As I've said numerous times in the past: In my younger days, I struggled to see the appeal of movie-based video games. Whereas other kids excitedly wondered about the apparent potential of games that allowed you to experience movies in interactive form and take control of onscreen heroes like Rambo, Alan "Dutch" Schafer and Robocop, I could barely keep myself from drowning in apathy whenever I thought about the idea of the two mediums crossing over in some way.

I was averse to the idea because I felt that the movie and video-game mediums were completely incompatible with one another. Each possessed its own unique values and produced works that were designed to be consumed in a very specific way, and thus any attempt to adapt a movie to video-game form or vice versa would invariably result in the creation of a product that was so dramatically different from the original work that it would badly misrepresent it. It would result in a game or a movie that was bereft of property's most important values and consequently unappealing.

That was my view.

I was particularly down on movie-to-game adaptations. I just didn't believe that it was possible to derive compelling interactive experiences from a medium whose most important values included tight scripting, character and plot development, and an emphasis on dialogue. If you tried to do it, you wound up with either a boring story-based game or a game whose attempt to incorporate elements from a movie resulted in a platformer in which you traversed generic, uninteresting settings and went around punching or stomping mundane enemies like parking attendants, beggars and store clerks.

Nothing good came from mixing these two mediums together.

That was the first thought that popped into my head when I learned that a video-game adaptation of 1989's Batman was coming to the NES. "This isn't going to work," I immediately determined. "You're not going to make a good action game out of a movie whose version of Batman hides in the shadows and emerges only occasionally to punch a low-level goon in the face."

I was as big a fan as any of Tim Burton's strikingly stylistic Batman revival, but I simply didn't have any interest in playing a game that was based on it. I was so cold on the idea, in fact, that I couldn't even be inspired to read a preview or look at a single screenshot. I saw no appeal in such a game.

Also, I was rightfully wary of licensed products. They were usually substandard. And that was another reason why I didn't feel bad about instantly dismissing Batman: The Video Game. "This game will no doubt be your typical licensed junk," I was certain. "It'll probably be a game in which Batman runs around punching out stray dogs and murdering birds with his gadgets."

I knew, based on my knowledge of gaming history, that the game's production was likely headed in a bad direction, and thus I had no interest in following its progress and seeing how it turned out.

Fortunately for me, though, there was an antidote to my willing ignorance: my brother, James, who was always inclined to give a game a fair chance and avoid being influenced by preconceived notions. He had an adventurous spirit, and oftentimes his open-mindedness was a benefit to me because it helped me to discover great games that I either didn't know about or was predisposed to overlook.

For most of my childhood, there was a common scene: James would emerge from his basement domain and walk over to the den with an unfamiliar-looking game in his hands, and he'd enthusiastically present it to me and do so with the intention of inspiring an equally exuberant response. Then I'd play the game in question and wind up liking or loving it.

And on a random day in early 1990, the scene repeated: James emerged from the basement with Sunsoft's Batman in his hands, and then he rushed over to the den and excitedly presented to me!

But on this occasion, though, the conditions were a bit different. This time, I was familiar with the game that he was holding. I knew what it was because I recognized the symbol on its packaging: It was the unmistakable Batman insignia.

"Oh no--it's that game!" I thought to myself when I saw the symbol.

But because I didn't want to hurt James' feelings, I feigned a smile and acted as though I was eager to play the game. Then, to finish creating the illusion, I ran up to my room, where my NES was stationed, and popped the game into the console. "For James' sake," I thought, "I'll spend about ten to fifteen minutes with the game and then pretend that I had a good time with it. That should be enough to convince him."

But then something unexpected happened: In its earliest moments, Batman managed to pique my interest. It did so because its presentation reminded me of Ninja Gaiden's. It, too, used cinematic cut-scenes to establish stage settings and advance the story, which I felt was an intriguing approach. "This is honestly a brilliant way to insert elements from the movie and have them enhance the action and the gameplay rather than intrude on them," I thought. "This should be the template for all movie-to-game adaptations!"

The designers came up with a fine solution to the problem of incompatibility: keep the film elements condensed and separate, and position them merely as the backdrops to the action scenes, which will remain purely the creation of the game, itself. And I was happy to admit that their idea was a great one.

I was fond, also, of Batman's nifty wall-jump move, which was pretty similar to Ryu Hayabusa's (and thus it created another interesting connection between the two games). It wasn't as smooth or as maneuverable as Ryu's version of the move, since it was designed to be used in a more-tactical manner, but still it looked really cool and was fun to use.

So my first impressions of the game were very positive.

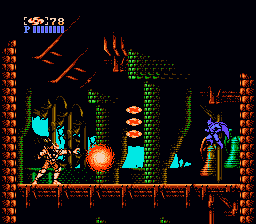

Batman, in great contrast to what I was expecting, had an instantly perceptible air of quality to it (which I probably would have anticipated had I been familiar with developer SunSoft's previous works). It impressed in a number of ways: It looked terrific (I didn't mind the fact that Batman's suit was, for whatever reason, colored purple rather than black or blue), it had a striking amount of gameplay depth, and it boasted a lot in the way of well-schemed, engaging level design.

And then there was the best part of the package: the music, which I found to be outstanding! It was way better than any movie-based-game's music had any right to be!

The game's opening-stage theme, Streets of Desolation, was one of the greatest pieces of 8-bit music I'd ever heard. I was fond of it not just because it was aurally pleasing but also because it wonderfully evocative and had the power to emotionally connect me to the action. Its invigorating intro lifted my spirits and inspired me bravely charge forward into unknown territory, and its proceeding verses, which were somewhat melancholic in tone, caused me to enter into a reflective state and start wondering about the nature of the environments I was traversing--what their mood was like, what their darkly shaded constructions were trying to convey, and what type of habitants they were likely to invite.

The equally powerful (though nameless) Stage 2 theme, which provided accompaniment to the deadly chemical factory, was more upbeat in comparison (and amazingly rockin' in nature!), yet it, too, had that same underlying melancholic quality to it and thus the same ability to make me stop and think about the game's world and wonder why it was so cold and desolate. "What is it that's quietly haunting this place?" I attempted to discern. "And what could be the source of it?"

That was the way in which the game's opening stage themes immersed me. That was how enchanting they were.

The rest of the game's tunes were also very impactful, yes, but none of them were quite as powerful as Streets of Desolation and the unnamed Stage 2 theme, whose ability to evoke strong feelings and emotions and convey information was simply unmatched. Hell--sometimes I'd pop the game into the NES solely for the purpose of listening to these two themes and thinking about the story that they were telling me. They were that captivating.

What the soundtrack said to me, above all, was that Batman's world was a creature of its own design. It didn't belong to the movie. It was, rather, what it chose to be: purely the product of NES technology. That's was the music worked to establish. "The world that you're traversing is designed to lovingly embrace the NES' aural and visual values and communicate to you that this Batman property is married specifically to Nintendo's little gray box," it was eager to say.

And that message was certainly clear to me.

I liked everything about Batman's first stages. They served as a great introduction to the game and specifically to its world and its ideas.

Sadly, though, that's where my enjoyment of the game ended. Because that was the point in which SunSoft's designers began to rely upon one of the NES' more infamous values: extreme difficulty. In Stage 3, the level design, suddenly, began to turn so cruel and sadistic that I simply couldn't handle it; and consequently Batman was no longer the capable hero that he appeared to be in the opening stages.

And the following stages' even-heavier focus on precision only made the situation worse. It did even more to highlight the fact that Batman's jumping controls were diminishingly stiff and rigid and that he wasn't nearly as deft or as proficient as Ryu Hyabusa, who I couldn't help but compare him to.

The main problem was that you had a minimal amount of control over the movement of Batman's wall-jumps, and the result was that it was difficult to adjust on the fly and correct for mistakes. If you miscalculated a wall-jump, you were likely dead.

Batman's punching attack also had a troublesome element to it: a slight stall. So you had to press the attack button in advance if you wanted the punch to execute in time. The was forgivable in the early going, when the action was mostly grounded and the penalty for screwing up was the loss of but a mere single health unit, but not so much later on when you had to perfectly time and execute punches during segments in which it was necessary to take out higher-positioned flame-spewing enemies while performing series of do-or-die wall-jumps. In those types of segments, the punch attack's reliability would drop precipitously.

So instead, I was forced to rely on Batman's three secondary weapons (the batarang, the spear gun, and the three-directional dirk), which I didn't want to do because their ammunition was limited and I needed to save them for the bosses, against whom punch attacks were extremely risky (because you had to get real close to a boss if you wanted to punch it).

If I used my weapons, I'd remain in good health, but then I wouldn't have enough ammunition for the boss battle. But if I attempted to save my ammunition, I'd get abused in the climbing segments and arrive at the boss room with only two or three units of health.

Either way, I'd be in big trouble.

I mean, I'm not sayin' that I wasn't a skilled player, no. I was honestly very good at games. At that point in my life, I was able to beat some of the toughest action games around. It was just that I didn't know how to deal with Batman's particular brand of platforming challenges because I'd never before encountered anything like them.

What hindered me the most was the game's ever-increasing emphasis on wall-jumping. I wasn't able to master the move, and that was a problem because becoming proficient with it was a requisite. That's what I learned when I advanced to the game's middle stages, at which point the wall-jumping challenges started to become absolutely ridiculous. Sometimes they would require me to perform a crazy wraparound maneuver whose execution entailed dropping off a platform's edge; quickly turning inward, toward the wall; and then pressing the jump button at just the right time and with the exact amount of pressure needed to propel Batman over a four- or five-tile gap!

Executing this maneuver under normal conditions was tough enough, and it became exponentially more difficult to execute when it was the case that the surrounding structures were lined or filled with enemies, spikes, electrical currents, and deadly rotary devices. In such instances, you were required to execute the maneuver with pixel-perfect precision, and I simply wasn't able to do that with any consistency.

One of the level designer's favorite tricks was to line low-hanging ceilings with spikes and create challenges in which you had to execute long wall-jumps while somehow limiting your vertical movement. And these challenges routinely destroyed me. I couldn't execute the wall-jumps with the proper pressure-sensitivity, so I'd usually get too much verticality on my jumps and crash Batman's head into the spikes--even at times when I wasn't even close to touching the ceiling (one of Batman's flaws was its spotty hit-detection). So if a stage section was comprised of a series of such challenges, I'd be toast.

So that was the problem: Batman's stages dragged on forever, and they were filled with nasty wall-jumping challenges. And it was all too much for me.

The game was nice enough to let me continue from the area in which I died, yeah, but that didn't mean much when, in all likelihood, clearing the area in question required me to negotiate my way through a gauntlet of ten-twenty highly demanding wall-jumping challenges. All I could do in such instances was tank my way forward and hope that my health meter would hold out. And even if I was lucky enough to make it through, I'd be so low on health that I'd be no match for the stage's boss, which would no doubt overwhelm me with its supercharged projectiles and berserk dash attacks.

If I had an adequate amount of health, though, the boss wouldn't be a problem for me. I'd easily beat it in a damage race by spamming the batarang or the dirk.

The bosses, in general, weren't really that tough. I knew how to handle them.

But what I couldn't handle were those goddamned giant hoppy guys that started appearing in the third stage's earliest portion! Those orange hell beasts were the bane of my existence. They were like Big Eye from Mega Man except three-times quicker and completely unassailable. Whenever I'd devise a strategy for dealing with them, they'd immediate render it ineffective with their hyperactive, rapidly executed pouncing attacks.

No matter which weapon I was using, I couldn't make solid contact with the hoppers. They'd invariably evade the attack and then proceed to corner me and stomp me to death. And because they were so fast, I couldn't outrun them; they'd follow me to the area's endpoint, if the level design allowed for them to do so, and hound me every step of the way.

And while I was flailing away helplessly, hoping to land even a single blow on a hopper as it mercilessly pounced on me, all I could do was wonder about the mental condition of the person who designed the enemy. "How much of a deranged psychopath do you have to be to come up with an enemy like this?" I'd say aloud while waving my hand at the TV screen, in an exasperated fashion, and watching on as the same hopper frantically and savagely stomped me to death for the 20th time.

Because in moments like those, it once again obvious to me that some designers were absolute sadists who joined the industry only because they liked to mentally torture kids.

But I didn't give up on the game. I kept playing it and trying to progress. I felt that if I was able to improve my wall-jumping skills even moderately, I could endure the game's most difficult platforming segments and find a way to achieve ultimate victory.

Sadly, though, I eventually hit a wall. No matter how much I improved, I wasn't able to advance past the game's final area: the hellish gear tower! It was one of the most absurdly difficult platforming segments I'd ever seen in a game!

The wall-jumping challenges in this tower were all harrowing, and they required a type of extreme precision that was far beyond what I was able to exhibit on a consistent basis. I was almost driven mad by the repetitiveness of the exercise--by my constantly bumping Batman's head into the upper gears and falling into gear pits, by my repeatedly mistiming jumps, and by my endless failed attempts to reach the tower's top. It was a nightmare experience.

By some miracle, I made it to the final boss (or what I thought was the final boss) during one of my attempts, but I didn't even get the chance to land a shot on him. As soon as the battle commenced, he charged at me and promptly destroyed me. The defeat was so brutal and demoralizing that it forced me to question myself and seriously wonder if I had what it took to endure the gear segment and defeat the stage's monstrous boss (what was also weighing on me was my expectation that the Joker, too, was going to appear as a boss in this stage).

I wasn't sure that I did.

But still, I kept at it and tried as hard as I could to achieve ultimate victory.

I don't recall how many times I attempted to beat the game in the following weeks and months, but I know that each attempt ended in failure. It was the final gear segment. It got me every time. And ultimately, it was the reason why I quit playing the game. It became an object of fear for me, and I had no desire to ever subject myself to it again.

I was so scarred by my experiences with that segment, in fact, that I closed my mind to the idea of buying the game's sequel, Batman: Return of the Joker, and pretty much every other Batman game in existence. Because I was sure that each one of them would contain segments that were just like Stage 5's gear tower.

I didn't stay away from the game forever, of course. I returned to it about a year later, after I became a more-skillful player, and finally beat it. But I didn't return to it only because I wanted to beat it, no; I did so, also, because I enjoyed immersing myself in its enchantingly unique world and particularly in its first two stages, whose music, visuals and atmosphere combined to create one of the most wondrous, thought-provoking video-game settings I'd ever visited.

And 25 years later, I still revisit Batman for that same reason. I still return to it with the intent to admire and enjoy its strongly evocative visuals, music and atmosphere and the wondrous world they work to form.

I can't stress enough how much I appreciate what SunSoft did with Batman. The company could have taken the easy path and made some quick money by rushing to pump out a generically designed, bog-standard adaptation of Tim Burton's blockbuster film--by simply modifying a premade game and swapping in some Batman sprites--but instead it boldly endeavored to deliver to NES-owners a truly unique- and ambitious-feeling product.

And the result was a game that accomplished two remarkable feats: It succeeded in vigorously standing apart from its source material and establishing itself as an amazingly distinct, self-contained video game and a pure NES creation; and it earned the right to be counted among the console's best action games.

And that's how I'll always remember Batman--as a game that succeeded wildly in forging its own identity and consequently provided me entry into one of the most unforgettably wondrous video-game worlds I ever visited.

No comments:

Post a Comment