Skeletons, hunchbacks and wolfmen? What Dark Lord needs 'em when he has the greatest ally of all: incompetent game designers.

It was an improbable comeback for Castlevania. The game series that I'd tossed aside and deemed to be completely unworthy of my time and attention made an unexpected, highly aggressive push and succeeded in showing me that I absolutely needed to have it in my life. And after it accomplished that feat, it quickly became one of my favorites.

It all started in the winter months of 1990, when Castlevania III: Dracula's Curse, which I'd previously disregarded, found its way into my home thanks to a series of amazing coincidences (or perhaps it was guided there by fate) and quickly became one of my favorite games. In a short time, it took over my life and deeply engrossed me with its top-tier action and wondrously presented world of mythology, magic and monsters, and consequently it helped me to see the Castlevania series in a new light.

And with newly trained eyes, I returned to the original Castlevania, which I'd previously sworn off, and was finally able to recognize its genius. Thus, it, too, became another one of my obsessions. (You can read a more comprehensive version of this story in my Dracula's Curse piece.)

Over the next few months, I continued to bounce back and forth between the two games. I couldn't stop playing them. My hunger for Castlevania-style action couldn't be satiated. I always wanted more of it. I was always looking for new ways to experience it.

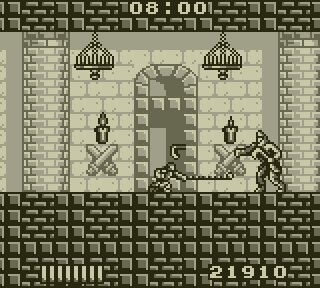

It was just a bit of good fortune, then, that the series' next installment had already been released! It was called Castlevania: The Adventure, and it was available for the Game Boy.

At the time, I didn't know much about Adventure (it had been previewed in Nintendo Power a bunch of times, yeah, but I never paid much attention to those pieces--mostly because I wanted nothing to do with the series after my soul-crushing experiences with the original Castlevania), but still I was very interested in owning it. I mean, I had an insatiable appetite for Castlevania action, and I was growing increasingly fond of the Game Boy, so purchasing Adventure seemed like a no-brainer. "It's exactly the game I need at this point in time!" I thought to myself. And because Nintendo Power's promotional pieces appeared to give the game a ringing endorsement, I felt confident in my decision to buy it.

All that was left for me to do was beg my mother to take me over to Toys R Us the next day, in the after-school hours, so I could pick up a copy of Adventure.

But after I reflected on the matter for a couple of hours, my fears began to fade away. "I shouldn't be worrying about any of this," I reasoned. "I mean, this game is made by Konami, which has been on an absolute roll in recent years! I've loved every one of its releases. So what could possibly go wrong?"

Well, everything.

I was immediately off-put by how Adventure's action felt. It was sluggish as hell. The game's hero, Christopher Belmont, advanced forward as though he were wading through quicksand with 50-pound weights tied around his ankles, and resultantly, the controls felt stiff and unresponsive. Most times, the controls wouldn't respond at all; I'd press the attack button and Christopher would just stand there and do nothing.

Also, the stage's background would, for some reason, blur horribly whenever the screen was scrolling, and my eyes would strain whenever I would focus on a moving background.

"What's going on here?" I wondered. "Why is this game moving so damn slowly?!"

I was almost convinced that my copy of the game was defective.

On the surface, Adventure bore a strong resemblance to the NES Castlevanias, but in reality, it was quite a different beast. So much of it was weird and unfamiliar. The enemies, for instance, were nothing like those I'd encountered in the NES games, and I didn't know how to feel about that. I didn't know what to make of enemies like the strange amorphous blobs that would plop down from above and then take humanoid form. The game's manual identified them as "Madmen," but that label failed to adequately describe what they were.

"Are these guys supposed to be zombies or mudmen or maybe an amalgamation of the two?" I wondered. The word madman brought to mind images of deranged psychopaths and reckless crazies, but these slime-soaked ghouls didn't seem to be either; rather, they were contrastingly quiet, unexpressive blob creatures that slowly walked forward and did so like they were fighting wind-tunnel-level resistance. It didn't make any sense. "Why not just use standard Castlevania-style zombies instead?" I questioned. "Why change the character to something unrecognizable and then completely mislabel it?"

That's how it was with all of the enemies. I didn't know what they were or why they were replacing the standard series characters. As I advanced through the first stage, I kept wondering, "Where are the usual skeletons, knights and fishmen?" They weren't there. Instead there were only walking globs of goo, entirely featureless "goblins" (as I identified them) that would snap back when they took damage, and giant rolling eyeballs that would explode when I whipped them. "What the hell are these enemies supposed to be?" I kept asking in confusion.

Also, none of the game's candelabra-held items functioned in a traditional manner, which only served to further confuse me. Now, I didn't have a problem with the idea of designers making gameplay changes in an attempt to keep the action feeling fresh, no, but that wasn't what they endeavored to do here. Rather, all they did, inexplicably, was make pointless cosmetic changes. They merely swapped morning-star symbols, pot roasts and money bags for crystals, hearts and coins, all three of which functioned in the exact same way as the former. "Why do this?" I wondered. "Why make such pointless, confusing deviations?"

"And why did they use hearts as heath-regeneration items rather than as fuel for sub-weapons?" you ask. Well, because there were no sub-weapons! The designers forgot to include them! Somehow, they couldn't find time to add in an essential series element.

There were so many bizarre design decisions, and all they did was make me feel as though Adventure's creators were working without any knowledge of the script.

Adventure couldn't get anything right. It just kept falling short of expectations. And even when it did manage to do something genuinely cool or interesting, it would quickly and invariably sabotage itself. It, for instance, introduced the great idea to have the level-3 whip spew fireballs--a power that provided Christopher a ranged option that helped him to compensate for the lack of sub-weapons--but then promptly ruined it with a whip-regression system, which dictated that the whip's power downgrade one level any time you took damage. It replaced stairways with climbable ropes, which would have been fine had it not prevented you from whipping while climbing--a perplexingly bad design choice that served to render you helpless in scenarios in which enemies or projectiles were coming at you from the side as you were climbing.

It was like that with every newly introduced system or mechanic. There was always some dumb, punishing limitation attached to it.

In those first few minutes, Adventure made a really poor impression on me, and consequently all I could do was stop and wonder about what went wrong. I could only conclude that the Game Boy, as I'd feared, just wasn't capable of producing a console-quality Castlevania game.

Though, I wasn't completely down on Adventure, no. In truth, I was actually very impressed with certain aspects of it. The first was the background work. I was quite taken by it. It was sharp- and crisp-looking and finely detailed, and, most importantly, it did a great job of producing the type of eerie, mysterious atmosphere that I expected a Castlevania game to exhibit. Going in, I didn't think that a Game Boy game would be capable of meeting that standard.

I loved, in particular, the imagery in the opening stage's backgrounds. I enjoyed observing and examining its spooky woodland elements, its dreary graveyard scenes, and its massive, awe-inspiring mountainscapes (I was always a sucker for mountain visuals in video games). Each one was able to stir my imagination and evoke feelings of wonder. And that's exactly what I wanted from a Castlevania game.

Also, I was fond of how Adventure sounded. Its music was appropriately spooky- and ominous-sounding, and thus it perfectly augmented the eerie, mysterious visuals and made the game's world feel all the more haunted. And its sound effects provided some additional character. The best was the ghostly wailing sound made by the ravens whenever they'd fly onto the screen; it was creepy in an unsettling kind of way, and I appreciated it for that reason.

So I had to give the game's visual and sound designers a lot of credit. They really nailed the atmosphere and the setting.

It was just too bad that the rest of the team had trouble keeping up.

I sensed right away that Adventure was going to be a difficult game, but I assumed that it would be so for the expected reasons. I didn't imagine that its difficulty would instead derive mostly from questionable level-design choices. My first warning of such was a platforming challenge encountered in Stage 1's latter half--a segment in which you had to jump across three darkly colored floating platforms. I knew, instinctually, that the platforms were going to collapse when I landed on them, but I had no idea that they were going to instantly drop like a sack of wet bricks and thus provide me no time to orient myself and prepare for the next jump.

The message was clear: The designers knew that Christopher's jumps had limited range and an above-average amount of landing lag, and they were keen to use these limitations against me and do so in sadistic fashion (and it didn't help that the game's slowdown issue made it harder to time and execute jumps).

The problem was that Adventure expected pixel-perfect accuracy. You couldn't just jump from where you landed, no; if you wanted to reach the next platform in line, you had to move to the currently occupied platform's extreme edge before executing your jump. That was hard to do in a game that had indiscernible platform-edge collision detection and serious slowdown issues. And since I hadn't yet adapted to the game's slow speed or gotten a grasp on its collision detection, I struggled with the platforming segments. My first couple of platforming attempts entailed walking off cliffs, panicking and jumping way too early, and coming up short because I dared to jump before reaching a platform's very last pixel.

That was the thing with rough, poorly designed games: They didn't waste time. They started inflicting the pain very early.

But that wasn't even the worst of it. A bit later on, there was platforming segment that almost broke me. It was formed from two sets of very narrow platforms, and it stretched on for miles.

I'm telling you: This one was the main course in one of the most sloppily prepared, nausea-inducing meals I'd ever had.

What you were required to do was jump from one narrow platform to the next and do so with pixel-perfect precision. If your timing wasn't perfect, you'd come up short and fall the ground below. And if you missed any single jump, you'd have to backtrack all of the way back the segment's start and try again.

In a minutes-long stretch, I repeatedly failed to clear this segment. I kept mistiming my jumps and missing them, and in plenty of instances, I fell through a successive platform's edge even though I jumped as late as possible and seemingly covered the distance. And each time, I had to slowly and wearily backtrack my way to the start.

It didn't help that obnoxious fluttering bats were positioned at each platform set's midpoint. These winged terrors would suddenly spring to life and then proceed to fly overhead, out of my whipping range, and continuously bump into me. There was nothing I could do to combat them. Christopher didn't have any anti-air options; he could only whip straight ahead. So all I could was hope that they would fly away from me and eventually descend down to head- or chest-level. They rarely did; they'd just keep flying overhead and bumping into me from above. So I'd try to tank my way forward and resultantly get knocked into gaps.

The segment's jumps, on their own, were already harrowing enough, but its demanding that I deal with highly aggressive bats at the same time was too much; it was completely ridiculous.

The best way to deal with the bats, I found, was to backtrack a bit and give myself the space I needed to deal with them. But when I'd do that, the bats would respawn the instant I'd scroll the screen forward again! One way or another, the bats would get me, and the result was that this segment had a considerable energy-draining factor to it.

On the whole, this segment was one of the most infuriating things I'd ever encountered in a game.

And when I finally made it to the Stage 1 boss, Gobanz, I was too depleted to put up a fight. I was low on health, and my whip was at base-level, which meant that it was too short in length to offset Gobanz' range advantage and too weak to produce a win in a close-quarters slugfest. That's how it was every time I made it here; I was always in the same position.

One of the problems was that the Game Boy's screen had a low resolution, and thus the boss room was small and cramped. There was little room to maneuver. And it didn't help that the monstrous Gobanz took up about a third of the screen. It was tough to work around him. Doing so was difficult because he could thrust his spear diagonally upward and effectively limit any of my tactical maneuvering. Also, he had the propensity to crowd me into corners and stunlock me with successive strikes.

In truth, it only took me about three or four attempts to defeat Gobanz and complete the stage, but even then, it was a real struggle, and I was greatly concerned by what I'd experienced. At that point, I had to stop and wonder, "If it's this bad in Stage 1, how crazy is it going to get later on?"

If only for moments at a time, I could find comfort in enjoying Adventure's visuals and music. That's what I did while I was traversing Stage 2's tamer portions. I took the opportunity to appreciate its wonderfully chilling musical theme and entrancingly eerie cave setting and admire how they worked together to tell the intriguing story of a haunted, neglected underground cavern.

Soon, though, I'd get back to being frustrated and annoyed with the game's cramped level design and the designers' penchant for mischievously positioning bats in overhead positions.

It wasn't long before it became obvious to me that there was no point in trying to combat the fluttering menaces. There was no way to reliably engage with them--especially when they were attacking in groups and coming at you from all angles. So it became my strategy to simply tank my way past them and hope to take as few hits as possible. Sometimes I'd get lucky and come out largely unscathed, but usually I'd get caught in a net and bounced around repeatedly.

At one point, I started to think that the designers had a fondness for using the same nasty tricks over and over again and didn't care how badly such tricks were perceived. "They must want you to know that their horrible enemy-positioning is deliberate," I thought. "That's probably why they keep placing bats on ceilings."

Surprisingly, though, the following stage areas had some thoughtfully designed, manageable enemies and platforming segments. And a couple of them were quite creative. There was the cool boomerang-tossing Zeldo--the series' first "mini-reaper," as I classified him (I was certain this his name was some type of reference to The Legend of Zelda series, since both he and Link shared a similar taste in weaponry). There was the appropriately grotesque hand-shaped Punaguchi, which spit out rebounding balls of globule. And there were cool bridge segments in which you had to carefully engage their occupants--the Rolling Eyes, whose explosive deaths would destroy sections of the bridges' surfaces and potentially leave gaps that were too long to clear (which would happen if you killed two Rolling Eyes that were close in proximity); these were interesting pick-your-poison-type challenges in which you had to choose between taking out the Rolling Eyes and dealing with the consequences of such or attempting to safely jump over them, which was tough to do. Doing the former, I concluded, was too risky, so I decided that the better tactic was to simply jump over the eyes.

But the Rolling Eyes' destructive explosions was a neat effect and something that helped Adventure to stand out from the NES games. Things like that and the cool, inventive enemies helped me to come terms with the game's divergent qualities. I mean, I continued to be disappointed with the game's lack of classic enemies like skeletons, bone pillars, knights and Medusa heads, yeah, but still I couldn't think of any good reason to be angry about the designers' efforts to differentiate their enemy cast and provide their game a unique personality. I respected the effort.

Of course, none of this made playing the game any more fun, no. Having to dodge tricky, fast-moving boomerangs and bouncing balls of globule that would seemingly appear out of nowhere was just as maddening as 95% of the game's other challenges. And what was worse was that all of the projectile appearances and explosions were causing the game to slow down even more and eat inputs at an even higher rate!

Naturally, the areas in following contained more in the way of collapsing-platform sequences, all of which I struggled to clear. I failed over and over again, and each time, I had to restart from the beginning--from the stage's nightmarish bat-infested opening area. It was aggravating as hell. And because it was a requisite that each of Adventure's stages had to have at least one terribly designed segment, you couldn't clear Stage 2 without first being forced to traverse a confusing maze--two consecutive Lost Woods-style labyrinths. If you took a wrong path here, you'd loop back to a previous maze section or, more cruelly, the start of the previous bridge area!

Now, the bridge area wasn't too long, no, but its enemies were proficient at draining my health, and that was a problem because I needed to have a fair amount of health if I hoped to endure the maze, which was filled with inconveniently positioned bats and Punaguchis. So I couldn't afford to make too many trips across the bridges.

It was all too much. I just couldn't survive. And after I failed in the same spot a countless number of times, I angrily switched off the game and didn't return to it for a few days.

In that time, I determined that Adventure wasn't the kind of game that I'd like to play while on the road. It didn't have "road-game" qualities: a fast pace, solid controls, and a manageable difficulty. It needed to be played in a more appropriate space--in a calmer, more-controlled space: at home, in our quiet, sunlit living room, which lacked sufficient lighting (because refracted sunlight had only limited intensity) but made up for it with a permeating feeling of warmth and a comfortable atmosphere that was perfect for playing portable games.

Each time I'd play Adventure, I'd get further into it. I'd make significant progress. But the problem was that I wasn't having any fun. Rather, it was a painful grind, and I was subjecting myself to it only because I was a Castlevania fan and I felt obligated to see the game through to the end. Over the years, I'd developed a warped philosophy whose rule was that you had to complete every game from your favorite series if you hoped to extract maximum value from said series. And I was bound to that philosophy. For me, leaving a series game unfinished was tantamount to missing out on an important piece of a grand story, and doing so would only serve to dampen my enjoyment of future series entries. Moreover, since I'd spent my own money on Adventure, I felt that I needed to complete it justify my considerable monetary investment.

First there was the matter of completing Stage 2. I did so after figuring out how to clear the maze-like final segment and learning how to correctly position myself during the battle against the stage's boss creatures--the crevice-inhabiting, high-jumping Undermoles, which I felt were the most unbecoming Castlevania bosses ever. "This 'boss' is nothing but a pack of indistinguishable rodents!" I thought to myself. It was a disappointing choice of boss for that reason and also because Adventure, according to what I'd read, had a very low number of bosses. Having one of a limited amount of bosses be a pack of lowly rats instead of a large, visually striking creature--like a Frankenstein- or Leviathan-type monstrosity--was, I felt, a highly questionable decision.

Then there was the worst of it: Stage 3--a trap-filled tower (which, originally, I mistakenly identified as a "Clock Tower"). My story with Stage 3 is one of fear and loathing. It was an absolute horror of a stage, and it impeded my progress for months.

Stage 3's opening section, with its compacting spike-lined surfaces, was nothing to sweat, and that, in itself, was the biggest trap. It was a leisure cruise and gave me a false sense of what the stage was; it gave me no indication that what lied ahead were some of the most terrifyingly awful, most wretched challenges I'd ever face. What followed were two incredibly torturous, excruciatingly slow autoscrolling chase sequences that tasked me with using inconveniently placed ropes and platforms to outrun vertically- and horizontally-moving spiked walls. And I had to do this while contending with (a) irritating, cruelly positioned worms that would roll into me, unavoidably, whenever I struck them with a low-level whip, and (b) unending series of unforgiving, nerve-wracking platforming challenges.

And you had to traverse these segments in a very specific way. You had to move at just the right speed. If you moved too deliberately, the spikes would catch up to you and kill you instantly, but if you moved too quickly, you'd bump up against the screen top's invisible boundary during jumps and thus bonk your head and fall short of the mark.

I couldn't believe how ridiculous these segments were.

It wasn't long before I learned to fear Stage 3. I'd explain how poorly it went for me in the hours I spent traversing it, but I'd rather not recall all of those traumatic memories. All I'll say is that I died a countless number of times in those autoscrolling sections.

In that period, I made it to the boss one time and promptly got destroyed--mostly because I was paralyzed by the thought of having to somehow endure a tense, difficult boss battle when I'd just finished being through hell and I was mentally exhausted. I don't think I scored a single hit. And the battle was so short that I didn't have enough opportunity to identify any of the boss' attack or movement patterns. And just one soul-crushing defeat at the hands of this clawed beast was all that was necessary for me to realize that this was about as far as I was going to get in Adventure. After accepting that fact, I defeatedly switched off the Game Boy and pulled out the Adventure game pak.

At that moment, I was convinced that I would never achieve ultimate victory.

For a year in following, my lasting memory of Adventure was what I'd faced in Stage 3--how I'd been subjected to a mentally draining slog through a brutally designed autoscrolling segment and destroyed by the seemingly unassailable boss: the "Death Bat," whose terrifying shape imprinted on my brain. I remembered him as "the stage boss that I had no chance of defeating."

As Super Castlevania IV neared its release date, my enthusiasm for the series started to rocket toward its peak. I was stoked about the idea of getting to play a big new entry in one of my favorite series. Though, I knew that I wouldn't be fully prepared for its arrival until I took care of some unfinished business. I wouldn't be where I needed to be until I played Castlevania: The Adventure to completion!

Now, I'm not sure how it happened, but in one particular run (out of dozens), I somehow made it all of the way to Death Bat with maximum health and a fully-powered whip. And then I managed to defeat him in a battle of attrition (a skillfully achieved victory was out of the question because I was simply incapable of dodging his swooping attacks).

And let me tell you: I was excited to set my eyes on Adventure's final stage, which had eluded me for so very long. As I moved about its opening screen, I felt as though I was walking upon sacred ground. That's how surreal it was.

I wasn't feeling very confident, no, and I feared that what lied ahead was far worse than anything I'd seen previously, but still I was happy to be on the final stage. I was eager to find out what surprises it had in store for me.

Stage 4, in continuing the trend, welcomed me with entrancing, appropriately ominous music and engaging visuals. Its main visual was an assemblage of knight statues, each of which was placed between two of the pillars that formed a series of arches, and it served to create a strong air of finality. "I'm at Hell's door now," I thought.

Some of the knights popping out from the background? I saw it coming. I'd been around the block. But still I liked the idea of it; I always thought it was cool when enemies would pop out or run from the background. Also, I was pleased to finally see a familiar-looking enemy! It took long enough for one of them to appear.

And for a while, I was pleased with how events were unfolding. "This is looking like a fun stage!" I thought.

But as I advanced into the opening section's second half, my excitement turned into apprehension and then into despondency. Suddenly something very concerning happened. "Oh no!" I thought to myself as I watched Gobanz march his way onto the screen. "This game is now using bosses as minor enemies, just like Castlevania did with the Phantom Bat!"

Immediately I remembered how badly I struggled with the latter.

Though, surprisingly, this Gobanz went down easier than the one I faced in Stage 1. Still, his appearance worried me. I interpreted it as a dire warning that Stage 4's difficulty was now going to spike to obscene levels.

And I was right to think as much. Stage 4, I learned over the next 10-20 minutes, was brutally tough. It was basically a lengthy endurance test that featured series of narrow passages that were packed with the game's toughest, most resilient enemies; spike-lined rooms that you had to traverse via moving platforms; rooms in which you had to use long spiky protrusions as platforms; and every other cheap tricks the designers could muster. It was a total grind.

Then I ran into the ultimate roadblock: a single room that contained three Gobanzes! This room was absolutely killer.

I could never make it to that room with level-2 or -3 whip power, which was all but required at that point. You needed it if you hoped to cleanly defeat the Gobanzes and make it to the next section. Now sure--there was plenty of space to take out the first Gobanz, and you could do it even you had a weak leather whip; all you had to do was sneak in shots and tactically retreat--drag him all of the way over to the room's right wall if you needed to.

The problem was that you couldn't employ this same tactic against the second and third Gobanzes. If you dragged a Gobanz more than one screen over before killing it, it would respawn; and it was likely that the previously encountered Gobanz would respawn, too. Then you'd be sandwiched. And there was no way in hell you were going to be able to fight two of these big boys at the same time.

I couldn't get past this room. The Gobanzes would always destroy me. Sometimes, as a last resort, I'd attempt to tank my way past them, but it would never work. Even if my health meter was full, they'd invariably cut me down.

So in Stage 4, the only thing I could "achieve" with any regularity was death. I suffered the same fate over and over again no matter what approach I took.

Inevitably I'd quit and then try again a few days later, and each time, my campaign would end the same way: I'd die multiple times in the Stage 4's multi-Gobanz room and then give up. No matter how many times I replayed the game and no matter how much I improved my skill (I got to a point where I could complete the first three stages without much trouble), I couldn't make advance any further; the Gobanzes would consistently carve me up and end my quest to destroy Count Dracula. And this was as far as my younger self ever got in Castlevania: The Adventure.

Under normal circumstances, I probably would have never returned to Adventure. Usually I avoided punishingly difficult games; I didn't see the value in playing them. The only reason I revisited Adventure--the only reason I had to revisit it--was because I needed to capture some screenshots of its action for the purpose of providing it sufficient coverage on my recently created Castlevania site. And during that effort, I had to cheat my way to end; I had to use save-states to get past the multi-Gobanz room, which was still giving me huge trouble.

I knew what was waiting for me at the stage's endpoint. I'd seen videos of people fighting Dracula. And let me tell you: I had no earthly idea how the designers expected me to survive all of it--how they expected me to endure the insane Gobanz gauntlet and then a two-phase battle with with a final boss that was, from what I could see, the series' most formidable. "There's no I can do this legitimately," I thought. "I have to use save-states to get through this."

And that's how I played Adventure in the following years. I played it on an emulator and used a copious amount of save-states. I felt that I had no choice but to do so. I couldn't envision any scenario in which I could legitimately fight my way through the multi-Gobanz room and retain enough health to endure Dracula's monstrously difficult second form--a nearly unassailable giant bat.

Though, I never felt good about having to resort to such unsavory methods, and my inability to claim a legitimate victory continued to stick in my craw. By that point, I'd beaten just about every other series game, but because I'd never beaten Adventure, I couldn't claim to be a Castlevania master, which I felt was a real shortfall for me--for a guy who was a super-fan of the series and made a dedicated website in tribute to it. I needed to beat Adventure legitimately to earn that label.

So a few years later, sometime in early 2002, I popped Adventure into my Game Boy Advance and swore that this would be the day that I'd finally beat the Castlevania game that had been tormenting me since childhood! And the story played out in the same way that my stories with Zelda II, Mike Tyson's Punch-Out!! and Ninja Gaiden did: I exorcised long-lurking demons by eking out a victory after enduring a marathon session that brought me to the brink of emotional exhaustion.

I was so relieved when it was over. I did what I needed to do, and I was officially done. I never wanted to see Adventure again.

But I returned to it in the future. Over the next few years, I beat it a few times. And in recent years, I play through and beat it quite frequently--always without dying a single time. And as unbelievable as this might sound to you, I've actually become pretty fond of it. I honestly enjoy playing it!

Now, I maintain that Adventure, because its flaws are so damaging, is a substandard Castlevania game, but still I feel that it has some alluring qualities that make it worth checking out. It has sharp, striking visuals; immersive music; and a great sense of atmosphere; and it gives off a classic Castlevania vibe. There's fun to be had in looking at it and listening to it. It's just a shame that these positive aspects are so easily buried by the game's spiteful level design, indiscernible collision physics, and nagging performance issues.

So in recent years, Castlevania: The Adventure and I have reconciled most of our differences and created newer, more-happy memories, but still, when I think about Adventure, I'll always be reminded me of the lesson I learned when I played it back in my younger days: No matter how good you are, there will always be times in life when you disappointingly fall short of the mark and land flat on your face.

That's what both Konami and I did in our earlier days.

No comments:

Post a Comment