a 3D space.

The tune's tempo picked up a bit after its intro finished playing, and at that point, its eerie tones gave way to an investigative-sounding, caution-inducing moderato that worked to evoke feelings of vigilance and permeate the stage with a persistent air of mystery. The piece's message eventually became clear to me: "Make sure to take your time and look around," it said, "and be prepared to find danger lurking around every corner."

And as I inched my way through the rest of the stage in paranoid fashion, I came to understand that Doom's composers were masters of their craft. They knew exactly how to toy with your emotions and inspire you to immerse yourself in the action in many different ways.

The basement, itself, also played an important role in my experience: Its entire center was enveloped by an uncomfortable darkness, and its outer edges were textured only by the eerily faint sunlight that was emanating from the barred windows in the area behind me. The resulting atmosphere worked to heighten the tension that I was feeling as I played through stages.

Episode 1, Mission 3

In this stage, both the music and the atmosphere became darker in tone and even more disquieting, and as I drank them in, I felt as though things were about to get really serious in this place.

The biggest problem was that I was short on ammo. Because, apparently, I hadn't been as thorough in my exploration as I thought. So my only option was to stick with my newly developed strategy of hiding in unoccupied rooms and luring and funneling enemies into them. Doing so allowed me to deal with them up close from a favorable position and thus make it easer to avoid wasting bullets.

What I learned in this stage was that Doom was loaded with secret rooms I could access by pushing up against conspicuous-looking walls and mashing away at the action button. "Simple enough mechanic," I thought.

But then there was also a cryptic method of accessing secret rooms: opening sliding walls by making contact with invisible timed-based sensory triggers, which were usually placed far away from the walls that they opened up. What I discovered here was that you had to race around the nearby area to find the walls in question and listen closely for aural cues (the closer you were to a slide-open wall, the more likely you were to hear it opening and closing).

One such secret room awarded me with a health-boosting Soul Sphere, but honestly, I found that room by luck. I didn't figure out how I was triggering its associated slide-open wall until my second session with the game. It wasn't until then, also, that I discovered that you could run by holding down the B button.

The more I played the game, the more I learned about the level designers' tendencies. I became aware, for instance, of their favorite trick: They loved to place an important item in the middle of a wide-open space and make it a trigger. And the moment I'd obtain it, all of the nearby walls would instantly open up and reveal hordes of monsters that had been waiting for the chance to ambush me. And if I wasn't prepared to react (and sometimes I wasn't), I'd be quickly overwhelmed and killed.

And let me tell you: To enter a large rectangular room with a key card in its center portion was to know the meaning of fear. You knew what was going to happen the moment you touched that key.

As James would often comment right before obtaining a conspicuously placed item: "Let me guess: Every goddamned wall is going to open up, and a thousand enemies are going to appear out of nowhere."

And that was usually what would happen!

The Unceremonious Ending

From that point onward, my time with Doom was mostly dedicated to learning about the game's intricacies: how the enemies behaved, which weapons were most effective against certain monsters, how to skillfully strafe around corners and use the surrounding environment to my advantage, and how to identify when an enemy onslaught was likely to occur.

Though, I wasn't able to get very far into Doom and really put my newfound skills to the test because I suddenly ran out of time when the basement's side door opened and James returned home. Because as soon as he walked in, he threw me out!

But that was OK because Doom didn't need any more time to convince me of its power. It already had me firmly in its grasp.

I was hooked on its action, and I couldn't wait to get my SNES back so that I could hook it up to the TV in room and begin exploring the game more thoroughly!

I had to wait four or five days to get the chance to do so. I spent the intervening period digesting what I'd seen and obsessing over the game's technology, which still seemed amazing to me.

I couldn't stop thinking about all of its impressive effects: how objects scaled and their textures and details became increasingly discernable the closer I got to them; how lights flickered; how brightly lit corridors spilled into those that were shrouded in darkness; how any structure, no matter how large or small it was, could move or shift in any direction; how some rooms would suddenly transform around me, their walls lifting up, their passages shuttering, and their platforms lowering in concert to reveal the presence unseen dangers; and how each accompanying sound sample, be it a rifle's discharge or a projectile collision, had great punch to it--a viscerally pleasing impact that gave very real weight to the action that was occurring onscreen.

Doom even had a cool top-down automap that could be zoomed and rotated! And, incredibly, you could continue playing the game while you were viewing it from that perspective!

It was all so mind-blowing.

We were still in the 16-bit era, but after seeing what Doom in action, I felt as though I was somehow witnessing the birth of a new generation of video games and getting a taste of it without having to buy a whole new machine!

"How is

SNES capable of doing any of this?" I continued to wonder.

The only specific instance that I remember from my second session with Doom and my full play-through of Episode 1 was my first encounter with the barons of Hell--a mean- and nasty-looking pair of minotaurs who seemed to be invincible (because, I think, I didn't have a rocket launcher at the time). So the only strategy that I could come up with was to run away from them and hope that taking them down wasn't a requirement.

But eventually I learned how to deal with them. I discovered, via experimentation, that they weren't actually invincible (they were just really tough) and could be taken down with any weapon if you had a large enough supply of ammo.

That knowledge alone, though, didn't make them any easier to defeat, and it took me a long time to become proficient at cleanly taking down even a single baron.

And in the end, I was happy to say that Doom was now one of my new favorite video games. I was highly enamored with virtually every aspect of it: how it looked, how it sounded, how it played, and how it used its technology to present its world and its action in a mind-blowingly new way.

I loved, in particular, its setting and the role in which it placed me: I was an average grunt who found himself all alone on a moon base with no point of contact, and I was left to my own devices to navigate my way through a mysterious, elaborately designed military compound that was infest with hell-spawned demons.

"What a fantastic idea for a story!" I thought.

But the most interesting part was that Doom's were actually silently looming threats. The enemies weren't running stomping around everywhere and roaring loudly as they actively hunted me, no. Rather, they were hiding in the shadows, and sometimes I couldn't easily locate the spaces from which their snortling was emanating.

I knew that they were there, somewhere, but I could never be sure about their exact location. They could have been hiding in the pools of shadow that formed the reactor room's outer edges; behind the solid-looking wall on the room's left side; or right there in front of me, their presence obscured by a similarly colored (and equally pixelated) surface-texture. And I'd continue to feel unsettled even after getting an idea of where they were because I wasn't wasn't sure how many of them would pop out when I finally moved to their location!

That was because Doom created an amazingly tense, incredibly immersive atmosphere with its sprawling, untamed level design and stages that were filled with concealed ambush points and darkened, shadowy branches; with its unease-inducing spatial audio; and with its extremely ominous and foreboding music. As I slowly inched my way through its spaces, I was filled with feelings of tension and anxiety, and I was never sure if the next room would be unoccupied or contain a demon that was waiting to tear me to pieces.

I could see everything, yet, really, I could see nothing.

And that psychological aspect of the experience played a huge role in making Doom's action feel so exceptionally captivating and exhilarating. No other game had ever played with my mind in that way or managed to make me feel uneasy and thrilled at the same time.

What Doom did with its setting was remarkably novel and awe-inspiring. I was deeply entranced by all of it.

Doom often threw me into chaotic, hectic battles and tasked me with enduring situations in which I was being attacked by hordes of monsters, but still its action was never strictly about survival, no. In most cases, it gave me everything that I needed to capably overcome the odds. It provided me access to all kinds of destructive armament that I could use to effectively mow down the forces of Hell.

And it was how I approached the action that determined how well I'd do. If, as I learned painfully, I simply ran out into the open and frantically fired away at anything that moved, I'd pay a hefty price for doing so; I'd quickly deplete all of my ammo and take a beating. But if I employed a more calculated run-and-gun strategy and attacked only when the odds were in my favor and when I could funnel enemies in and draw them into close-quarters combat, I'd have a greater chance of succeeding (I just had to be careful not to spaz out and fire my rocket launcher at close range, which I was apt to do).

The designers obviously intended for me to take the latter approach. They provided merely an adequate amount of ammo and thus promoted tactical action over reckless play. And if I stupidly engaged in the latter, I'd be promptly cut down by a large group of imps or I'd run out of ammo and be left with only my firsts or my largely useless chainsaw (to which only the pink demons seemed susceptible).

That was the great thing about Doom: It wasn't about mindless action (as some of its media detractors would insist), no. It was multifaceted. It had strategic gameplay, great level design, a strong exploration factor, interesting puzzles (most of which were centered around the obtention of access-granting key cards), and even a few platforming challenges. Its labyrinthine compounds contained secrets galore, and part of the fun was re-exploring a stage after clearing away all of the enemies and interacting with every wall and every object in search of cool secret areas.

Doom had everything you could want in a 3D action game.

I loved Episode 1 so much that I played through it multiple times in the months that followed. Its opening mission, as I said before, was iconic to me, and I considered it to be one of the greatest "first stages" in gaming history. And I held all of its other missions in high regard, too. I felt as though they were just as quintessential as the opening mission.

I never got tired of those 8 missions. Even after playing through them a dozen times, I continued to derive great enjoyment from traversing them, exploring them, observing them, and soaking in their atmosphere.

They were fun in every way.

I'd usually play on the default middle difficulty, "Hurt Me Plenty," but on days when I was feeling frisky, I'd bravely dabble in the "Ultra-Violence" and "Nightmare" modes. I preferred doing that over playing through the game's second and third episodes, whose missions were, I thought, too long and complex and largely bereft of the first episode's all-important unease-inducing claustrophobic element.

Whenever I played in those modes, I'd always feel as though I was under-equipped, and I'd struggle to deal with all of the enemies that were being thrown at me. I'd have far less fun.

I remember playing through those modes once apiece and feeling underwhelmed each time. So it seems appropriate that my only outstanding memory of those experiences is my "battle" with the Episode 2 end boss: the Cyberdemon.

The alleged showdown is memorable to me not because it was a tense, epic clash that was filled with exciting, dramatic exchanges but because I didn't even know that a boss encounter was occurring. After I exited the stage's central portion, I saw a small collection of indiscernible pixels in the distance, and then I stood there and furiously fired rockets at it until it died. And because I never got a clean look at the boss, I had no idea what I'd just destroyed.

What happened, apparently, was that the boss had gotten stuck on a pillar and thus lost its ability to function. So I was able to freely assail it from a long distance.

The boss in question had to have been the "Cyberdemon," I figured, because it was the only manual-listed foe that I hadn't yet encountered and it was otherwise too resilient to be a baron, an imp, or a demon.

I was, however, able to get a good look at the Episode 3 end boss: the grotesque Spider Mastermind. But I immediately ran away from it and employed the same strategy of attacking from as far away as possible. I did so with the BFG, whose great striking power helped me to win the battle quickly.

I mean, sure: I knew that I was cheating myself out of an exciting, satisfying battle by employing such a cheap tactic, but by that point, I didn't care anymore. All I wanted to do was get the battle over with so that I could say that I'd completed all three of Doom's episodes.

But there was one aspect of the second and third episodes that I did really enjoy: the music. I thought it was just as outstanding as Episode 1's. It did an equally great job of creating a tense atmosphere and evoking feelings of unease.

I liked, in particular, the Episode 2, Mission 1 theme (Hell Keep, as it's called). It was a hypnotically rhythmic, appropriately-evil-sounding piece that was perfectly matched to the stage that it accompanied: the aggressively guarded Gates of Hell. It had the unique power to fill me with fear but at the same time infuse me with the energy and the spirit that I needed to stay in motion and bravely face down the hordes of pursuing monsters. It served as an important motivational force in moments when I desperately needed a boost--when I was lost, really short on ammo, and feeling overwhelmed by the odds.

I liked this tune so much that I made sure to include it in my video-game soundtrack collection (I recorded it with the same aging tape recorder that I received as a gift from my aunt in the mid-80s). I listened to it quite often, and usually I used it as accompaniment to my daydreams and particularly those in which I imagined myself as a commando-style soldier taking on the forces of evil!

I recorded the entirety of Doom's soundtrack, in fact, and I derived a similar amount of inspiration and enjoyment from pretty much every one of its tunes.

Because Doom's music was some of the best video-game music ever composed, and it deserved to be given special treatment and appreciated in as many ways as possible.

And even though I wasn't fond of every aspect of Doom, I still regarded it as close to perfect. I considered it to be the one of the most wonderfully unique, fully realized video games I'd ever played. It was, I felt, a masterpiece of game design, and I derived great enjoyment from it for years in following and up until the SNES' final days.

But the story didn't end there, of course. It was just getting started! My experiences with SNES Doom represented only the first chapter.

The next part of the story began in 1998, when, basically out of nowhere, James excitedly ushered me down to the basement and introduced me to his newest purchase: his new computer--a "Microsoft Windows" PC!

This newfangled computer was like none that I'd ever seen before. It had a colorful desktop that barely resembled the drably designed, text-heavy screen displays that I remembered seeing in my early years as a computer gamer. This desktop, in contrast, was populated with animated imagery, interactive icons, and a slew of other intriguing-looking objects. And I was astonished by all of it!

It was right at that moment that my perception of the computer scene was completely shattered. It hadn't died out, as I thought. Rather, it was still going strong. And it had evolved significantly since the early 90s. All while I wasn't looking.

And over the course of a few days, James taught me all about the basics of the Windows operating system, and he showed me how to browse this new thing called "the Internet" (though, admittedly, I wasn't clear on the different between "the Internet" and a "browser," and I thought that they were interchangeable terms).

And better yet, he agreed to let me use his computer during the night hours while he was sleeping!

No comments:

Post a Comment