As I hurried along the well-traveled path that led directly to Toys R Us' good ol' game aisle, I was single-minded in my objective. My thoughts were focused entirely on the task at hand, and thus there was no chance that they could ever be tainted by silly ideas like "careful consideration" and "reasoned decision-making."

And that, I understand now, is the reason why I failed to recognize that my plan to purchase Mega Man III, the series' latest Game Boy entry, was being influenced not by a genuine desire to experience the Blue Bomber's latest adventure but rather by the worsening illness that was inflicting me at the time.

Had the appropriate branch of medicine existed at the time, its specialists might have been able to identify the illness' cause and explain to me why, exactly, I was behaving this way. They might have been able to tell me why I was feeling obligated to buy sequels even though I was completely fatigued on them. And then I might have seen the error of my ways and saved a lot of money.

Hindsight, instead, was my teacher. It helped me realize that I had been corrupted by "the sickness"--that the subversive forces of marketing had clouded my judgment and rendered me unable to resist the seductive advances that were being made by companies like Capcom, which had become adept at saturating video-game media with information and imagery that was designed to convince unsuspecting players that they'd be missing out on special experiences if they failed to keep up with and buy the latest releases.

It was that insidious influence that made me decide that I needed Mega Man III to be a part of my life even though I feared that it would be a pedestrian, forgettable series entry.

And by 1993, I was sick of that practice. I was sick of rehashed sequels in general. I wanted developers to take chances and create sequels that tried new things.

And I didn't think that it was crazy for me expect Capcom to finally deliver a Mega Man sequel that meaningfully evolved the series' formula. "Get creative and show some real ambition," I begged the company. "Give me something new like a reimagined style of level design or a revolutionary game mechanic."

I was betting, though, that the recently announced Mega Man III would likely feature neither of those things. "There's no way that current Capcom is going to take any chances," I thought, "especially with a lower-budget portable game."

Early previews of Mega Man III were vague enough to where I couldn't be certain of that assumption, sure, but still the company's recent track record was enough to convince me that I was correct in my thinking. I didn't have to look any further than the proximate releases of Mega Mans 4 and 5 for proof that the company was now stuck in a mode and unlikely to take any significant creative risks with its prized franchise.

So I wasn't shocked when Nintendo Power Volume 44's full-length Mega Man III preview plainly stated that the formula for Capcom's latest was exactly what I was expecting it to be: The game's starting cast was comprised of the remaining four Robot Masters from Mega Man 3; there was an intermediate stage that was home to a Mega Man Killer; the other four Robot Masters were from Mega Man 4, and their habitats, of course, comprised a Wily ground fortress; and after you cleared out the ground fortress, you chased Wily into space and entered into his ocean fortress.

The game was a pure copy-and-paste job, and that didn't surprise me at all.

I couldn't muster even a tiny bit of excitement over what I was seeing and reading, but at the same time, I remained honest with myself and refrained from going on that same old performative rant about how the game was skippable because it was more of the same. I knew, after all, that I was going to run out and buy Mega Man III as soon as possible regardless of how uninterested I was in playing it.

And that's what I did: Sometime in January of 1993, I went over to the Toys R Us over at Caesar's Bay Bazaar and bought myself a copy of Mega Man III (using some of my Christmas money, of course). Then I brought it home and started playing it.

I played it safe at first and started with Snake Man's stage because, well, his was the one with which I always started when I played NES Mega Man 3. I had a strong understanding of his pattern, and I was certain that I could easily take him out with just the Mega Buster.

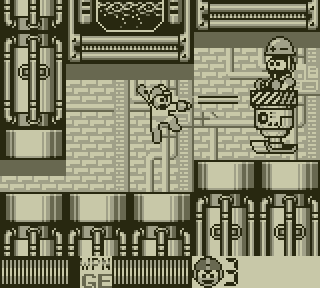

And as I started traversing the stage, I could tell, right away, that Mega Man III was a pretty ambitious Game Boy game. It was on the next level visually and aurally, and clearly it looked and sounded much better than its predecessors. "This is some high-quality work," I thought to myself as I observed the graphics and listened to the music.

And as I continued on and played through the subsequent stages (following the weakness chain that I knew so well, naturally), I gained even more appreciation for the game's visuals, in particular, and made note of the fact that they were so impressive that they actually compared very favorably to the NES games'! They even topped the NES games' visuals in some areas!

That's how good Mega Man III looked.

I mean, the game lacked color, yeah, but still it was visually superior to the NES games in some notable ways: Its sprites and textures were sharper and more-detailed; and its stages' backgrounds were filled with cool, unique graphical elements like patches of animated palm trees, pulsating vegetation, electrical flashes, and glowing spinal columns, all of which helped the stages to differentiate themselves from their NES counterparts and establish their own personalities.

And I was happy about that. I was glad to see that Mega Man III was given a degree of ownership over the material.

The game's composer abandoned the idea of creating distinctive tunes for each Robot Master stage and chose to instead revert back to the practice of re-sampling tunes from the NES games, and that struck me as odd because I was sure that Mega Man II's effort to mix things up musically was the start of a trend. "Obviously Capcom is going to start using original soundtracks to differentiate the Game Boy games from the NES games," I thought.

And that's what I was hoping the company would do with Mega Man III's soundtrack. I was looking forward to hearing some newly composed tunes and taking some time to think about the unique stories they were telling.

So I was a bit disappointed when I started Snake Man's stage and learned that the game was instead using arranged versions of the familiar NES stage themes. "We're back to using the NES tunes?" I lamentably questioned. "That's an unfortunate reversal of what Mega Man II was working toward."

But I didn't consider the composer's approach to be a completely regressive development, no. I couldn't do that because the arranged tunes were amazingly great! The composer did an outstanding job of recreating the classic themes and jazzing them up and making them livelier and more spirited, and thus he or she made a very compelling case for their return!

I was so impressed with the effort, in fact, that I no longer cared to complain about the lack of uniquely composed music! "I'm fine with this," I thought to myself. "I like these arrangements also as much as the ones in Dr. Wily's Revenge. They're a great part of the package!"

My favorite tune, actually, was one of the soundtrack's unique compositions: the piece that played in Wily's ocean fortress. I was fond of it because it was a powerfully moving piece and because it was able to evoke all kinds of strong feelings. It was an emotionally complex tune whose combination of upbeat and melancholic tones worked together to create a reflective atmosphere and inspire me to think deeply about the events that led up this point: my battles with the eight Robot Masters and Punk; my previous struggles with Wily and his Mega Man Killers; and all of the Mega Man adventures I'd been on since 1988.

And it spurred me, also, to derive inspiration and determination from those memories and use their energy to fuel my push to the finish. "The end is near," it said to me, "so it's time to resolutely charge forward and begin steeling yourself for the final battle."

The tune looped over and over again as I traversed that lengthy final stage, and as it did, it created a pervasive air of culmination and emotional resonance that was powerful enough to convince me that I was moments away from experiencing a climactic grand finale. "This is it," I thought. "This is going to be the battle that ends the original series in epic fashion and provides it some meaningful closure!" (Ending the series here was never Capcom's intention, it turned out, so in time, I came to interpret this tune in a different way. I began to regard it more as a nostalgic ballad that beautifully told the story of my history with the series and perfectly encapsulated what the Mega Man games meant to me emotionally.)

It truly was one of the best, most impactful tunes in series history.

Unfortunately, Capcom's ambition to make Mega Man III one of the Game Boy's most visually and aurally impressive games created some considerable drawbacks. To start, the game was plagued with slowdown, and there were times when the traversal of extended stage sections was occurring in what was essentially bullet time. The aging, technologically deficient Game Boy simply couldn't do what the designers were asking it to do: simultaneously render three-plus character sprites, multiple collisions, and a number of background and sprite-layer animations and do so while generating four-channels'-worth of high-quality sound.

And the result was a game that was moving in slow motion the majority of the time.

Most annoyingly, the processing issues were compromising the game's ability to read control inputs. There were numerous instances in which I took damage or died because the game ate my jumping, shooting or sliding input and left me standing in an idle position and vulnerable to attack. And that just wasn't acceptable.

What helped to magnify the game's inadequacies were the level designers' sinister tendencies. I was only two or three stages into the game before it became painfully clear to me that it was far more difficult than its immediate predecessor, Mega Man II (whose difficulty was comparable to NES Mega Man 2's), and that its frequently cruel level design was to blame for that.

More so than they did in the previous games, the level designers liked to use the Game Boy's cramped screen dimensions against the player. They had a particular fondness for those awful close-quarter jumps that you could only clear by standing on platforms' extreme edges and executing horizontal jumps while trying not to bonk your head on overhanging ceilings. These types of jumps were everywhere. The worst of stages were littered with them!

They also loved to hit you with cheap surprises like blind drops into rooms whose surfaces were covered in spikes and enemies spawning in right at the screen's edge, obnoxiously, and colliding with you as you were in mid-jump and consequently knocking you into death pits. They used such tricks in abundance.

Additionally they had a thing for spiky obstacles and used them to a maddening degree in a couple of stages--particularly in Dust Man's stage, whose corridors were loaded with spiky surfaces and expansive spike pits and, naturally, many in the way of close-quarter jumps and dangerous three-tile-long gaps. "This is absolutely insane," I kept thinking to myself as I traversed and re-traversed his grueling stage.

I was angry at the game before, but Dust Man's stage was the point in which I really started to get pissed off.

Later on, I almost lost it during my 15th or 20th attempt to clear Dive Man's hellish stage. It was by far the worst of them. Almost all of it surfaces were comprised of spikes, and you had to continuously execute pixel-perfect jumps to get around and over them. Toward the stage's end, there was a particularly nasty segment in which spike pillars and oscillating spike-lined platforms were placed everywhere, and you had to somehow negotiate your way around them while dealing with explosive mines and the irritating robotic manta rays ("mantans," as they're called), which were constantly swimming in at awkward angles.

That segment broke me and left me feeling demoralized.

Dive Man's stage was simply nightmarish. I feared it more than any other. Whenever I was playing Mega Man III, I'd always be thinking ahead to his stage and dreading the thought of having to traverse it.

And I could tell that the designers were well aware of their cruel tendencies. They weren't handing out energy tanks like lollipops because they were nice people, no. They were doing it, obviously, because they knew that the player would need an abundance energy tanks to compensate for all of their questionable design choices: the insane enemy rate, the ridiculously high damage ratios, and the creation of punishing bosses like Little Suzy--a giant octopus battery that inflicted a crippling amount of damage and repeatedly triggered a screen-shaking effect that caused the game to eat control inputs.

It was their way of apologizing for what they'd done.

My encounter with Punk, in particular, typified my experience: I found him to be a creative, memorable foe, but the whole time I was engaging him, I was thinking more about the fight's design qualities and how twisted it was to place a large, speedy boss in the tiniest of rooms (his attacks and movements had to have been conceived with NES-type screen dimensions in mind, I felt).

I mean, I had good reflexes and all, but still, there was just no way that I could reliably read the movements of a character whose dash and projectile attacks were being launched from a mere six inches away and at speeds of 50 miles per hour. I wasn't that fast.

My reflexes sharpened over time, sure, but the game's input-reading ability didn't, so even when I was fast enough to dodge Punk's attacks, I still had trouble with the fight because I couldn't always get Mega Man to do what I needed him to do. In those instances, I had to rely on luck and hope that Punk's attacks would just happen to miss.

And the only conclusion that I could draw was that Mega Man III wasn't a game that was meant to "beaten." It was, rather, something that was designed to be endured. That's how I felt as I watched the game's ending. "I didn't actually 'achieve victory,' no," I thought to myself. "All I did, really, was just happen to survive a series of crazy trials."

And after I finished my second or third play-through of the game, I was pretty much done with it. At that point, I determined that it was simply too frustrating to be enjoyable. Then I proceeded to avoid it for almost eight years. "Why would I want to play Mega Man III and be frequently driven to anger," I'd ask myself whenever I was hungry for some Game Boy Mega Man action, "when I can instead play the reliably fun Mega Man II and have a guaranteed positive experience?"

It was an easy choice.

When I returned to Mega Man III via emulation sometime in 2000 (which I did solely for the purpose of gathering information for my ill-fated Mega Man site), I had a much different experience with it. I discovered that it wasn't as brutally tough as I originally thought, and I was actually having fun with it the majority of the time. Its level design wasn't quite as cruel as I remembered it being, and suddenly I found myself embracing a lot of what it was doing. "This is a very good game," I thought.

I felt the same way about Mega Mans IV and V when I finally replayed them.

What happened, hindsight tells me, was that I had grown to appreciate these games for the way in which they promoted gaming's classic values, which had sadly been forgotten, and for how their nostalgic vibes and emanations reminded me of a time when two of my greatest loves in the whole world were Mega Man and the Game Boy. I now regarded them as wielders of a special power: the ability to temporarily transport me back to a place that I sorely missed and allow me to spend some quality time there.

And that, specifically, was the reason why I was suddenly eager to embrace them. It's why I continue to be so fond of them in the current day.

Because the fact, as time has shown me, is that these games are the last of their kind. They're the last vestige of an era in which the Blue Bomber was such a force that his series could demand yearly installments on two separate platforms. That he no longer holds that type of power is the reason why I'm now more inclined to cherish his games and overlook their shortcomings. And it's why I'm willing to forgive my past self for being such a compulsive sequel hound.

Considering how things turned out, I'm glad that I decided to purchase all of the Mega Man Game Boy games and make them a part of my history.

As I do for the post-Mega Man 3 NES entries, I place Mega Man III and its follow-ups in a special class of games whose meaning has changed to me over time. To my younger self, they represented stagnation and laziness. They were tired retreads that conveyed to me that the original Mega Man series was content to be merely what it was and never anything bolder or grander.

But to the 2015 version of me, who has watched the world change dramatically over the course of two decades and five hardware generations and now fears that the medium's history is perilously close to being tossed away like a diseased albatross, they're something much different. They're strong symbols of the types of games that I could never stand to lose.

Here's to hoping that they live forever.

Yeah, I agree that the difficulty of Gameboy Mega Man III was pretty brutal (moniker-wise, I would have liked it if Capcom had used the Japanese "World" sub-title in America too, to differentiate it more from the NES releases), but I prefer that to the insulting cake walk that was Mega Man II (I beat that one in two hours, tops, after opening the box--it's too bad that it didn't have a "Hard" mode like the NES version, as that would have given it more replay value--I wonder if there's a Game Genie code to double the damage enemies do?) Dust Man's stage is the one I really dread in MM3; I particularly hate those rising/lowering sections of blocks that you have to navigate through. It has never occurred to me that the frame rate/slowdown during the Giant Suzy battle could be the reason for my control pad/button inputs not reading, I just assumed that the shockwaves from the cyclopean machine's landings were doing that and it was an intentional gameplay mechanic of the battle (similar to how large bosses in other games can stun/interrupt you if you're on the ground when they land/stomp on terra firma).

ReplyDeleteOh, Suzy's screen-rattling eating the player's input is surely intentional, but what makes it worse is that the battle is also plagued by unintentional (I think) frame-rate issues. It's emblematic of how the latter three Game Boy titles disregard system limitations in the name of ambitious graphical design.

DeleteSolid games, though.