That's been my experience in recent years. As I've eagerly explored video-game history's glittering mines, I've grown ever-more enlightened. The deeper I tunnel, the more I evolve as an enthusiast, and my intense craving for unfiltered knowledge and scarcely documented historical data fuels me and drives me to continue digging.

Truly this is a far cry from my younger days, when I was all too happy to remain completely oblivious to video games' history because I didn't think that there was much to it. I was certain that video games' progression was nothing more than a series of predictable, linear events, and thus I felt that I already knew everything there was to know.

"What I see in front of me is all that there is to it," I thought.

That was how I viewed the world of games.

Yet even back then, more than a quarter of a century ago, there were visible signs that the video-game world was a much larger, more wondrous place than I believed. The first of them was the sudden appearance of a strikingly familiar-looking game that was described to be the "real" Super Mario Bros. 2.

At the time, learning of its existence was one of the most shocking discoveries I'd ever made.

Mario's unpublicized adventure came to my attention in late 1991 on a random day in which I was out shopping with my mother and her friend Audrey. As they were spending their usual small eternity strolling up and down the clothes and appliance sections in whichever store we were in (it was either Walmart or Genovese; I can't remember for sure), I wandered off and headed over to the video-game aisle to check up on the latest NES and SNES releases.

While I was there, I decided to browse through the magazine headlines and get a sense of what gaming publications were currently focusing their energy on.

That's when my eyes happened upon a new arrival called "Mario Mania," whose NES Game Atlas-like paperback cover, stocky build, and unmistakable graphical design clearly indicated to me that I was looking at the next entry in Nintendo's Player's Guide series, of which I was a big fan. I didn't even need to see the words printed on its cover to know what it was or know that I was interested in owning it.

I didn't put any energy into considering whether or not it was reasonable to ask my mother to buy it for me because I didn't care to engage in such rumination. Because I knew, the moment in which the guide's iconic Mario imagery imprinted upon my reptilian brain, that I needed to have it right at that moment and that I was going to get it no matter what. So I made a desperate plea to my mother, and fortunately, she eagerly agreed to my request--perhaps, I think, because she knew that doing so would likely shut me up for the day.

After we were done shopping, we initiated what had become our traditional sequence of follow-up events: We stopped for lunch over at the New Parkway Restaurant over on 13th Avenue, and as my mother and Audrey yammered on and on about their boring "adult" problems, I ignored them and focused all of my attention on my recent gaming-related purchase (usually I'd flip through a gaming magazine or continuously read a game's manual or box descriptions).

This time, the object of my obsession was the Mario Mania guide, which contained a compelling retrospective on Mario's history and his many cameo appearances; and a comprehensive Super Mario World guide, which I knew I'd enjoy poring over even though I'd long since located the game's 96 exits.

So there I was quickly flipping through Mario Mania's guide portion when suddenly I had to stop and backtrack a few pages because I was certain that I'd caught a glimpse of some imagery that was familiar-looking but at the same time somehow alien in appearance.

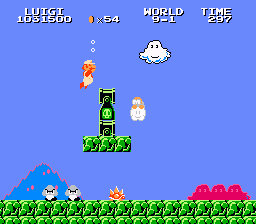

The images in question belonged to a specially designed sidebar titled "Super Mariology," which in a did-you-know fashion spoke of a "Japanese version" of Super Mario Bros. 2. It wasn't talking about the Arabian-themed classic that we all knew and loved, mind you, but rather an original work that had never graced our shores!

There wasn't much to the article, really--there were only four small screenshots and maybe five sentences' worth of information--yet for me, nothing more needed to be said. Because just that tiny sliver of info, alone, was enough to absolutely blow my mind!

In that moment, I had so many questions: "How is it that I've never heard about this game until just now?!" "Why was it never considered for release in the US?!" "Why is it so graphically similar to the original Super Mario Bros.?!" "What the hell is 'Doki Doki Panic,' and what does it have to do with the Super Mario Bros. 2 that we've been playing since 1988?!" "And what's with that weird, cobbly-looking floor texture?!"

I was both excited and fascinated by what I was seeing and reading. "It's unbelievable that such a game exists," I thought to myself, "and that's it's been out there all this time without anyone knowing about it!"

I felt as though I'd just gained exclusive knowledge of an incredibly mysterious secret treasure!

At the same time, though, my excitement was tempered a feeling of defeat because I knew that nothing would ever become of this discovery. After all: There would, I was sure, never be an opportunity for me to play this game. The reality was that Japan was a world away, and there was a zero-percent chance that I was ever going to find a way to gain access to its goods.

That's why it felt all the more exhilarating when Nintendo Power Volume 52 arrived with news of Super Mario All-Stars: a compilation that was said to include 16-bit remakes of the three classic NES Super Mario Bros. games plus the never-before-seen, curiously named "Lost Levels," which, sure enough, was one and the same with the "Japanese version of Super Mario Bros. 2" that I'd read about eons earlier (a year and half before, in actuality)!

The preview put a heavy emphasis on Lost Levels and explained in detail how it was different from the original Super Mario Bros. It expanded upon what the Mario Mania article had revealed and stressed that the games' difficulty far exceeded its predecessor's and reiterated that it introduced some new mechanics that worked to turn the original game's formula on its head and, apparently, gleefully betray its every value.

The piece explained how the game did so: It said that there were poison mushrooms that would "take away Mario and Luigi's powers" (in reality, they simply inflicted plain-ol' contact damage). There were eastward wind-gusts that push the brothers forward and alter the momentum of their jumps. And there were even warp zones that would send them back to previously completed worlds!

And honestly, it all sounded very interesting to me. I was glad that the game found ways to differentiate itself, and I didn't suspect that any of its new additions would actually give me as much trouble as the preview claimed they would. (Because how could I have really known?)

The piece also revealed that Lost Levels contained five extra worlds and that the brothers had different physical abilities. Basically Luigi could jump higher and farther than Mario, just as he could in our version of Super Mario Bros. 2.

And I was thrilled that the two Super Mario Bros. 2-titled games shared this connection. In my mind, this single mechanical similarity canonized the US version as a true Super Mario Bros. game. It proved that the US version had a clear connection to the established Super Mario Bros. universe and wasn't merely a lazy sprite-swap of this "Doki Doki Panic" game.

I felt that it was important for me to engage in this way of thinking because I loved the US version of Super Mario Bros. 2 and I was fearful that people would point to Lost Levels' existence as proof that the former wasn't a "real" Super Mario Bros. game.

Those types were going to show up eventually, I knew, and I wanted to get ahead of them!

I'd always had an aversion to remakes because I saw them as unnecessary. "Upgrading a game's graphics doesn't make it 'new,'" I felt. "And it's silly to buy a game that you already own!"

But I found a reason to make an exception for All-Stars. I rationalized that I was buying because I wanted to gain access to Lost Levels, which was visually similar to Super Mario Bros., yes, but otherwise a completely new game. And the rest of the games were simply "strong bonus content."

I mean, $50 for a compilation that included a fascinating Japan-only game and recreations of three all-time classics? That sounded like a great deal to me. So I concluded that buying All-Stars would be a fine way to use my recently obtained birthday money!

And like I said: Lost Levels' difficulty being described as "a natural continuation of what you experienced in the original Super Mario Bros.'s World 8" didn't sound too bad to me.

"I'm able to blast my way through World 8 without feeling the least bit stressed," I said to myself, "so really there's probably nothing in Lost Levels that can pose a serious challenge to me!"

"This is me we're talking about here!" I stated with great confidence. "I've beaten some of the hardest games ever made! So surely a merely 'more difficult' Super Mario Bros. won't cause me much trouble!"

Oh, I had no idea what I was about to get myself into.

So the first time I played Lost Levels, I did what felt natural: I selected to play as Mario, which was what you did, traditionally, the first time you played a Super Mario Bros. game. Because after all: It had always been true that Mario was the "balanced character" for whom the games' level design was actually crafted. The games' stages were structured with his abilities in mind.

"Thus the same has to be true of Lost Levels!" I was certain.

And then I pressed the Start button and learned within moments that I was gravely mistaken and that Lost Levels didn't give a damn about adhering to conventional design methods. It was rather blunt in advertising that it had no desire to issue a single shred of mercy, and thus it sent me a clear message that I would need to exhibit nothing short of mastery over Mario's maneuverability and jumping mechanics if I hoped to clear even a single world while playing as him.

Half the time, I didn't even feel as though Mario was capable of making required jumps. Some gaps appeared to be too insanely long to be cleared by even his fully extended jumps, and when I was actually able to clear such gaps, it was always just barely--by maybe a single pixel.

"Is this game even made for him?" I wondered at times. "Is it even possible to beat it with him?"

When I was playing as Mario, each stage felt like a series of rough mini-challenges, and so much had to go right for me if I wanted to reach the goal. And after I endured about an hour's worth of agonizingly deflating missed jumps and piranha-plant-inflicted deaths, I shouted, "Screw this!" Then I decided to reset the game and this time play exclusively as Luigi.

"Because I'd be crazy not to do that!" I thought to myself.

I figured that if Luigi functioned anything like he did in the US version of Super Mario Bros. 2, then I'd have a much different experience. The game would be a cakewalk.

But then, to my great horror, I immediately learned the hard way that Luigi had been assigned an extremely obnoxious quirk: Upon breaking his running momentum or landing from a long horizontal jump, you'd uncontrollably skid along the surface at about a distance of two blocks before your movement would finally cease! (For comparison, Mario only skid about half a block's distance.)

This would often result in his sliding off of targeted platforms, usually to his death, or his (a) flying through the air in an uncontrollable manner whenever I'd attempt to stabilize his movement by executing a follow-up jump and (b) likely landing in a death pit!

I really thought that the "Luigi Game" experience would be similar to the one that I usually had with the US version of Super Mario Bros. 2, in which I could use Luigi to effortlessly and joyously launch myself across environments and trivialize even the most menacing-looking of jumps. But it absolutely wasn't. It was more like playing as a drunk Sonic the Hedgehog and trying to traverse a world whose every surface had ice physics.

So instead I spent the new few hours continuously slipping off of every platform in sight and badly miscalculating jumps because I kept overcompensating for potential skidding.

And the result was that this was turning out to be a nightmarish gaming experience.

I understood, of course, that the designers assigned Luigi this detrimental quirk with the intention of limiting his game-breaking propensity and creating a sense of balance between the brothers, but it was apparent to me that they clearly didn't get the result that they were looking for. Rather, they wound up creating two undesirable options!

"There had to be a better solution," I thought.

And it should really tell you something about Mario when I say that Luigi, for all of his shortcomings, was still a far-superior alternative. I mean, seriously: I had no clue how anyone could be expected to complete the game with Mario. I had no intention of even trying to do so; rather, I decided that it was in my best interest to never play as him.

What drove me to continue playing on was the game's fascination factor. It was obvious to me, even early on, that the game was determined to break all of the rules, and I was interested to know all of the ways in which it did so. I was interested to know the limits of its lunacy.

And it was out there, man: It had the normally aquatic Bloopers floating around in the air. It had fire bars in non-castle stages. It had Koopas and Koopa Paratroopers patrolling around in underwater stages. And it even had land stages that were submerged for no clear reason and thus completely unchallenging because you could just swim over all of their enemies and obstacles!

Lost Levels truly was the bizarro Super Mario Bros., and the whole time I was playing it, I couldn't wait to see what crazy thing it was going to hit me with next!

My only hope was that I didn't suffer an emotional breakdown before I got the chance to see it.

That, really, is why I vividly remember my first experience with Lost Levels. I do so not because I recall how excited I was to be playing a "lost Mario game," no, but rather because I recall how the game almost drove me to the brink of madness.

I still remember the challenges that inflicted each individual wound. I can still clearly visualize the long, ridiculous jumps that required me to thread combinations of fire bars and flying enemies; the narrow three-tile openings that were so hard to gain entry into that doing so seemed to come down to chance; the insane launching-spring stages, in which I struggled to land where I wanted to because I could never tell where the hell I was as I hovered offscreen; and the windy segments that only exacerbated Luigi's sliding quirk and rendered platforming an exercise in soul-killing frustration.

Then there were the awful maze-based castles (which I imagined were exceedingly difficult to figure out without the remake's generously provided aural cues); the friggin' omnipresent Hammer Bros., many of which were programmed to unyieldingly march forward and bedevil players who were lacking fireball power; the millionth instance in which a Paratroopa appeared at the screen's edge just in time to collide with me as I was landing from a lengthy jump; and the 8-4 castle, whose ridiculous wraparound jumps did me in time and time again and forced me to continuously repeat the previous three stages, in what quickly grew to become a tedious exercise, just so that I could get another shot at negotiating them (or "failing to negotiate them," as it usually went).

It all amounted to an exercise in extreme frustration, and during my play-through, I spent most of my mental energy wondering what the hell was wrong with the people who made this game.

Lost Levels was, in every way, the complete antithesis of Super Mario Bros. It was neither accessible nor fun, and it had no ability to evoke feelings of happiness or joy. Rather, it was designed specifically to be spiteful and cruel and make players feel angry and dispirited.

Hell--Worlds A through D were so rough that I considered them to be grade-A Game Genie material. It was just unfortunate that such a product didn't seem to exist.

But still I was determined to beat Lost Levels. So I did was was typical for me: I locked myself in my room and put myself through the grinder. I abandoned all sense of restraint and persisted until the deed was done, and all the while, I used my escalating feelings of anger as a driving force. And it was a mighty struggle, as Lost Levels proved itself to be one of the toughest, meanest games I'd ever played.

I was honestly scarred by the experience.

All I can say is thank goodness for the game's generous continue system. Had it not allowed me to continue from the stage in which I died, I might've yanked its cartridge from my SNES and punted it across three boroughs.

Years later, I learned that Lost Levels didn't see release in the US because Nintendo of America balked at the idea of bringing a over a Super Mario Bros. game that was unfairly difficult and also highly derivative and graphically dated by 1988's standards.

Normally I'm one of the biggest critics of Nintendo of America's 80s- and 90s-era decision-making, but I have to give credit where it's due: The company made the right call here. Lost Levels was the most uncharacteristically uninviting, cruelly designed big-name sequel that Nintendo had ever produced, and it probably would have tanked the entire series in all other territories.

Because of that decision, we got a far-more-desirable outcome: Here in the West, we got our own wonderfully unique Super Mario Bros. sequel, and later on, we got the chance to play the original work in a much-more-palatable form and experience it as cool bonus content in a fantastic remake compilation.

We arrived in a situation in which we were able to access two vastly different versions of Super Mario Bros. 2, each of which was fascinating in its own distinct way!

It wasn't until the Internet age that I got the opportunity to play the Japanese version of Super Mario Bros. 2 in its original 8-bit form. I messed around with it via FDS-compatible NES emulators, but for whatever reason, I never felt compelled to actually play through it or spend more than a few minutes with it. (I'm guessing that traumatic memories of my earlier experiences with the game would eventually start to surface and ultimately drive me away.)

I didn't get serious about playing the original version until 2014, after I decided to purchase it from the 3DS eShop.

It just felt like the right time to do so. Because I'd recently started up this blog, and I viewed the Japanese version of Super Mario Bros. 2 as the kind of game that encapsulated all of its essential qualities.

I reasoned that if I wanted to be serious about identifying as a gaming historian, I had to do what was incumbent upon me: play through the game in its original form and get a true sense of what it was.

Also, I had to admit that I still found the game to be very alluring despite the fact that I had a distaste for its style of level design.

I compared it to those like Rockman & Forte and Adventure Island IV--highly mysterious "lost games," playing which made me feel as though I was breaking the rules and finding a forbidden way to access games that weren't meant to be seen by my Western eyes. It, too, had the ability to evoke that feeling from me and captivate me in the same way.

Even when I didn't particularly enjoy playing a game of its type, I was still able to extract some form of enjoyment from it by enthusiastically fixating on its lost-artifact qualities and delightedly absorbing its uniquely nostalgic vibes.

Super Mario Bros. 2 was loaded with both, and that's why I was drawn to it.

I played through it a bunch of times, and usually I took the shortest path--particularly so during the first week, when I used warp zones to more quickly complete it the eight times necessary to access the special lettered worlds, which were otherwise unlocked by default in the All-Stars version.

As I was doing so, I found that I was genuinely enjoying myself, and soon I arrived in a position in which I could no longer deny the truth: I actually really liked Super Mario Bros. 2!

Though, I couldn't provide any sane-sounding explanation for why that was.

I mean, look at it: It's largely inaccessible. It's rarely intuitive. It's cruelly designed. And it's too damn difficult!

It is, in many ways, an insult to its legendary forebear, and it sometimes comes off as a hateful imposter that's masquerading around in the latter's shell.

Yet so help me, I actually like it!

Even though it frustrates and annoys me at times, I enjoy playing it and taking on its challenges, and I derive pleasure from running around its world and observing it and letting it remind me why I love to discover lost games.

I can't say that I'm fond of how it betrays its forebear's values, no, yet still I love that it exists. It's a fascinating game, and I love what it represents: It shows us that the medium's history is filled with strange and wonderful hidden treasures that are out there just waiting to be discovered.

It's filled with games like Super Mario Bros. 2, which I'll remember most for how it gave me my first glimpse into a world that was far more expansive than I'd ever imagined.

It was the first of the many discoveries that changed the way I viewed video games.

No comments:

Post a Comment