How an ambitious few bravely shattered conventions and put together one of the grandest, most transformative games I'd ever played.

Frankly, it was starting to get on my nerves: Every time I'd run a Castlevania-related web search, its name would dominate the results listing. Every time I'd hit up Yahoo! and attempt to research a particular aspect of a recently played series game like Castlevania: Bloodlines or Castlevania Legends, the same ol' name would come to occupy the first two or three pages' worth of returned links and completely crowd out whatever it was that I actually typed.

"What is it with this damn 'Castlevania: Symphony of the Night?'" I'd wonder for the umpteenth time as I skimmed through the ever-familiar search results. "Why do these search engines insist on spitting it out as the most relevant match when clearly my search queries couldn't be any more disparate?! It's so annoying!"

That's how it was during the early days of my Castlevania site's construction, when I was busily journeying my way through history but kept finding myself distracted by the uncomfortable reminder that a highly acclaimed series entry had recently seen release on a modern console that I knew little about and didn't care to research.

I realized that this was going to be a huge problem for me going forward, but I couldn't do anything about it. I simply didn't have the motivation to act. Because at the time, I had no desire to own a second next-generation console, and I knew that I'd be unlikely to find an alternate way to gain access to the game.

And with things being as hectic as they were (extensively covering a 12-game series was nonstop work), I just didn't need the headache that came along with thinking of ways to deal with the issue. So what I decided to do, ultimately, was simply ignore the topic of Symphony of the Night for as long as I could. "Let that game wait until I'm good and ready to acknowledge its existence!" I said with a sneer.

For however much I rationalized that I was annoyed with the game only because its unavailability was threatening to stunt my site's growth, I knew that my negative sentiments were actually coming from a place of bitterness. After all: Here we had yet another instance of Konami bringing a Castlevania game exclusively to a non-Nintendo system after previously failing with that strategy. "Why not also bring it to the N64?" I wondered with a feeling of frustration that was similar to the one that overcame me when I first saw that only-on-Genesis Bloodlines commercial five years earlier. "You know: The place where the audience who grew up with the series and actually appreciates it is currently playing?"

At the time, I was only vaguely familiar with Sony's 32-bit PlayStation, yet I knew enough to be in a place in which the mere mention of its name would fill me with feelings of resentment. Because, you see, my opinion of the PlayStation brand was informed mainly by the obnoxious, needlessly inflammatory commercials that the company was pumping out a rapid pace. The biggest offender was the one in which a man wearing a Crash Bandicoot costume drove up to Nintendo's headquarters and started shouting disparaging remarks through a megaphone.

"Why is Sony choosing to be so petty?" I'd wonder each time that commercial aired. "Why does this company think that it can win me over by tearing down the competition?"

I'd always found the idea of system wars to be repellent, so this marketing tactic was grounds for me to write off the PlayStation entirely. Because no company was going to endear itself to me by pissing all over an industry pioneer--be it Atari, Nintendo, or whatever--and telling me that there was something wrong with me for liking its games. I regarded this type of marketing as egregious, just as I did in the early 90s when Sega was using a similar marketing strategy, and there was no way that I was going to reward such behavior!

Castlevania: Symphony of the Night's only crime, then, was guilt by association.

I was, of course, acutely aware of how childishly I was acting. For however pissed I was about the whole exclusivity deal, I possessed enough wisdom to know that I had nothing to gain from ignoring great games and successful consoles because I felt somehow aggrieved by their creators. So I knew that if I wanted to play Symphony of the Night, which was by all accounts "the best Castlevania ever," and earnestly provide coverage for it on my site, I was going to have to stop being silly and get myself a PlayStation.

And because it just so happened that there were a few other PlayStation games that I was interested in playing, it felt like the perfect time for me to jump in. So right around then, in the autumn months of 1999, my brother, James, and I went to our local Electronics Boutique and picked ourselves up a PlayStation and a copy of Castlevania: Symphony of the Night.

Though I'd chosen the path of reasonability, I couldn't deny that I was feeling like a bit of a traitor for bringing a PlayStation into my home. I mean, here I was unboxing a console whose marketing campaigns entailed belittling enthusiasts like me who had a strong attachment to the medium's history and its most notable contributors. It was like I was fraternizing with an enemy that represented everything that I deplored about the video-game industry.

But a few minutes later, something entirely unexpected happened: All of my lingering feelings of resentment vanished in an instant as I placed the PlayStation atop our den's makeshift "game cabinet" (the shoddily constructed assemblage of cheap wooden trays that lied in front of our big-screen TV) and suddenly realized what this console symbolized. Even back then, before my passion for the medium was fully developed, I always felt a sense of enrichment when I came to own a new type of console--when I gained access to an unknown, unexplored platform whose library was likely filled with the types of wonderfully unique games that I'd love if I took the time to discover and play them.

So suddenly I was excited to think about what this new console--my new Sony PlayStation--represented!

But more immediately, there was really only one question that needed to be answered. It wasn't "Is Symphony of the Night, on its own, worth the price of admission?", no, but rather "How in the hell do we get this game CD to fit into the disk tray?!"

No, seriously: James and I spent upwards of twenty minutes trying to figure out why the console's lid wouldn't close after we placed the CD onto its disk tray's central spindle. "Is the console defective?" we wondered. "Or is it that we're supposed to remove part of this apparatus and the screw it back over the CD?"

We didn't attempt to depress the CD onto the spindle because we felt as though the CD might snap in half if we pushed down on its sides with any amount of force. What we did, instead, was just kinda lay the CD down atop the spindle and leave it tilting at an angle. And that obviously didn't work.

In the end, we had to admit defeat and call Sony's customer-service department to find out the correct method for inserting CDs into the PlayStation.

The company's operators must've thought we were a couple of crackpots.

And that was about as far as James' interest stretched. As soon as the PlayStation finished booting up, he left, and he didn't come into contact with the console again until months later, when, in continuing the long tradition, he started amassing a large collection of used PlayStation games and of course never played any of them for longer than an hour. That was James: the flakiest of flakes.

So now, all that remained was my date with destiny.

I was eager to play Symphony of the Night, though my excitement was somewhat tempered by a feeling of skepticism. After all: There had been plenty of instances in which I'd been misled by Internet opinion. There were times when I'd purchased an allegedly "amazing" game only to discover that those who deemed it such did so on the basis of their favorable assessment of game aspects that held little value to me (graphical "realism," high level of violence, multiple layers of complexity, campaign length, and such).

So I had reason to suspect that Symphony's values might align more with those from, say, Mortal Kombat, which was showy and eventful but ultimately shallow, than with those from Street Fighter II, which was mechanically brilliant, incredibly deep, and rich with substance.

I mean, I had to take into account that the PlayStation was supposedly the console for cool, "mature" people who championed games like the former. These were the types who didn't care to find common ground with some "unevolved" pleb like me with my "broad range of interests" and "20-year history with the medium." According to them, I wasn't a "real gamer."

So I didn't know if I could trust what PlayStation fans had said about Symphony of the Night.

But as I soon learned, Symphony of the Night was above all of that nonsense. It didn't care to dignify my skepticism or preconceived notions, and it had no interest in giving credibility to stupid things like system wars or console tribalism, no. Rather, its was a tale of transcendence and grand ambition.

Right from the jump, it showed itself to be uncompromising in its effort to blow me away and exhibit majesty for me in a way that I couldn't possibly have foreseen. It wasted no time in expressing its intense desire to epically exceed my expectations. And it started that endeavor by hitting me with an unanticipated, awesome opening action scene that brilliantly provided context for its story by reenacting the final moments of Dracula X: Chi no Rondo (or "Rondo of Blood," as we called it) its direct predecessor.

"How did I not know anything about this element of the game?!" I wondered in amazement.

I'd missed out on the PC Engine-exclusive Rondo of Blood (at that point, my exposure to Dracula X was limited to what I'd seen in the butchered SNES conversion), so it was surreal to me to unexpectedly find myself in control of Richter Belmont in the traditionally designed side-scrolling "Final Stage" of a game I'd never played. Until then, my only knowledge of this scene was derived from Rondo of Blood screenshots that I'd viewed on the Castlevania Dungeon.

And now here I was suddenly playing it (or at least an interpretation of it)!

"What an awesome surprise!" I was inspired to think.

As I ran about the structurally faithful Castle Keep and collected hearts while drinking in scene's absolutely rocking musical accompaniment, I was struck by how much this "Final Stage" reminded me of the early minutes of Super Metroid, whose creators (R&D1) effectively used the familiar setting of old Brinstar to evoke the spirit of the series' progenitor and make me feel instantly at home. This "Final Stage," too, was able to create an immediate sense of comfort and a feeling of authenticity that did so much to convince me of its creators' competence.

It had to have been, I thought, that Symphony's creators were keenly aware of Super Metroid's creative successes and wished for their game to capture its spirit, though to what extent I wasn't yet sure.

But one thing was crystal clear to me: The people who made Symphony of the Night were highly respectful of the games that influenced it. So I felt safe in trusting them. And I was certain that the game they'd create was about to take me to a very special place.

I mean, sure: I felt inclined to criticize the voice acting (in both this scene and every scene in the entire game) for its hammy nature and how it was memorable for the wrong reasons, but I wasn't at all offended by its presence. To the contrary: I considered it to be an essential part of the experience. For however goofy the dialogue was, it worked to provide the game an extra bit of character that would have been lost had each scene instead been accompanied by cold, awkward silence.

Had I never played the game again, I wouldn't have ever forgotten memorable lines like "What is a man?" and "Have at you!" So I could say, even early on, that Symphony of the Night was actually one of the most utterly quotable games around!

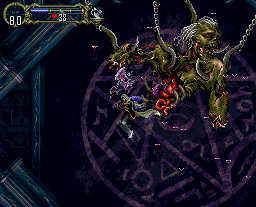

Alucard's campaign felt epic from the start. Each of its events bled into the next and contributed a big puff to the ballooning sense of enormity.

I remember it all so vividly: Alucard raced through the haunted woodland--the sounds of fierce winds and crashing thunder providing the scene an entrancingly eerie texture--and cleared the closing drawbridge with a breathtaking leap. The tension built as he slayed the guardian Wargs within the dark, silent Castle Halls, which were supplied the briefest of luminance by the frequent lightning strikes. Then, suddenly, the castle sprung to life, much like old Brinstar and Crateria did in Super Metroid, and another incredibly rousing tune (which I'd later come to know as "Dracula's Castle") began to play.

Palpable ambition reverberated through every corridor that followed. Even those that were devoid of enemies or purely transitory were imbued with a haunting quality that contributed greatly to the overarching sense of grandeur.

I wasn't expecting any of this: the impressively crafted cinematics! The smooth-as-silk controls! The amazing graphics, animation, and visual effects! The unfathomably awesome music and sound design! The deeply enchanting atmosphere!

"Where did this game come from?" I'd wonder every few moments as the game continued in its endeavor to constantly find new ways to fill me with awe.

I wasn't a fan of RPG systems in side-scrolling action games, but Symphony's was implemented so incredibly well that I never once felt intimidated or encumbered by it. And it was unmatched in terms of how it visually communicated information: registered strikes would display numbers that sometimes wiggled, pulsated or zipped off the screen with a neat distortion effect.

Even the leveling-up effect had serious punch to it: When Alucard gained a level, he'd glow intensely and dynamically, and a celestial-sounding, arpeggio-style chime would play. I couldn't name another RPG or RPG-style game in which the act of leveling up held so much visceral appeal!

I was utterly engrossed in Symphony of the Night. I was constantly looking forward to seeing what each new room held--to gauging its visual wonder and finding out which gorgeously designed enemies were lurking within it.

I couldn't wait to find out what the game was going to hit me with next!

Still, though, there were many moments in which I took the time to idle within vacant rooms for a while and let myself be enveloped by their atmosphere. I made sure to soak in their every conveyance--the feelings of danger, unease and epicness that were being generated by their appropriately symphonic combinations of amazingly detailed backgrounds (one of which had a giant eyeball tracking my progress from the Marble Gallery's exterior) and sweeping, orchestral-level musical compositions.

This game knew how to stir my imagination and fill me with energy, and for that reason, I was always pumped to see and hear more of it!

Because I'd done a minimal amount of research on Symphony of the Night in the run-up to purchasing it (which was a normal practice for me, as I preferred to be completely surprised by games' content), I came to hold many assumptions about the game. I expected, for instance, that the majority of its boss cast would be comprised of newcomers and that the remainder of the list would be filled out by a handful of overexposed veterans (like the Phantom Bat, Medusa, Frankenstein's Monster, the Grim Reaper).

That's why I was genuinely shocked when I ran into Slogra and Gaibon in the Alchemy Lab! I couldn't believe it: Two iconic bosses from Super Castlevania IV, one of my all-time series favorites, were teaming up in a game that I never imagined would welcome their kind! Because, really, they were a pair of one-off bosses from a game that recent Castlevania directors seemed apt to ignore. They basically treated as non-canon characters.

Yet here they were in Symphony of the Night, looking as though they'd been ripped directly from their game of origin. Save for their having a few newly introduced tag-team maneuvers, they looked and performed just like I remembered. And I couldn't have been more pleased by that!

I was simply thrilled to see them again!

I mean, so what if they'd been demoted to jobber status? That didn't bother me at all. Because their very appearance was a special-enough event. It represented another one of those unexpectedly awesome moments that made the game for me!

And I was excited about the message that their appearance sent: It told me that Symphony of the Night had no intention of disregarding the contributions made by the games that predated Rondo of Blood. It told me that this game was going to be all-encompassing in a very special way.

"In this game, anything is possible," it said to me.

And I couldn't wait to find out who was going to show up next!

From there, though, my memories become less specific. They become more of a series of small recollections and memory fragments that speak of a memorably epic experience. Honestly, I'd be here for two or three years if I attempted to talk about every moment and every detail that meant something to me, and the result of that effort wouldn't be particularly healthy for your browser.

So instead I'll speak of the rest of my experience in more general terms.

Much like Mega Man X and Super Metroid before it, Symphony of the Night was, in its opening hour, looking to be one of those games that seemed capable of achieving a perfect score in just about every conceivable category. The sheer awe-inspiring quality of each newly introduced setting, music track, boss battle and game mechanic was further testament to how astonishingly ambitious the game was.

As I continued playing it, the same questions kept popping up in my head: "Did the developers know that theirs was turning out to be one of the most amazing games ever made? And if so, then when did they realize it?" "Who designed all of these unique environments, textures and backgrounds, all of which are painstakingly filled to the brim with character-imbuing details? Who could be that inspired?" "And who composed this godly, incredibly powerful soundtrack, whose every diverse, masterfully composed piece is a lesson in how to use music to all at once build atmosphere, invigorate the player, and tell a climactic story? And was he or she possessed at the time of its creation?"

During my first play-through, I never would have guessed that Symphony of the Night was a budget title. Because its outstanding quality belied such a notion. And had I been asked how much I thought it cost to make, I would have confidently stated, "This game, from what I can see, is nothing short of an amply funded large-scale production!"

I mean, how could it have been anything less when it was dripping with so much ambition? When clearly its creators have gone the extra mile in every area? It had more than a dozen expansive areas to explore, a soundtrack that was comprised of a multitude of impassionedly composed tunes, hundreds of uniquely attributed weapons and items, twenty-plus spectacularly presented boss battles, a large number of cool spells, and an absolutely enormous bestiary that was filled with a diverse assortment of superbly designed baddies!

We're talkin' about three types of mermen, man! The other games never thought to give you more than one!

This game had an exhaustive amount of content, and all of it was great.

I didn't even mind that the designers recycled some enemy sprites from Super Castlevania IV, Rondo of Blood and the Sharp X68000 version of Akumajou Dracula. Recycled enemies represented what--a quarter of the list? Big deal! That was only 28 (or so) of 114! There were enough new enemies here to populate two or three separate games!

And the best part was that you didn't need to collect everything or even know about, say, 75% of the game's content to have an amazing experience with it. A great many of its weapons, items and spells were purely optional. You didn't have to find them or put them to use unless you desired to.

The best action-adventure games were recognized as such because they brilliant in how they invited players to explore and interact with their environments, but Symphony of the Night took it to next level by allowing you to do so not just with its environments but also with its every system and mechanic. It would even let you change the color of Alucard's cape!

That's how much power it was willing to trust you with.

There was always more to Symphony of the Night than I realized. When I defeated Richter Belmont, for instance, I was sure that I'd earned ultimate victory and that the game was over. As the credits rolled, I reflected upon how I'd just completed one of the most outstanding Castlevania games in existence. I felt that the ending sequence was anticlimactic, sure, but still I got six-eight hours of high-quality entertainment for the $30 I'd spent. I couldn't have asked for anything more.

At that point, I was sure that I'd seen everything that the game had to offer.

But I hadn't: When I went online and started reading more about the game, I discovered that there was a whole other half to it! I learned that if I completed a few undemanding tasks and won the final battle under certain conditions, I'd get to extend my quest and explore an upside-down version of the castle!

"That's nuts!" I thought to myself in an astonished manner. "There's another half to a game that I already consider to be, in its currently recognized form, one of the best I've ever played?!"

So I immediately returned to the game and started the process of unlocking its second half.

And I loved the second half of the game just as much as the first! The upside-down castle was, I felt, a simple idea that was executed brilliantly. The designers didn't simply invert the existing castle and call it a day, no. Rather, they carefully and thoughtfully considered the logistics of the newly contoured environments and insofar implemented workable schemes for enemy-placement and platforming.

Also, they were zealous enough to populate the upside-down castle with dozens of uniquely encountered minor enemies and provide the player eleven additional bosses! So what had the potential to be mere padding turned out to be a marvelously designed expansion that could have stood alone as its own game!

Somehow Symphony of the Night blew away the N64 games on what was likely only a 10th of their budget. It managed to find success despite Konami's best efforts to slot it as a second-tier release. In its first run, it achieved sales of somewhere around 800,000. And I think we'd all agree that it deserved to sell much more than that!

So when it was all over--when the stirring credits theme, I Am the Wind, had finally drawn to a close--all I could think was "What a grand experience!" I knew that I'd just completed one of the medium's most supreme offerings.

I was so utterly enamored with Symphony of the Night that I couldn't help but immediately play through it again and then a third time in Richter Mode, which, I was happy to discover, was made to accommodate a wonderful mix of new and classic gameplay styles. I felt that Richter Mode represented some of the best post-game content ever. Its inclusion served as another example of how astonishingly deep Symphony of the Night was.

And in the end, I could say that Castlevania: Symphony of the Night was worth every single penny of the $200 that I spent for both it and its host console, the Sony PlayStation. And I was certain that I'd be extracting great value from both of them for years to come.

Symphony of the Night's successes were many, and there was one in particular that really meant a lot to me: Its succeeding in being all-encompassing, as I hoped it would be.

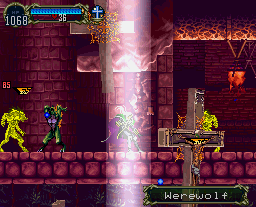

If you look carefully, you'll find that it respectfully pays tribute to just about every other game in the series: It replicates some of Castlevania's most memorable environments (the main halls, the castle keep, etc.). Aside from borrowing Simon's Quest's gameplay formula, it also reuses one of its quest elements: At a certain point, it tasks you with collecting the scattered body parts of Dracula! It makes obvious references to Dracula's Curse (Alucard, himself, is one of them) and features zombified versions of its heroes: Trevor Belmont, Grant Danasty, and Sypha Belnades, the three of which form a deadly boss trio. Its bestiary includes enemies whose sprites were ripped directly from Super Castlevania IV (Slogra, Gaibon, Dhuron and Thornweed); also, Richter can brandish the whip in the same way that Simon could. And much of its design is informed by Rondo of Blood, from which it borrows a slew of enemies and entire environments (like the clock tower with its collapsing bridge and trio of vertical passages, all of which are faithfully recreated).

Also, it addresses the castle's changing appearance from game to game by explaining that Castlevania is an ever-morphing "creature of chaos," which is, I feel, a genius characterization. I've been in love with the term since the first time I heard it.

And I appreciate everything that it does to tie together all of the series' disparate elements and cover for its inconsistencies.

After I completed Symphony of the Night, I couldn't wait to start covering it on my site. More than anything, I dreamed of providing pixel-perfect captures of the game's enemies, whose collective, to me, represented the Holy Grail of sprite-rip targets. I just didn't know how I was going to do it. Because at the time, an obvious method of ripping sprites from PlayStation games didn't seem to exist.

I found an answer, though, when I learned about the PlayStation emulator Bleem!, which was capable of running actual game CDs! I immediately downloaded and installed it, and then I spent the next few days excitedly tapping away at my keyboard's Print Screen button and snapping screenshots and ripping enemy sprites directly from the Master Librarian's bestiary list (though, because I'm obsessed with displaying enemies in their full glory, I inevitably went back in and painstakingly captured non-cropped versions of the larger enemies).

And I was quite proud to be the first Castlevania webmaster to have Symphony of the Night's entire enemy cast on display!

And Symphony of the Night's mere presence on my site was enough to greatly enhance its value. It imbued the site with an increased sense of life. It significantly enriched it.

I saw the addition of Symphony of the Night content as a turning point for the site, which before then was, well, kinda lame. But suddenly it was now worth visiting!

Such was the allure of the Symphony of the Night, whose radiance served to attract series fans both old and new.

Symphony of the Night is another example of what I call a "peak game," which by definition is any series entry that so masterfully perfects the formula that you can't surpass it with a sequel that simply increases the size of the world and the complexity of the systems. I bring this up because I'm always coming across forum posts filled with people who crave a "Symphony of the Night 2" and believe that its creators would somehow be able to top the original. If I were to respond to such people, I'd tell them to take a closer look at the GBA and DS Castlevania games, which clearly demonstrate that you can't create a better Symphony of the Night merely by reusing its formula and adding in more stuff.

Really, those who so desire for Castlevania to retake its place in gaming's upper echelon should know that traveling this road is pointless. It results in only more of the same and strings of underwhelming sequels. If Konami's brightest want to produce a game that has the power to rock our worlds, as Symphony once did, they'll have to find the courage to take risks and move in a new direction. They'll have to possess the mettle necessary to turn a deaf ear when logic and history suddenly creep up and tell them that it's safer to continue pumping out derivative sequels.

Toru Hagihara, who acted as both director and producer for Symphony of the Night, had that kind of character (I compare him to Gunpei Yokoi, who passionately guided the Metroid series' development for ten years and did so by thinking outside the box and inspiring his team to carry out unique visions). When I speak of a "missing creative force" in my reviews of the Symphony of the Night-style portable games, I'm referring directly to him.

Hagihara was a visionary, and his thinking was apparently lost on Koji Igarashi, his directorial successor, whose iterative works were high in quality, yes, but unsurprisingly never groundbreaking. Had Hagihara, or someone of his caliber, been around to guide Igarashi's obviously talented team, the series might have continued to evolve in meaningful ways and become the type of revolutionary force that begot considerable commercial success.

Oh what might have been.

In short: You don't want a "Symphony of the Night 2." In this day and age, there certainly wouldn't be a visionary at its helm, and consequently it'd be the same game you've played a dozen times, and it wouldn't be anywhere near as impactful as the original.

I can't accurately guess as to how many times I've returned to Symphony of the Night over the past 17 years. Between all of the full-playthroughs and all of the instances in which I played the game to mine content from it, the number has to be somewhere in the hundreds.

That's how irresistible this game is.

Aside from my desiring to continually re-experience what I consider to be a flat-out amazing action-adventure game, I have another very good reason to return to Symphony of the Night: its astounding depth. Two decades later, I'm still finding new things in this game: new weapon combos; new Sword of Dawn techniques; secret weapon attributes; specially coded messages; Familiars' special attacks; unnoticed graphical details like the fountain's water turning blood-red when it overlaps with the background layer's hovering moon; and Slogra and Gaibon making a Ridley-like appearance in the courtyard if you retreat back to the Castle Entrance immediately after entering the Alchemy Lab.

And I'm sure that there's still tons of stuff that I haven't yet discovered! I'm certain that I'll still be finding things even twenty years from now!

And when you put it all together, you get yourself one of the medium's all-time masterworks. Castlevania: Symphony of the Night is a legendarily great game, and it combines with Dracula X: Rondo of Blood, its direct predecessor, to complete of the best one-two punches in gaming history. It makes a convincing case for being the best game on the Sony PlayStation. And it stands together with Super Metroid atop the pantheon of action-adventure games and helps to form an unapproachable pair.

Honestly, I've never been comfortable with the idea of comparing Symphony of the Night and Super Metroid. I mean, sure: They both occupy the same genre, and they're remarkably similar in design (Symphony unapologetically lifts Super Metroid's map system), but I find that they achieve greatness in entirely different ways.

Each of the two has different strengths: Symphony can't touch Super Metroid in terms of providing an organically flowing, wondrously interconnected world (really, breaking your way through an obviously tattered wall to access a secret room is hardly comparable to finding a hidden item by bombing, speed-boosting and shinesparking your way across entire series of caverns and destructible walls) and haunting environmental conveyance, but Super Metroid simply can't match Symphony in terms of pure action and depth of gameplay.

I don't see one being better than the other, no. More than anything, I see them as two games that strongly complement one another. To me, the action-adventure space wouldn't be complete without their combination.

Now, I'd been warned that the Sega Saturn version of Symphony of the Night (to which I refer as "Nocturne in the Moonlight") was sloppily ported and that its extra content, which was its main selling point, was shallow and superfluous, but I didn't care. I seriously coveted it: I wanted to explore its new areas! I wanted to know what it was like to play as Maria! I wanted to see all of its new enemies in action! And most of all, I wanted to give it proper coverage on my site (I especially desired to snap some screenshots of its action and rip all of its new character sprites!).

So early in March of 2001, I participated in an auction on eBay and won myself a copy of Nocturne in the Moonlight! My winning bid totaled a ridiculous $200, and yes--I definitely had some considerable buyer's remorse in following.

Since there was no way that I was going to spend any additional money to get myself a Saturn, which at the time was running somewhere between $400-500, I had to resort to ripping the CD's contents and playing Nocturne with emulators like GiriGiri, Satourne and Cassini. And I did so at about five frames per second (because in the early 2000s, faithfully emulating the Saturn was apparently impossible).

And its critics, I found, weren't lying: The port was hamstrung by unfortunate control issues and specifically a condensed and thus unfortunately complex input scheme (to be fair, this was more the fault of the Saturn's controller, which had fewer buttons than the PlayStation controller); odd structural changes that begot additional loading times; and other questionable design choices.

But still I had fun playing through the game with Maria and discovering all of its differences. I had no real complaints.

And because I was the type who was fascinated by seeing my favorite games existing in some other form, I enjoyed it from that perspective, too. Its newly added content may have indeed been superfluous, as the critics said, but I liked almost all of it, and I didn't feel as though its presence tarnished the original game's legacy in any way. It couldn't. Because, really, there was nothing that could ever damage Symphony of the Night's reputation. It was too loved for that to happen.

Nocturne wasn't a replacement for Symphony of the Night, no. It was just different. And for that reason, I felt that there was great novelty to it.

I was glad to have it in my collection.

"So tell us, you long-winded freak," you say as you clear the crust from your eyes, if you believe that Castlevania: Symphony of the Night is such an incredible game, then why isn't it your favorite game in the series?"

Well, there are two reasons why it isn't. This first is "length factor." When it comes down to it, I need a Castlevania game to do a job for me. I need it to scratch an itch--to deliver entertainment in a period of about one-two hours, which I consider to be an ideal duration for an action-platformer. Games like Castlevania III: Dracula's Curse and Dracula X: Rondo of Blood do that for me, so I slot them ahead of Symphony on my list of series favorites.

The other reason is that I simply prefer the stage-based Castlevanias. I do so mostly because they actually offer a challenge. Symphony of the Night is, to be honest, a cakewalk, and to me, that hurts its replayability a bit.

But please don't take that to be a slight on Symphony of the Night. It isn't. It's simply an objective judgment of its difficulty-level. On the whole, Symphony is still arguably the series' best game. It's just that the stage-based games do more to meet my needs.

I return to Symphony less frequently than I did in the past mostly because of the length factor, not because it doesn't deserve to played as much as the Metroids, Mega Mans and Marios. But when I do return to it, I'm quickly reminded of its power and why it's so deeply alluring. Because no matter how many times I play it, it never loses its sense of enormity and its feeling of unparalleled grandeur. It reliably delivers the same epic experience.

That's why I treat every play-through of Symphony of the Night as a big event and excitedly prepare for it and schedule it. It's why I always make sure to absorb the game's every enchanting vibe, savor every minute of my epic journey, and constantly delight in the fact that I'm playing one of the greatest games ever made.

I want the experience to feel special, and each time, it dependably does.

So here's to Castlevania: Symphony of the Night: the little budget title that shaped up to be so unfathomably awesome that it turned the gaming world upside-down and transported the action-adventure genre to new heights.

May it continue to reign supreme.

No comments:

Post a Comment