Whenever I reminisce about the days in which the NES was the most important thing in my life, there's inevitably a brief moment when I wonder about how much sweeter those days might have been had I made an effort to broaden my interests. Specifically, I feel regret for my having willingly ignored some of the NES' most popular games at the point in time when they were at their most relevant. I'm talkin' about the ones that would always appear in those "All the Greatest Hits Are Here!" magazine ads and promo inserts: Metal Gear, Wizards & Warriors, Blaster Master, Bionic Commando, Faxanadu, and the like--standout games that I never owned or played because I chose to dismiss each of their kind for one reason or another (usually for a dumb reason).

"I would have loved most of these games," I say to myself. "They would have done so much to positively shape my life."

Though, in every such moment, it tends to be that I'm most baffled by my younger self's decision to completely ignore 1989's Strider, which arrived to much fanfare. His choosing to avoid it makes little sense because it had everything he looked for in his games: It had a cool-sounding name, an interesting premise, and a strong focus on fast-paced action. Also, it was made by Capcom, creator of some of his all-time favorite games! How could he have overlooked it?

My only guess is "childhood idiocy."

Though, that wouldn't explain why I continued to avoid Strider in the decades that followed--why from 1989 to the mid-2010s, Strider and I remained worlds apart. I simply wouldn't go near it. There was never even an instance where I so much as sampled the game. Somehow, over the course of a twenty-year period, our paths just never crossed.

I mean, yeah--I'd heard a lot about Strider. I'd read about it in retrospectives. And I'd seen it in action a few times. I just never got around to playing it; I simply couldn't find the motivation to do so.

Well, that all changed a few years ago. After watching a couple of my favorite Youtube personalities play through Strider, all within the same period of time, and speak of it with such great fondness, I became intrigued by what it was said to offer. I felt inspired to make the experience my own. So one day during the following week, I cleared my schedule and spent a warm autumn evening with Strider for a play-through that was 25 years in the making. And that turned out to be the first of a number of play-throughs I completed over the next five years.

All that time, I was very eager to talk about my experiences with Strider, but I wasn't able to do so because I hadn't yet come up with a format that allowed for me to review games the way I desired to. But now that "Reflections," an ideal format, has come into existence, I finally have the opportunity I've long been waiting for. So now it's time for me to starting putting thoughts into words. It's time for me to talk about a game with which I have many issues, yes, but one that I nevertheless find to be strangely appealing.

Now, it's impossible to talk about Strider without first directing attention to its fundamental flaws and specifically the slew of technical issues that persistently exert their influence and do their damndest to negatively affect the game's every aspect--everything from its controls to its dialogue scenes.

Now, it's impossible to talk about Strider without first directing attention to its fundamental flaws and specifically the slew of technical issues that persistently exert their influence and do their damndest to negatively affect the game's every aspect--everything from its controls to its dialogue scenes.When, in the game's opening moments, you test out said controls, they appear to work just fine. Hiryu's movement and jumping controls feel tight and responsive. His jumps, which have a fixed vertical distance of four tiles and extend up to six tiles horizontally, can be easily modulated. His Cipher (the name of his sword) attack executes hastily and has no cooldown period, so he's able to unleash a successive slash at the precise moment the first slash's animation ends and essentially spam the attack; and because he can do this while moving forward and jumping, he has the ability to maintain constant motion and unabatedly tear through mobs of enemies as they pour in from offscreen. And it's also easy to execute his upward-facing Cipher attacks: Simply pushing up on the d-pad prompts Hiryu to to raise his Cipher into the air, and pressing the jump button while holding up on the d-pad causes him to perform a jumping up-thrust.

Moving, turning, jumping, crouching and attacking--in flat open spaces, like the one you occupy at the game's starting point, these actions prove to function reliably. Their accompanying animations can look a little jerky at times, sure, but still they execute quite smoothly.

But the moment you advance rightward and begin to interact with enemies and the surrounding environment, it all starts to go south; immediately the technical issues begin their intrusion. The first thing you'll notice is that enemy hitboxes are entirely inconsistent, and sometimes they simply cease to exist. For example: In one instance, you'll strike a foe from a one-tile distance and destroy him, as expected, but moments later, in an identical scenario, that same foe will somehow pass right through your sword and inflict contact damage! And because the designer neglected to program in invincibility frames, overlapping enemies can inflict damage at a rapid rate and sometimes zap away all of your health in an instant.

Hiryu's hitboxes, too, tend to be very spotty. There are times when he'll take damage from enemies or projectiles that are as many as 18 pixels away from the edge of his current hitbox! His up-thrust frames' hitboxes are especially inconstant; sometimes they're active and sometimes they're not, so half the time you can't avoid taking damage while you perform the move. This can become incredibly irritating when you're fighting a boss whose only weakness is the up-thrust; at any moment, you can be potentially punished with death for having the gall to strike the boss with the only attack to which he's susceptible.

So you're at risk every time you engage an enemy at close range. In such instances, all you can do is hope that your hitboxes remain somewhat constant.

Then there are the bevy of collision and processing issues, all of which work to prevent you from fluidly traversing and platforming across the game's environments. Most annoyingly, Hiryu's jumping momentum immediately halts whenever he makes contact with a wall or the side of an object; when this happens, he stutters momentarily and then meekly falls to the ground. So when you're attempting to jump up to a platform, you have to do what you can to avoid making contact with its edges, lest your momentum will die and your jump will be nullified. Hiryu stutters, also, when his jump hits up against a ceiling; this doesn't have any effect on the jump's momentum, no, but it looks really sloppy.

It's one thing after another: Dropped items appear one whole second after their bearers are killed, and they tremor for each second they're visible. As you travel upward, the screen continues to jump suddenly, in a choppy fashion, rather than smoothly scroll along. When you enter a room that contains an item or an NPC character, you have to wait two seconds for it to load in, and the action jarringly freezes while you wait for it to happen. And enemies spawn in not from the screen's edge but instead from one whole tile in, which works to significantly cut down on the amount of time you have to react to those who come charging in.

But the biggest offender, by a large margin, is Hiryu's wall jump move--the "Triangle Jump," which may very well be single most unreliable move in the history of video games. Most of the time, it just refuses to work, and I'm not sure why, exactly, that is. It's either that the frame window is incredibly small or the move is poorly coded. No matter what the cause is, it prevents you from being able to execute the move with any amount of consistency. So getting it to function as advertised is a total struggle, and when you do succeed in pulling off a Triangle Jump, you'll probably feel as though you only did so because you got lucky. When only a single Triangle Jump is required, it's a manageable situation because eventually you will get one to work, even if it's by accident; but when the situation is that you've fallen into a pit and you need to execute two or more successive Triangle Jumps to escape from it, forget it--you can be stuck there for several minutes if not forever. And there may come a point when you become so frustrated that you'll start to believe that simply resetting the game is a better option.

The only good thing I'll say about the Triangle Jump is that there aren't any instances where you have to use it to rebound between walls that surround bottomless pits.

And I'm not even going to comment on the collision issue that allows you to clip your way into walls and either bypass whole stage sections or zip your way over to stage areas to which you're not yet supposed to have access (including the final area, which speedrunners are able to reach in less than three minutes). No--I'll just shake my head and quickly move on.

But we do have to talk about the problems with the game's momentum physics.

Now, sure, it's pretty cool that a 1989 NES game contains something as advanced as "momentum physics"--that Strider's creators were eager to develop an in-game physics engine and hype it up as a big selling point--but the reality is that they just weren't implemented very well. They're sloppily coded and frequently produce unintended actions. It's supposed to be that Hiryu gains speed as he runs downhill and becomes capable of using that momentum to execute an extended horizontal jump. But it doesn't always work out that way. In many instances, he gets absolutely no extension on his jump; in others, the input is eaten and Hiryu never leaves the ground. This becomes a frustrating problem when you're required to long-jump your way across a lengthy gap or over a long bed of spikes; if, in such moments, the physics fail you, you may be forced to repeat whole sections or take heavy damage--probably enough to kill you.

Though, I'm happy to tell you that the physics' upslope coding is indeed sound. When you attempt to run upward on sloped surfaces, gravity absolutely works to slow down your movement. So points for that. I guess.

So yeah--Strider is a very unpolished game, and that's putting it kindly.

"So if everything you just told me is accurate, why the hell would I ever want to play this game?" you ask, understandably confused.

"So if everything you just told me is accurate, why the hell would I ever want to play this game?" you ask, understandably confused.Well, because, regardless of the fact that it suffers from a number of technical deficiencies, Strider still manages to be a pretty good game. Also, it has a lot of redeeming qualities.

What's most appealing about Strider is the novel twist it puts on the action genre. It eschews standard stage-by-stage progression and instead introduces a system of gameplay that has you continuously jumping back and forth between stage areas. You don't clear a stage and then permanently vacate it, no; rather, you travel to a stage area with the objective of meeting a small goal, like locating a certain individual or procuring a special item (a disk, a key, or an ability-granting piece of gear), and using the rewarded intel or power to gain increased accessibility--to gain entrance to other parts of the stage area or to a whole new stage area.

The stage-selection and info-analyzation processes are carried out from Strider headquarters and specifically from its Blue Dragon Console (a giant telescreen--something us enthusiast types always love to see in a game!). On this screen, you can analyze disks and extract from their stored video messages information about the locations in which your friends and enemies are operating and thus unlock new stage areas. Then you can transfer over to any of those locations.

Oh, and you can also request continue codes from the console. Whenever you do as much, though, you have to deal with the inconvenience of being returned to the title screen. But what's cool is that the game transitions you out with an informative "Coming next episode!" preview. It's a nice little touch; I always appreciate it when developers throw in cool little extras like that--when they put in an extra effort instead of settling for "good enough as is."

The mission takes us to locations all around the world, from Kazakh in Eastern Europe to regions in Egypt, Japan, China, Africa, Los Angeles and Australia. In general, stage areas are large, open and labyrinthine. Your mode of operation will be to explore to a stage in search of the most accessible pathways and therein, as mentioned, find a person or item that will help you to gain access to a new stage section or a new map location. Some special items can be found laying right out in the open while others only appear after you talk to a certain NPC character or defeat a boss (usually one of the six or seven bosses you repeatedly encounter). If you're unable to locate an item or an NPC character, you'll have no choice but to leave the stage area, which you can do by returning to its starting point and jumping while pushing up against the screen's left border; you can then transfer to a different location and try your luck there.

Along the way, you'll likely fall for some of Strider's tricks. There will be instances where you jump down into a floor opening, thinking that doing so is the key to advancing, and then watch on in horror as you drop all the way down to the area's earliest section. Likewise, you might enter into an important-looking transport tube thinking that it's going to carry you over to a special place only to have it deposit you back at the stage's starting point. It's true that not every floor opening and transport tube does this, but, still, you should exercise some suspicion when you see one--before blindly throwing yourself into it, you should first check around to see if there are any obvious entryways in the vicinity.

Stage areas aren't enormous, though, so this turns out to be only a minor annoyance. Getting back to where you were will never take longer than a minute.

Actually, Strider, on the whole, handles backtracking pretty well, which is to say that it does a good job of keeping it to a minimum. Really, it's only the visits to Kazakh that require you to backtrack to the starting point. Every other stage is nice enough to grant you instant exit after you meet one of its goals; it's either that (a) the game immediately sends you back to Strider headquarters or (b) a nearby transport tube carries you back to the stage's starting point, from which you can exit.

And still there's more to Strider. It contains a number of other systems.

And still there's more to Strider. It contains a number of other systems.The most important of these is its RPG leveling system, which controls the growth of Hiryu's health and energy meters. You gain levels when you meet certain goals (any of those mentioned previously), and each time you do, one or both of your meters' capacities increases. It's a little weird in how it works: For a while the meters are boosted in alternation, but later on they're boosted concurrently, and once you reach Level 6, the rewarded increase grows from 5 to an exponential number (10, 25, etc.). And this continues until you reach the Level 10 cap, at which point you'll have 150 health points and 100 energy points (way up from the respective starting amounts of 20 and 10).

The health meter's function is obvious: you get hit, you lose health; you lose all of your health, you die. Rather, it's the "energy" meter that might confuse you. "Wait--aren't 'health' and 'energy' the same exact thing?" you'll wonder at the start, thinking that the latter's inclusion is pointless.

Well, no--they're not so in Strider, which is so proudly nonconforming that it refuses to adhere to even basic naming conventions. No--in this game, the energy meter is essentially a "magic" meter that governs the use of "Tricks" (special abilities), which you learn as you gain levels. Along the way, you'll learn those like Fire, which allows you to toss fireballs; Medical, which replenishes 20 health points; and Jump, which increases your jump height. Each trick costs a specific amount of energy points; that number is listed next to the trick in the inventory screen, the place from which you activate these tricks. There are nine tricks in all; six of them are unique while three of them are advanced versions of existing tricks.

You maintain your meters by picking up dropped items, of which there are four: (1) Small health capsules, which replenish 1 health point. (2) Large health capsules, which replenish 10 health points. (3) Small attack energy, which replenishes 1 energy point. And (4) Large attack energy, which replenishes 10 energy points. You can prompt the appearances of such items by killing enemies and striking certain walls (there's never any indication as to whether or not a wall is hiding an item, so you might as well go ahead and strike any wall you come across; after all: spending a few seconds mashing a button is a small price to pay for a freebie).

And then there's the special gear that functions to increase your accessibility. Over the course of your mission, you'll pick up those like the Aqua Boots, which allow you to walk on water; the Magnet Boots, which allow you to walk along specially designated floors and ceilings (the ones that glow), Blaster Master-style; and the Attack Boots, which turn your sliding move into a sliding kick.

There are also two abilities that you learn independently of systems; you earn them simply by talking to certain people. The first is the aforementioned Slide In, a Mega Man 3-style slide move that allows you to squeeze into and slide through narrow passages; the slide is fast-moving, so you can also use it to speed your way through stages. The other ability is the Plasma Arrow, which allows you to fire a projectile from the Cipher; you do this by thrusting it upward for three seconds, until it charges up, and then pressing the attack button; and if you charge it for an additional second, you can release an even larger blast!

It's important that you seek out the Plasma Arrow (hint: it's in Japan; don't forget to fully explore that place) because you can't beat the game without it. And since the final stage, the Red Dragon, is a point of no return, you'll be screwed if you miss it. You won't be able to beat the penultimate boss, and consequently you'll have to restart the entire game. I have to admit: That's a pretty awful design choice; there's no good reason to lock the player in like that.

But that's the way it was back then: Developers would do anything they could to artificially extend the lives of their games. That was their way of forcing us to play them over and over again.

I'm not making excuses for that practice, no. I'm just telling you why they did it.

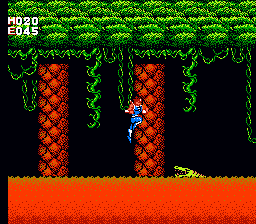

Strider isn't quite as visually striking as other late-80s Capcom classics like Bionic Commando, Mega Man 2 and DuckTales, no, but it's still a good-looking game. What's immediately noticeable is the breadth of its imagery. If there's anything consistent about Strider, it's that it's always displaying large, screen-filling backgrounds and textures that are both nicely rendered and visually interesting. All of the game's settings and structures are formed from such displays, each of which is rife with cool little environmental details (the lightning strikes that illuminate Kazakh's skies, the weapons and lockers seen in Kazakh's police department, the skulls that lay about Egypt's pyramid tomb, the demonic-looking samurai statues that stand in Japan's inner hall, and such).

Strider isn't quite as visually striking as other late-80s Capcom classics like Bionic Commando, Mega Man 2 and DuckTales, no, but it's still a good-looking game. What's immediately noticeable is the breadth of its imagery. If there's anything consistent about Strider, it's that it's always displaying large, screen-filling backgrounds and textures that are both nicely rendered and visually interesting. All of the game's settings and structures are formed from such displays, each of which is rife with cool little environmental details (the lightning strikes that illuminate Kazakh's skies, the weapons and lockers seen in Kazakh's police department, the skulls that lay about Egypt's pyramid tomb, the demonic-looking samurai statues that stand in Japan's inner hall, and such).The game is bursting with imagery--the type that does a great job of simultaneously communicating to you exactly where you are and conveying to you the atmosphere of said location. For instance: As you traverse Kazakh's exterior, you'll observe the lightning strikes, the eerily desolate city backdrop, and the cold steel construction of the walkways and quickly become aware that you've arrived as the base of operations of an oppressive regime whose tyrannical rule has cast a cloud of bleakness over the country. (This is one of my favorite video-game settings because I'm a sucker for opening stages in which storms rage over desolate environments. This one has such great atmosphere to it. I love everything about what it does.)

And you'll be told similar stories as you run through Egypt, Japan, China and the rest. You'll instantly know the type of location at which you've arrived and what the situation is--if the area is besieged, barren, or in a state of ruin.

The only problem is that sometimes it can be difficult to take in and gain an appreciation for these visuals because the constant technical issues--the camera's jerky movement, the enemy pop-in, the stuttering, and the sprite-flickering--work to prevent you from doing so. All of the graphical glitching can be highly distracting and jarring to where you'd rather save yourself the eyestrain and just focus on the action. It doesn't completely ruin the game's visual-communication aspect, no, but it definitely detracts from it.

Character design and animation, however, are a mixed bag. Character are rendered quite nicely--they're large and detailed and animate over several frames--but some of the time they appear to be tremoring as they move about. I don't know if this is a conscious design decision or if it's the case that this aspect of the game is simply another victim of the game's technical deficiencies. Whatever the case, it just looks bad.

Character design and animation, however, are a mixed bag. Character are rendered quite nicely--they're large and detailed and animate over several frames--but some of the time they appear to be tremoring as they move about. I don't know if this is a conscious design decision or if it's the case that this aspect of the game is simply another victim of the game's technical deficiencies. Whatever the case, it just looks bad.Also, Hiryu's running animation is pretty stilted-looking. When he's in a running motion, his lower half bends at a weird angle while his his torso remains upright (clearly because the running animation uses the idle Hiryu's upper-body sprite-set), and he appears to be gently high-stepping as one would do if the ground were on fire. It's kinda awkward-looking.

You can always count on Capcom to deliver a great soundtrack, and that's exactly what you get here. Strider's is a collection of adrenaline-infused, highly electric 8-bit tunes--pure late-80s video-game music with all of the expected trappings: lively metal strains, heavy percussion, and a vibe that's able to evoke instant nostalgia.

You can always count on Capcom to deliver a great soundtrack, and that's exactly what you get here. Strider's is a collection of adrenaline-infused, highly electric 8-bit tunes--pure late-80s video-game music with all of the expected trappings: lively metal strains, heavy percussion, and a vibe that's able to evoke instant nostalgia.What's most notable about Strider's music, though, is that it does a terrific job of conveying the tone of the game's world. Its despondence-imbued tunes speak of a futuristic dystopian setting and help to the describe the atmosphere of such a place. More so than the visuals, they're able to explain to you both the mood and the condition of the environment you're currently traversing. When you listen to, say, Egypt's pyramid theme, you'll be informed that said pyramids are haunted by its captors' barbarous spirit and have thus fallen into a state of deep neglect. And every other tune, from the Strider headquarters theme to the piece that plays during the credits, tells a similarly intriguing story.

It's classic Capcom-sounding music doing what it's apt to do, and the result of that influence is another great 8-bit soundtrack.

And, really, any game whose inventory screen has its own exclusive theme is tops with me!

Strider's sound design, in general, is solid. Basic operations emit appropriately futuristic-sounding bleeps and whizzes, and the game's attacks, explosions and mechanized noises are all convincing-sounding.

It's tough to accurately rank Strider's difficulty-level. Ostensibly it's a moderately challenging game. It beats you up at times, yeah, but then it also does a lot to keep you alive: Enemies are constantly dropping health capsules--mostly the larger type--and the Medical ability, which you learn fairly early on, provides considerable replenishment (20 health points) for a surprisingly low cost (10 energy points). Bosses will give you trouble at first, sure, but you'll be able to take them out easily once you discover their weaknesses. Hell--some of the boss battles are so stupidly easy (like the one against Kain, who dies instantly when you deliver a single strike to his back) that you may not even realize that they were boss battles.

It's tough to accurately rank Strider's difficulty-level. Ostensibly it's a moderately challenging game. It beats you up at times, yeah, but then it also does a lot to keep you alive: Enemies are constantly dropping health capsules--mostly the larger type--and the Medical ability, which you learn fairly early on, provides considerable replenishment (20 health points) for a surprisingly low cost (10 energy points). Bosses will give you trouble at first, sure, but you'll be able to take them out easily once you discover their weaknesses. Hell--some of the boss battles are so stupidly easy (like the one against Kain, who dies instantly when you deliver a single strike to his back) that you may not even realize that they were boss battles.Also, you have unlimited continues, and there's no real punishment for dying. When you select "Continue" from the title screen, you'll promptly return to action with all of your items and abilities on hand.

From a mechanical perspective, the game treats you pretty well. It gives you everything you need to overcome its challenges. It says, "See? I'm quite beatable!"

But then there's the aspect that delivers the opposite message: the technical issues, from which Strider's true difficulty is derived. They're what upgrade the game from "moderately challenging" to "pretty damn challenging." They're what serve as a constant threat. The poorly coded collision-detection often functions to nullify your jumps and cause you to fall into gaps and get stuck on the spikes over which you're attempting to hurdle. It's almost impossible to consistently execute Triangle Jumps, and an inability to do so causes frustration and invites scenarios in which you can become permanently stuck. You continuously collide with enemies that pop in from seemingly nowhere. And direct contact with enemies is always draining your health down to nothing.

Strider's challenge isn't a question of whether or not you can beat the alien-lookin' "tree" boss with low health but rather if you'll be able to land firmly on the moving platform instead of clipping through its edge or being pushed off of it, into a long gap, by an unseen force. It's all about whether or not you can clear that four-tile-wide spike pit in Australia's opening section, which should be easy to do, because jumping that far is well within Hiryu's capabilities, but isn't because of the spotty collision-detection. "Sorry," it'll say, "when you landed, your boot was only six pixels above the platform instead of the eight pixels I deemed necessary at this very moment, so into the pit you go!" (And good luck getting out of it!)

So let's just say that Strider can be difficult for the wrong reasons--due to aspects that weren't intended to impact the game's challenges.

Strider is one of those games that I've been able to play and enjoy without knowing much about its story or the universe of which it's a part. It's not that I haven't been trying to understand the game's plot, no; it's that the localization is so rough that I'm never able to get a clear sense of who the characters are or what, exactly, any of them are talking about. For the longest time, I was under the impression that it was a game about a guy named "Strider" who works for a world-police organization that has grown so corrupt that he has no choice but to start rooting out the bad actors--find them wherever they're hiding and eliminate them.

Strider is one of those games that I've been able to play and enjoy without knowing much about its story or the universe of which it's a part. It's not that I haven't been trying to understand the game's plot, no; it's that the localization is so rough that I'm never able to get a clear sense of who the characters are or what, exactly, any of them are talking about. For the longest time, I was under the impression that it was a game about a guy named "Strider" who works for a world-police organization that has grown so corrupt that he has no choice but to start rooting out the bad actors--find them wherever they're hiding and eliminate them.It wasn't until fairly recently that I sought out and read through the manual and gained a base understanding of the game's story. The gist is that "Strider" is the name of an elite "secret maneuvers group" that engages in all kinds of illegal activities. It specializes, the manual tells us, in smuggling, kidnapping, demolitions, disruption, and such. Hiryu used to be a part of this group but left after having a crisis of conscience; he decided to retire and find a peaceful life in Mongolia. However, he finds himself back with the group after being told by its Vice-Director, Matic, that his friend and fellow Strider Kain has been captured by an enemy force. Matic orders Hiryu to find and destroy Kain, since the enemy knows of its captive's identity and may attempt to extract from him information about Strider's activities, or face a severe consequence: the slaughtering of the Mongolian people. So Hiryu has no choice but to return to action.

Now, even knowing all of that, I still have no clue as to who any of the in-game characters are or what anyone is trying to communicate. The dialogue is so poorly translated that I can't tell who is friend or foe or what, exactly, I'm accomplishing in each country. My only guess is that the scientist-lookin' chaps are the good guys, and the ones in military fatigues are the rogue Striders who we're trying to eliminate. Except they're all bad because they work for a group that likes to engage in smuggling and kidnapping. And all of this has something to do with an evil tree that wants to rule the world.

Well, maybe.

The only thing I know about in-game events is what the manual mentions: After Hiryu rescues Kain, he discovers that Strider is working with an organization called "Enterprise" to put into play an evil project called "Zain." Hiryu then comes to the conclusion that the only way out of his predicament is to destroy Zain (which is described to be a "mind-control weapon") along with Enterprise and Strider.

So now the fate of the world hangs in the balance.

Or something.

Up until about, say, early 2000, I wasn't even aware that Strider was a conversion of an arcade game; somehow I never came across the original in arcades, so, as per usual, I simply assumed that "Strider" was another NES-exclusive property. This was a theme with me when it came to Capcom's arcade games; there were a bunch of them I simply never encountered (see Trojan and Bionic Commando). It's either that I was amazingly unobservant or, as I've theorized in past pieces, Brooklyn arcade-owners hated the company.

Up until about, say, early 2000, I wasn't even aware that Strider was a conversion of an arcade game; somehow I never came across the original in arcades, so, as per usual, I simply assumed that "Strider" was another NES-exclusive property. This was a theme with me when it came to Capcom's arcade games; there were a bunch of them I simply never encountered (see Trojan and Bionic Commando). It's either that I was amazingly unobservant or, as I've theorized in past pieces, Brooklyn arcade-owners hated the company.In truth, I currently know very little about the arcade original or the other series games, so there's nothing I can really say about them. Though, in the near future, I am going to make it a point to seek them out and learn as much about them as I can. Naturally I'm going to start with the original work because, as I always say, "Whenever you're planning to get into a series, you should always start with 'Part 1.'"

And, if I feel so inspired, I'll write about my experiences here!

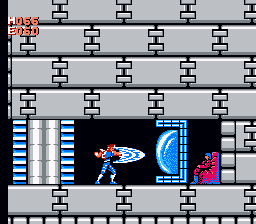

Oh, and big points to Strider for including a scene in which you fight a boss (Kain) in the Blue Dragon Console telescreen room! As I expressed in my Rolling Thunder piece: I always love it when such a thing occurs in a video game--when the action suddenly spills into a location that previously appeared on its title screen or in a cut-scene; a location that was assumed to be part of a separately-existing graphical asset and thus completely off-limits to the player.

Oh, and big points to Strider for including a scene in which you fight a boss (Kain) in the Blue Dragon Console telescreen room! As I expressed in my Rolling Thunder piece: I always love it when such a thing occurs in a video game--when the action suddenly spills into a location that previously appeared on its title screen or in a cut-scene; a location that was assumed to be part of a separately-existing graphical asset and thus completely off-limits to the player.I can't explain to you why, exactly, I love it, no. I just know that I do.

I'm sure that a lot of you do, too.

Closing Thoughts

And that's the story with Strider--a game that's considerably flawed, yes, but nonetheless engaging in a number of ways. There are times when playing it can become an exercise in frustration--instances when the technical issues can work to seriously inhibit your ability to make simple jumps or avoid making contact with even the tiniest projectiles--sure, but then there are plenty of stretches when it persists in being a playable, enjoyable action game.

And that's the story with Strider--a game that's considerably flawed, yes, but nonetheless engaging in a number of ways. There are times when playing it can become an exercise in frustration--instances when the technical issues can work to seriously inhibit your ability to make simple jumps or avoid making contact with even the tiniest projectiles--sure, but then there are plenty of stretches when it persists in being a playable, enjoyable action game.And if those moments, on their own, aren't enough to help Strider overcome its flaws, then it can always rely on those "redeeming qualities" to provide the extra compensatory muscle. And it has, as I've detailed, quite a few such qualities: Its jump-between-stages style of progression is a novel one. Its settings are visually interesting. Its graphics and music do wonderfully to convey tone and atmosphere--to define Strider's dystopic world and describe the nature of the environments that comprise it. And it's short enough to where it doesn't wear out its welcome; it makes its point quickly and in doing so provides you just the fill you need: an hour of solid action.

Now, is all of that actually enough to help Strider overcome its the game's slew of technical issues? It's tough to say. Really, it depends on how you think about old video games--about what is and isn't important to you.

Now, is all of that actually enough to help Strider overcome its the game's slew of technical issues? It's tough to say. Really, it depends on how you think about old video games--about what is and isn't important to you.To someone like me, who gives a lot of importance to how a game makes you feel, the intangible elements (like that "conveyance of tone and atmosphere" stuff I'm always going on about) can mean a whole lot; emanations that evoke wonder or stir the imagination can do a lot to disguise flaws and therein work to elevate a middling or mediocre game to "OK" status.

That's what happens in the case of Strider: I can't help but be enchanted by the nostalgic vibe it gives off. It's highly intoxicating. And when I fall under that influence, my critical-thinking ability quickly fades away, and suddenly I'm not as eager to notice or point out the game's flaws. And so a considerably defective game somehow comes to qualify as a "pretty good" one.

So here's my recommendation: If you're like me and consider "evocation" and "nostalgia-inducement" to be important qualities in your games, then certainly you should give Strider a look; those qualities, with which its rich, will help to mask its deficiencies and evoke feelings of delight. Though, if you don't care about such things, then you'll probably want to stay away from Strider--avoid a game that's likely to be the source of a whole lot of irritation.

I put Strider in the class of Rygar. As I see it, its shortcomings are a product not of bad design but of a development team's ambition outweighing the NES' actual capabilities. If, as you're playing through Strider, you take the time to observe it, you'll surely come to sense that Capcom really wanted this game to be something special; it's just that, unfortunately, the current level of technology was insufficient, and so the developers weren't able to properly execute their vision. Still, their ambitious spirit pervades the game. You can see it. You can feel it.

I put Strider in the class of Rygar. As I see it, its shortcomings are a product not of bad design but of a development team's ambition outweighing the NES' actual capabilities. If, as you're playing through Strider, you take the time to observe it, you'll surely come to sense that Capcom really wanted this game to be something special; it's just that, unfortunately, the current level of technology was insufficient, and so the developers weren't able to properly execute their vision. Still, their ambitious spirit pervades the game. You can see it. You can feel it.So yeah--I tend to have a soft spot for games that exude such a quality. I always appreciate it when a team of developers puts forth an ambitious effort, even if the result of that effort is a buggy mess of game. I give them something of a pass.

Really, I always find it fun to catch up on the games I missed back in the 80s. As I play through them, I find enjoyment in thinking about what they might have meant to my younger self and his circle of friends. "Would Strider have become one of our go-to action games?" I wonder. "And how, if at all, would it have shaped our group's gaming culture?"

Really, I always find it fun to catch up on the games I missed back in the 80s. As I play through them, I find enjoyment in thinking about what they might have meant to my younger self and his circle of friends. "Would Strider have become one of our go-to action games?" I wonder. "And how, if at all, would it have shaped our group's gaming culture?"Sadly, I'll never know the answers to those questions.

I can say for certain, though, that Strider will be a part of my life going forward. And when 30 years from now I look back on the games that made Phase 2 of my NES-playing life an amazing time of discovery, it'll surely be that Strider is included in that group.

No comments:

Post a Comment